Repairing and Restoring Singapore’s Reel Heritage

The Asian Film Archive has been restoring old classics since 2014.

By Chew Tee Pao

Wong Kar Wai’s In the Mood for Love (2000). David Lean’s Lawrence of Arabia (1962). Charlie Chaplin’s Modern Times (1936). Satyajit Ray’s Pather Panchali (1955). These are just a handful of canonical works by the auteurs of world cinema that have been digitally restored in the last 10 years.

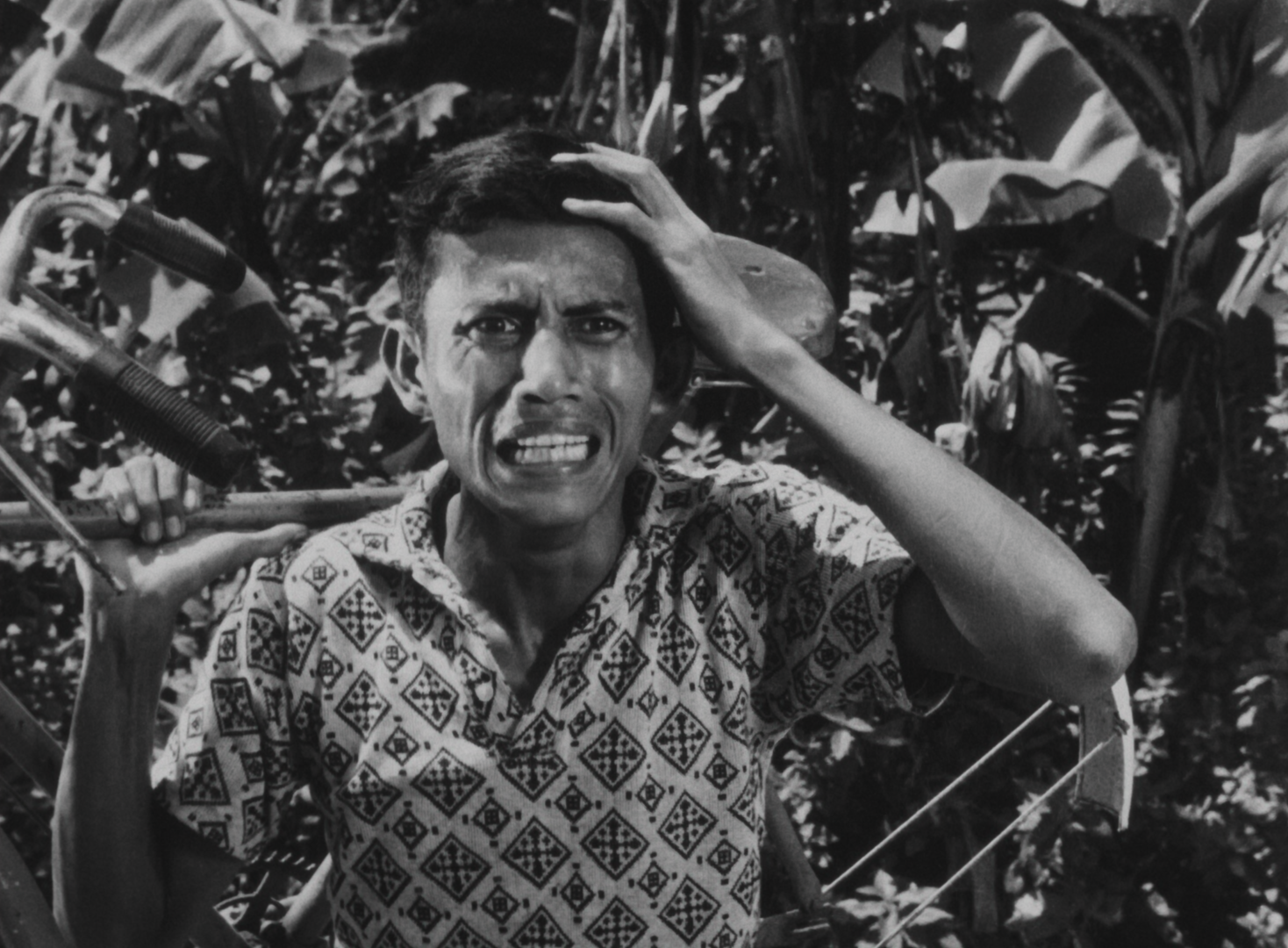

In 2012, the World Cinema Project and the National Museum of Singapore restored the Indonesian film Lewat Djam Malam (1954, Usmar Ismail). This project marked a major milestone for the restoration of Southeast Asian films with international support. In the ensuing years, films like Mee Pok Man (1995, Singapore), Manila in the Claws of Light (1982, Philippines), Mukhsin (2006, Malaysia), Tiga Dara (1957, Indonesia) and Santi-Vina (1954, Thailand) have been restored by both private and public archival institutions.

