“Book City” in Two Streets: The Chinese Bookstore Scene in Postwar Singapore

Some Chinese bookstores in Singapore have managed to survive despite the challenges of the digital age and the decline in Chinese readers.

By Lee Ching Seng

In the last two decades, the successive closure of numerous Chinese bookstores in Singapore have drawn laments from book lovers. Bookstores have always been an integral part of my life. Since I was a child, I have loved visiting bookstores to buy books and peruse the colourful stationery on display. As an adult, I once even owned a bookstore and also worked as a librarian for more than 40 years. During this time, I had the opportunity to meet many book lovers and bookstore operators. The fact that bookstores are now becoming a sunset industry is, for me, a bitter pill to swallow.

Book Streets: North and South Bridge Roads (1950–70)

My love affair with Chinese bookstores in Singapore began in 1966 when I first arrived here from Malaysia for my undergraduate studies at Nanyang University (Nantah). Back then, I lived in a dormitory on campus. Most Singaporean students who stayed in the dormitories would go home on weekends or during the holidays, so Malaysian students would be left behind and the campus would be unusually quiet. To stave off loneliness, my fellow Malaysians and I would go downtown to watch movies or visit the bookstores.

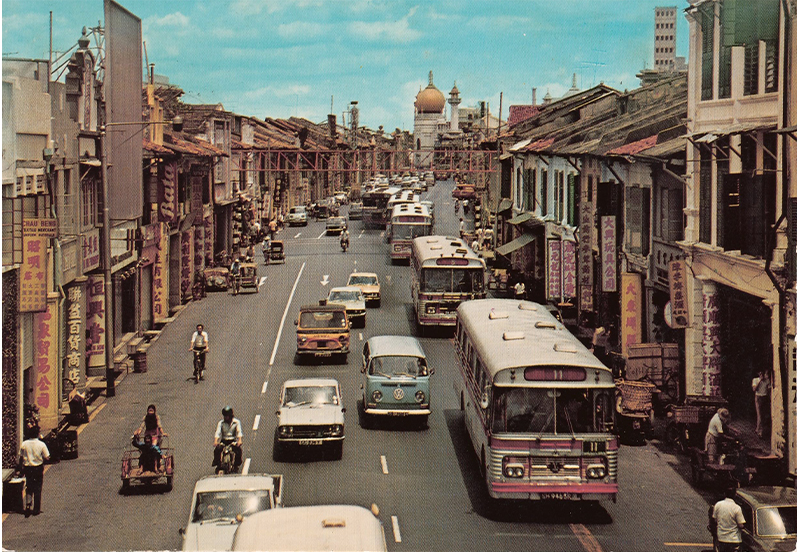

In those days, buses travelling from Nantah to town would end their journey at the terminal station on Queen Street, in the Bugis area. This was also where unlicensed taxis from Nantah would end up as well. There were between 20 and 30 bookstores clustered on North Bridge Road, Victoria Street, Middle Road, Bras Basah Road, Queen Street, Waterloo Street, Bencoolen Street, Prinsep Street and Selegie Street, as well as countless small book stalls nestled along the five-footway of shophouses.