These movies were made using cellulose acetate-based film, a transparent plastic film used by photographers and filmmakers. The filmed materials were processed as picture and sound negatives that enabled copies of 35 mm theatrical prints to be produced for the cinemas.

However, film degrades over time. The condition of both cellulose nitrate and cellulose acetate material is highly dependent on temperature and relative humidity. Storing film materials at room temperature or warmer, and coupled with high humidity, will inevitably cause chemical decay in the base and emulsion of the film material.

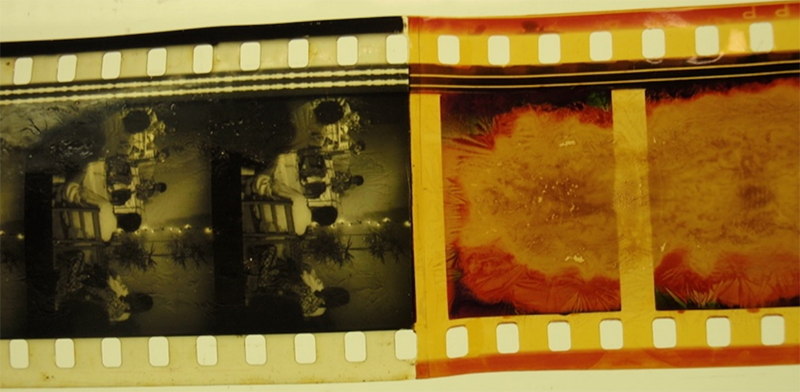

In Southeast Asia’s tropical climate, the degradation resulting in the colour, image and sound loss of the material can occur easily with the lethal combination of humidity and heat. Problems such as “vinegar syndrome” cause films to become brittle, shrink and emit an acidic odour. In addition, the warm environment is a perfect breeding ground for the growth of mould, mildew and fungus. Improper handling and transportation of the material have also resulted in mechanical damage such as torn splices and broken perforations.

Breathing New Life into Classic Films

For films that are in poor condition and at risk of being lost completely due to deterioration, restoration is the most immediate intervention to salvage the film.

While “preserved” and “restored” are often used interchangeably in stories about rereleased and restored classic films, the terms are not synonymous. Veteran film archivist Ray Edmondson describes preservation as “practices and procedures necessary to ensure continued access, with minimum loss of quality, to the visual or audio content or other essential attributes of the films. This includes surveillance, handling, storage environments and methods”.1

Film restoration, on the other hand, is a highly specialised process consisting of different stages that involves digitising, duplicating and reconstructing a specific version of a film by piecing together surviving source materials, and using digital restoration tools “to identify and thoughtfully remediate damage and deterioration suffered by the original material and to return the appearance of a film to a state closer to what it would have been when it was first created”.2

In Singapore, the work of restoring old films has been spearheaded by the Asian Film Archive, a subsidiary of the National Library Board. Formed in 2005 as a non-profit organisation to preserve the rich film heritage of Singaporean and Asian cinema, the AFA began restoring films in 2014 starting with two movies from the Cathay-Keris Malay Classics Collection, which is a collection of Singapore films dating from 1958 to 1973. This is the largest single film collection that is being preserved by the AFA.

The story begins in 2007 when 91 surviving film titles, with a total of 671 reels in 16 mm and 35 mm formats, were donated to the AFA by Cathay Organisation for preservation. Cathay-Keris Films and Shaw Brothers’ Malay Film Productions (MFP) were the main producers of Malay films during the 1950s to 1970s, a period that is usually referred to as the golden age of Malay cinema in Singapore.

Many of the films produced by Cathay-Keris (including productions under the banner of Keris Films) from 1953, which includes Buloh Perindu (1953, B.S. Rajhans) and Pontianak (1957, B.N. Rao), are considered lost. This makes the donated surviving film materials a rare and significant collection that highlights the evolution of filmmaking in Singapore, and its development as a film production and distribution centre.

These Cathay-Keris films portray the traditional mores and culture of the Malays and provide a visual documentation of the physical landscapes, nation building, economic challenges, rapid modernisation, religious and social changes that occurred in Singapore in the post-war era.

The 35 mm and 16 mm prints were stored in a warehouse when AFA first encountered them, and all the reels were affected with varying degrees of vinegar syndrome that had developed over the decades. The AFA took four years, until 2011, to complete the processing and hand-cleaning of all the reels.

In 2013, the AFA nominated the Cathay-Keris Malay Classics Collection to the UNESCO Memory of the World Committee for Asia and the Pacific (MOWCAP) to be inscribed on the Regional Register, a listing of endangered documentary heritage that represents a legacy for the world’s community. In 2014, the collection became AFA’s and Singapore’s first inscription on the MOWCAP Asia Pacific Regional Register. The inscription marked a significant milestone for the AFA and the collection, amplifying the value of the films, and highlighting AFA’s purpose to make the collection accessible through digitisation and restoration before further loss could happen.

Saving a Private Collection for the World

In 2014, the AFA began its restoration efforts of the Cathay-Keris films. Two works were identified: Sultan Mahmood Mangkat Dijulang (1961, K.M. Basker) and Gado Gado (1961, S. Roomai Noor). These were chosen because they were in the worst condition. Mould and chemical decay had affected the prints, resulting in severe warpage and shrinkage of the material.

Two sets of film elements were available for Sultan Mahmood Mangkat Dijulang. Reels 5, 8 and 11 of the 35 mm print were missing and had English subtitles burned in. Therefore, the 35 mm print was largely unusable and the film was mostly restored using the 16 mm print.

For Gado Gado, only the first reel of its negative had survived, but it was completely unusable due to serious decay, warping and shrinkage. The film was restored from a first generation 35 mm print.

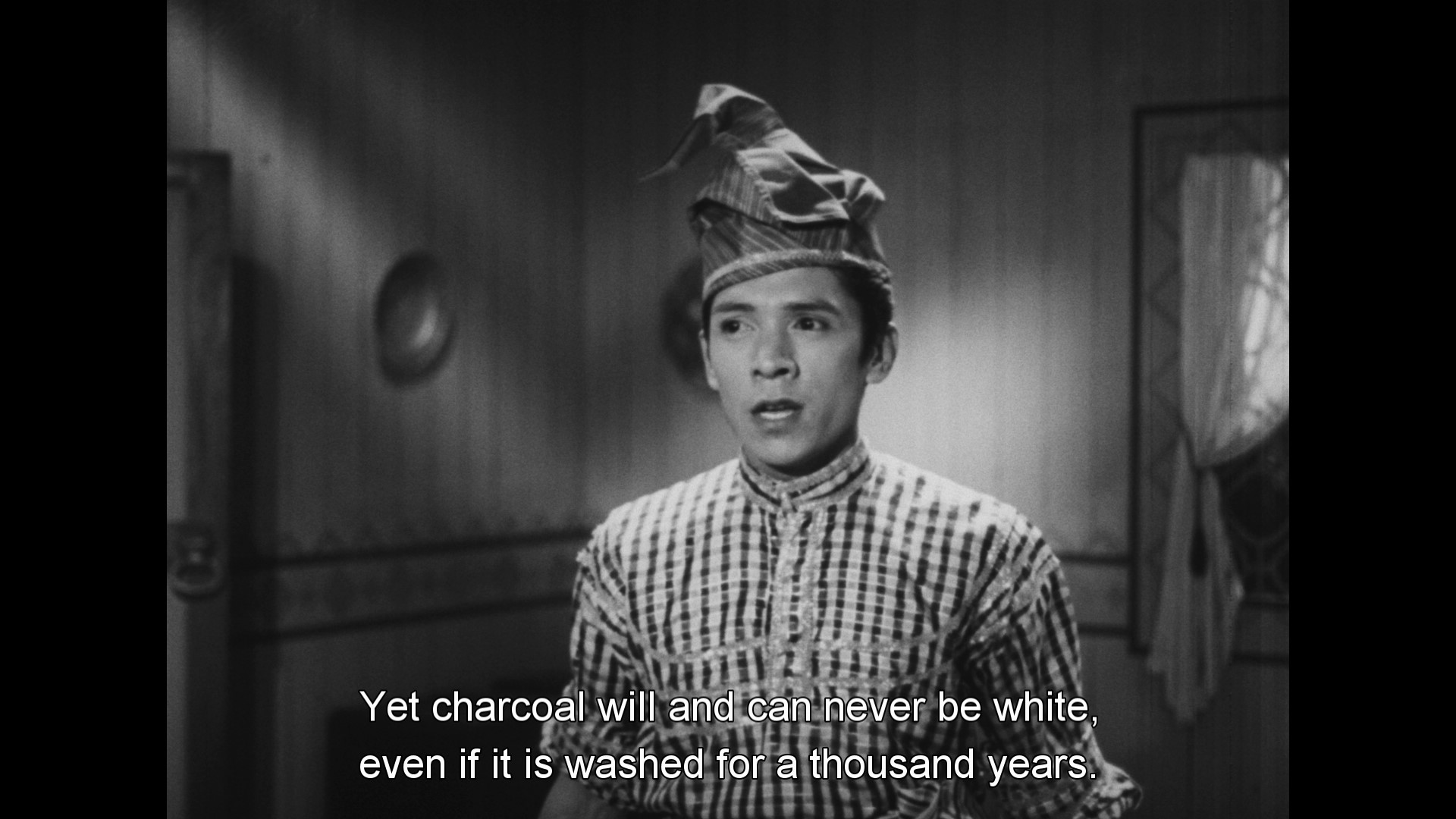

Both works were unique within the Cathay-Keris collection. Based on the 17th-century Malay Annals, Sultan Mahmood Mangkat Dijulang was one of the studio’s finest achievements among its stable of historical dramas and featured a rare star-studded cast.

The film was directed by K.M. Basker, an Indian filmmaker who was responsible for many of the early Malay films produced by both Cathay-Keris and Shaw Brothers’ MFP in the 1950s, before Malay directors took the reins. Gado Gado was a charming oddity for being the only medium-length musical variety film that featured a host of star actors, resembling a tribute to the studio’s stars.

The restoration of both films took over six months, and the restored films were presented for the first time with newly created English and French subtitles at the Cinémathèque Française as part of “Cinemas de Singapour en 50 films”. This was a special retrospective programme co-organised by the Singapore Film Commission that showcased 50 Singaporean films to commemorate the nation’s 50th year of independence in 2015.

Gado Gado was also selected for the Il Cinema Ritrovato, the first Singaporean work to be screened at an important film festival for heritage and restored films in the Italian city of Bologna. Sultan Mahmood Mangkat Dijulang made its Singapore premiere at the National Museum of Singapore Gallery Theatre in 2015 in celebration of AFA’s 10th anniversary and its first film restoration. To date, AFA has restored a total of nine titles from the surviving film elements of the Cathay-Keris Malay Classics Collection. The other seven are Chuchu Datok Merah (1963, M. Amin), Aku Mahu Hidup (1971, M. Amin), Orang Minyak (1958, L. Krishnan), Dang Anom (1962, Hussain Haniff), Chinta Kaseh Sayang (1965, Hussain Haniff), Mat Magic (1971, Mat Sentol and John Calvert) and Dara-Kula (1973, Mat Sentol).

Chuchu Datok Merah is a classic period drama by Malay director M. Amin that was restored and first presented in August 2015 at “Spotlight of Singapore Cinema” at the Capitol Theatre in celebration of Singapore’s 50th year of independence. M. Amin was Cathay-Keris’ most prolific director, having worked on nearly 30 films over a span of 10 years. He remained with the studio till the very end when it ceased operations in 1972.

One of the last films produced by Cathay-Keris is Aku Mahu Hidup. Written by Rajendra Gour, a pioneer of early independent short filmmaking in Singapore, the film’s adoption and sensitive treatment of the then controversial subject of prostitution portrays the progressive social consciousness of 1970s Malay cinema.

Cathay-Keris’ Orang Minyak, based on traditional folklore of a supernatural creature dripping in shiny black grease who abducts young women at night, predated Shaw Brothers’ MFP’s Sumpah Orang Minyak (1958, P. Ramlee) by a couple of weeks, demonstrating the competition between the two film studios for audiences. L. Krishnan was one of the first Indian directors employed to produce the earliest Malay films by Shaw Brothers and Cathay-Keris in the early 1950s.

Dang Anom and Chinta Kaseh Sayang are two of the 13 films directed by Cathay-Keris’ star director Hussein Haniff. Unfortunately, he had a short career and died at the age of 32. However, he is regarded today as an auteur of classic Malay Cinema.

In 2020, the AFA restored Mat Magic, the only title in the Cathay-Keris collection jointly directed by iconic comedian Mat Sentol, and the American magician and film actor John Calvert. It marked an early creative collaboration between Singapore and Hollywood, and was the concluding film of the Mat series produced by Cathay-Keris. The restored film made its world premiere at the 50th International Film Festival Rotterdam in 2021. In the same year, AFA also restored Dara-Kula, a horror film by Mat Sentol, illustrating his move away from the comedy genre for his last work during his time at Cathay-Keris.

Shaw Brothers’ Malay Film Productions

Unlike the Cathay-Keris Malay Classics Collection that the AFA has been preserving since 2007, very few titles from Shaw Brothers’ MFP have survived on film.

The first MFP film that the AFA encountered was a surviving 16 mm print of Patah Hati (1952, K.M. Basker), which starred a young P. Ramlee in one of his first major roles. The print was critically affected with mould and vinegar syndrome. It was discovered in the collection of the National Museum of Singapore during the search for MFP titles to restore and present at the “Spotlight on Singapore Cinema” event in 2015.

Upon close inspection, the first several minutes of the film were found to be completely missing from the print. The findings signified that the film was at potential risk of being lost in its entirety if nothing was done, thus giving greater reason to salvage and restore whatever remained of the material.

Patah Hati was one of the most challenging film restorations ever encountered by experienced restorers at the Italian laboratory L’Immagine Ritrovata, who carried out the restoration in 2015. The substantial number of missing image and audio frames, and extensive wear and tear meant that many individual frames needed to be carefully repaired before scanning was even possible, adding many man-hours to the task. The severe scratches and mould defects on the print required additional processing during the digital restoration stage.

After six months of hard work, Patah Hati was finally restored and presented at “Spotlight on Singapore Cinema” in 2015. A text slate was included at the start of the film to address the entire missing first scene and to explain the challenges of the restoration.

Singapore’s Only Known Surviving Nitrate-based Film

In the course of restoring Patah Hati, the AFA stumbled upon a surviving 35 mm film print of Permata Di-Perlimbahan (1952, Haji Mahadi), produced by Shaw Brothers’ MFP and kept in the collection of Shaw Organisation. It is the first Singapore film directed by a Malay director. Made at the beginning of the studio era, the film features one of the earliest film performances of Maria Menado and Nordin Ahmad for MFP before they moved to Cathay-Keris in the mid-1950s. Prior to this, Malay films were directed by Chinese and Indian filmmakers. What is even more fascinating is that the film is currently the only known extant Singapore film in a cellulose nitrate-based print.

The nitrate film format is chemically unstable thus making it highly flammable, and it is usually kept under sub-zero and underground storage. That the print stayed intact in Singapore’s hot and inhospitable environment for decades is a miracle.

After the film was handed to the National Museum of Singapore, the print was sent to the specialised care of L’Immagine Ritrovata in 2014. AFA only discovered that it was a nitrate print when L’Immagine Ritrovata presented their findings.

By that time, the print was already in an advanced state of chemical decay and shrinkage, affected by mould and numerous stains. Months of different chemical and rehydration treatments were carried out by the restorer to help alleviate the effects of nitrate decay on the image and in the sound. Continuous scratches and tears were present on every reel, which required intensive manual reconstruction for parts of many frames.

When combusted, nitrate film has a high burning point, is virtually inextinguishable and can spread quickly. Therefore, it needs to be stored in a low-humidity and protective environment, with temperatures below freezing point. It also needs to be kept away from other films. With no dedicated facility in Singapore that can handle and store nitrate films, the 35 mm print is now in the care and custody of Cineteca di Bologna’s nitrate film vault (a film archive founded in 1962 in Bologna).

The restoration of Permata Di-Perlimbahan took almost a year to complete before it was presented at AFA’s annual film and art event, “State of Motion 2020: Rushes of Time”.

The Fate of P. Ramlee’s Seniman Bujang Lapok

The first Malay classic film that I encountered when I started work at AFA was Seniman Bujang Lapok (1961) by the Malay film icon P. Ramlee. A self-referential spoof of the Malay film industry of the late 1950s to early 1960s, the film never fails to make audiences young and old laugh. The film exists today in video format and on poor quality VCD and DVD releases.

In 2017, the AFA discovered that the surviving print had been left with L’Immagine Ritrovata by the National Museum of Singapore in 2014. We looked into the feasibility of restoring the print, but the vinegar syndrome and degradation of the prints had already reached a fatal and unsalvageable stage.

Of the seven 35 mm reels, only the last reel could be salvaged. It took 10 weeks, using two different chemical treatments, to be able to uncoil the sticky reel. A large portion of the images had disintegrated and without additional sources of film elements, the film could not be restored.

The eventual digitisation of the last eight minutes, despite the hissing and shaking staticky images, provide a glimpse of how this beloved film could have looked and sounded on the big screen. The loss of this gem highlights the urgency of preserving what we can of our cinematic heritage while it is still possible.

Before the start of any film restoration, we need to assess the appropriateness of the film materials on hand to ascertain if the “best” surviving source materials are complete and available. A single print may not represent the best surviving source material. Extensive research is carried out to determine if other sources of restorable film materials exist and are residing outside one’s own holdings.

Film Inspection and Identification

Film identification is the single most important way to date a film material and identify its technical characteristics. Information such as film type/gauge, manufacturing codes, length, and general condition are recorded to help the restorer make informed decisions on actions to be taken and to document any changes in the film’s condition from the time it was acquired to when it is next inspected.

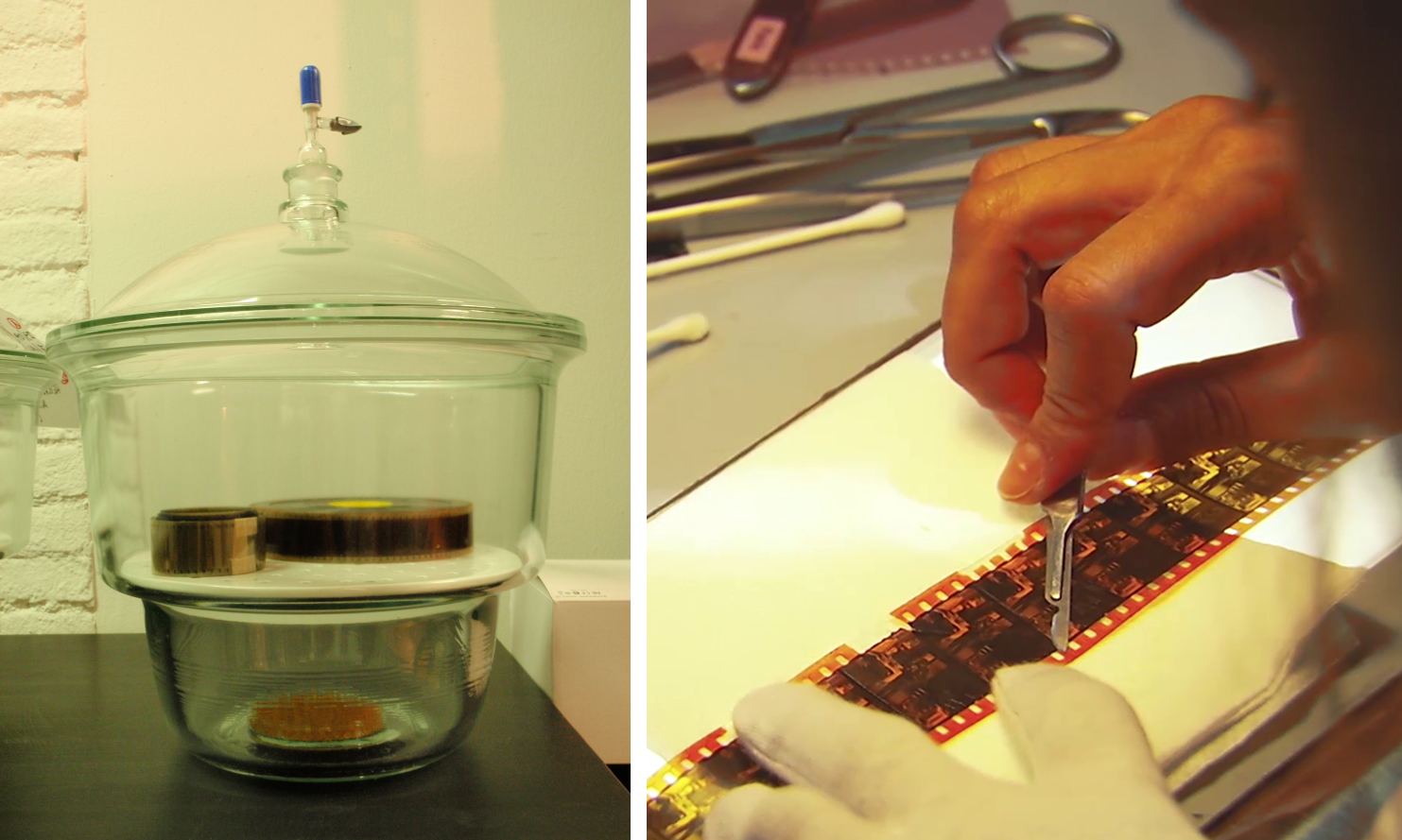

Film Repair

After inspection, the film element will need to be repaired to ensure it can withstand any mechanical cleaning and digitisation processes. Broken splices/perforations are manually mended and strengthened, and visible residue from tape adhesive removed.

Film Cleaning

Cleaning is essential to remove mould and projection oil from the film before digitisation can take place. Besides manual cleaning, the restorer may also utilise ultrasonic cleaning equipment with high-frequency, high-intensity sound waves in a liquid to facilitate and enhance the removal of foreign contaminants from the material’s surfaces at different speeds. This is all dependent on the condition of the material. The film is then air-blown to dry it completely before it can be scanned.

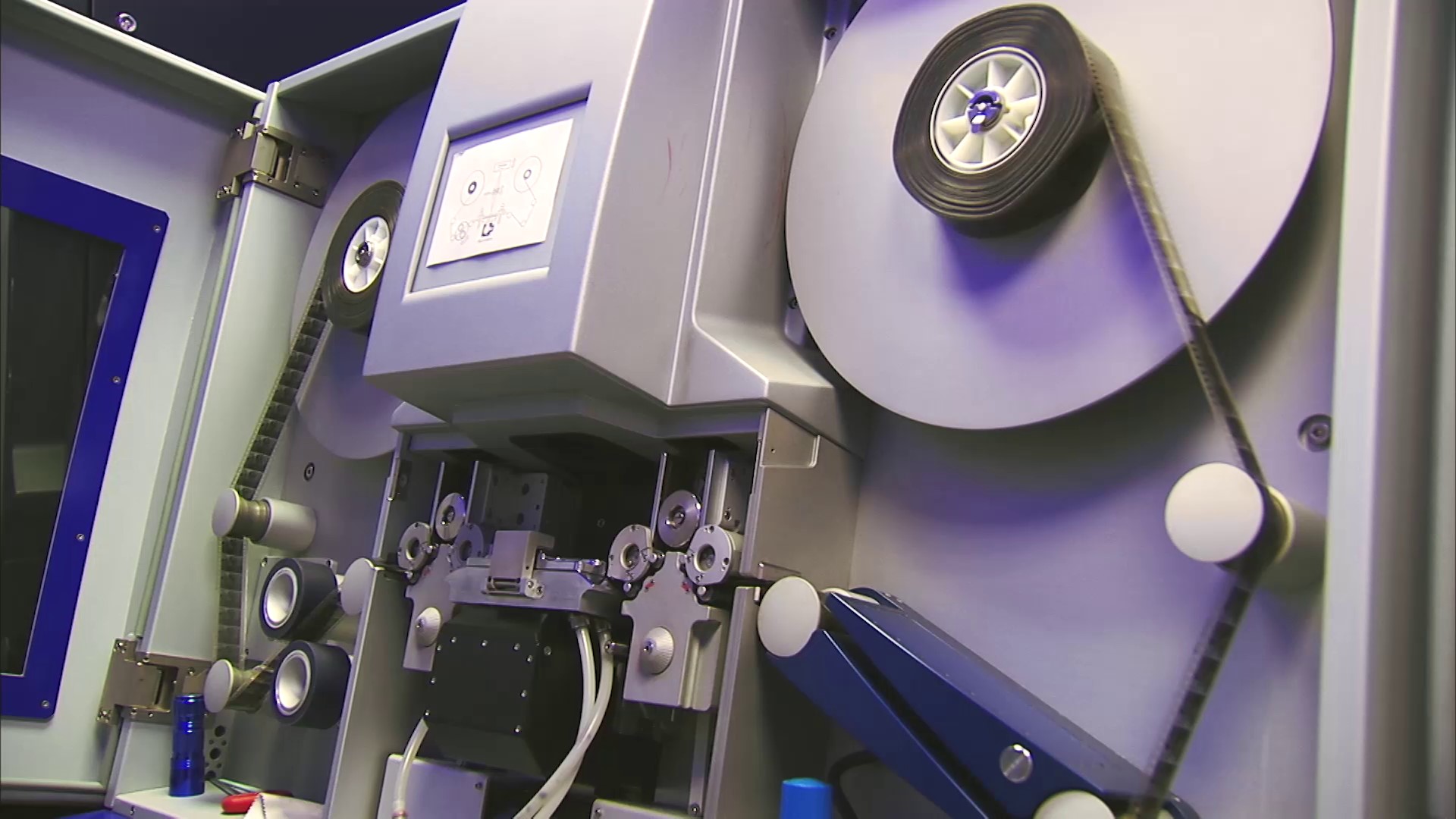

Film Scanning

Film scanning is a process that captures each frame of film with its own digital file. The standard for motion pictures is 24 frames per second and each frame of film would have a corresponding Digital Picture Exchange (DPX) image file. A 90-minute film would have approximately 129,600 of these high-resolution digital scans, which would then be ingested and assembled using the restoration software.

Film Comparison

No two sets of film elements, even from the same title, are the same. This is because the condition of the elements would vary. This is why the film comparison stage is crucial, especially when there is more than one source material known to exist. The aim in comparing different sets of film elements is to be able to select and piece together the definitive version of the film using the best possible image and sound from all available source materials.

Digital Image Restoration

The most labour-intensive component of film restoration involves using a combination of manual and automated digital tools to de-flicker, de-warp, remove dirt and scratches, stabilise images, as well as reconstruct missing and damaged frames.

Sound Restoration

The audio tracks on a film element are digitised separately using a dedicated sound capturing device. Audio restoration software is used to eliminate or reduce clicks, crackles, and bumps, smoothen excessive noise and balance the overall tone for a better auditory experience. The sound restoration process happens concurrently with the image restoration, and the restored audio will eventually get synchronised with the restored image.

Colour Correction

Colour correction is a process that is necessary to recover the original tone and colour of the film due to colour fade that could also affect the contrast and exposure levels of the image. This is necessary even for black-and-white films since there are gradations of black and white tones.

Subtitling

Translation and subtitling are vital components of restoration for the contemporary circulation and exhibition of classic films, especially when the film contains any foreign language that might impede the general viewer experience.

Film Mastering

With the restored and colour corrected scans, the restorer can generate the output as a variety of digital files and formats suited for purposes such as theatrical screenings, streaming as well as publishing.

Digital Asset Management

From the restoration, digital files and formats are generated and saved for different purposes. In AFA, hard drives are used to access the restored materials, and Linear Tape-Open (LTO), a form of data cartridge formatted for long term digital storage, is used for preservation.

Print and Processing

While the variety of digital files and formats generated from the restoration would facilitate and provide access to the film/s through contemporary platforms, it is necessary to consider the continued long-term preservation of the film. Printing the restored work back onto analogue film that include new picture and sound negatives and keeping it in archival storage has proven to be a more stable preservation solution than solely preserving the digital content.

That said, developing new negatives and prints is a costly and intricate process that is not always done, as issues such as the project budget and physical storage space would have to be considered.

Heritage institutions, including archives like the Asian Film Archive (AFA), leverage the visibility of restoring significant film titles to advocate for a variety of causes. For the AFA, restorations are the means to raising awareness of the importance of film preservation, and the urgency to care for the original and/or surviving film elements that make the restorations possible. As film restoration is a costly endeavour, the preservation condition, the rarity of the film materials, and the cultural and historical meaning that the restored work would bring to audiences, are curatorial considerations that AFA makes in selecting film/s to be restored.

Chew Tee Pao has been with the Asian Film Archive (AFA) since 2009. As an archivist since 2014, he has overseen the restoration of over 30 films from the AFA collection.

Chew Tee Pao has been with the Asian Film Archive (AFA) since 2009. As an archivist since 2014, he has overseen the restoration of over 30 films from the AFA collection.NOTES

-

Ray Edmondson, “The Building Blocks of Film Archiving,” Journal of Film Preservation 24, no. 50 (March 1995): 55–58. (From ProQuest via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

Robert Byrne, Caroline Fournier, Anne Gant and Ulrich Ruedel, “The Digital Statement Part III: Image Restoration, Manipulation, Treatment, and Ethics,” International Federation of Film Archives, accessed 7 November 2022, https://www.fiafnet.org/pages/E-Resources/Digital-Statement-part-III.html. ↩