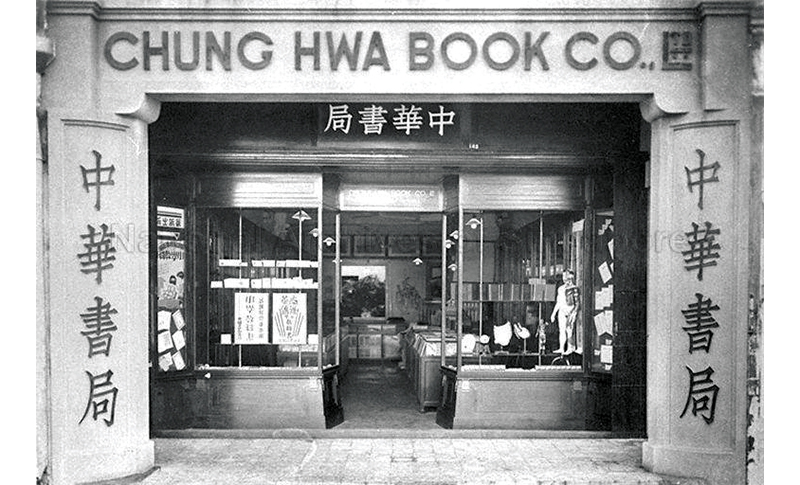

The most well-known were Chung Hwa Book Company (中华), The Commercial Press (商务), Union Book Company (友联), Popular Bookstore (大众), Youth Book Company (青年), The Nanyang Book Company (南洋), China (中国), Black Cat Book Co. (黑猫) and The Student Book Store (学生). They were all situated along North Bridge Road or in one of its alleys. On nearby Victoria Street were other books stores like Shanghai Book Company (上海), Tah Lian Book Store (大联) and Sing Lien Book Store (星联).

The concentration of bookstores in the North Bridge Road area helped to develop a vibrant reading culture. Each bookstore distributed or published its own unique genre of books and appealed to different categories of customers who thronged the stores on weekends. In the 1950s and 1960s, when public libraries had yet to become commonplace, these bookstores were havens for young people with intellectual inclinations.

Bookstores such as Shanghai, Chung Hwa, Popular, Youth and Student – which distributed publications from mainland China and Hong Kong, as well as periodicals from Singapore and Malaysia – were popular among left-wing readers, including secondary school students, college students, young working adults, science students from Nantah, and young people interested in literature and the arts. Occasionally, in some of the smaller bookstores, one could even find publications from China that the government had banned from importing.

Back then, I used to frequent Union on North Bridge Road. As the bookstore stocked the most comprehensive range of books from Taiwan, it was also referred to as the “Taiwan book specialist”. Most of the reference books recommended by professors of the Nantah College of Arts could be found in Union. On the other hand, students who studied Malay would visit Shanghai Book Company to buy Chinese-Malay dictionaries, Malay language magazines and bilingual books in Chinese and Malay.

After I was done visiting the bookstores on North Bridge Road, I would walk, or take a bus to South Bridge Road, the heart of the other book street. Spanning Upper Cross Street, Cross Street, South Bridge Road and New Bridge Road, South Bridge Road had the highest concentration of Chinese bookstores before World War II.

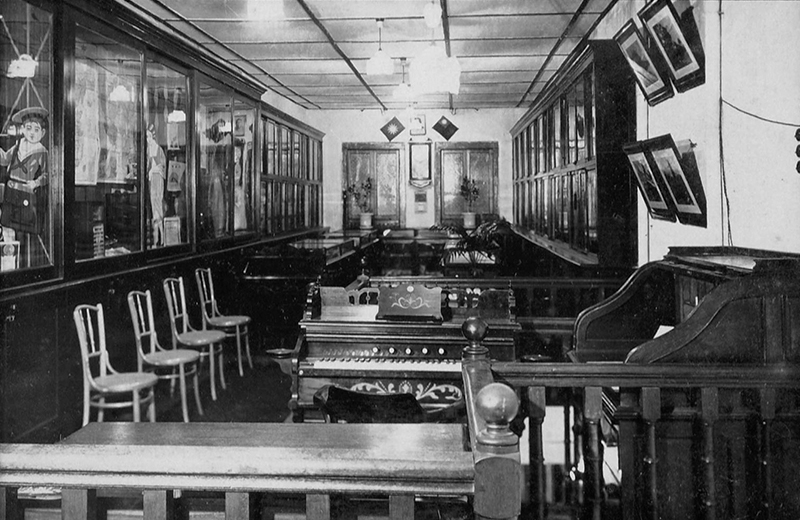

In the prewar era, most local Chinese bookstores also sold stationery and sporting goods. About 22 of these stores were of considerable scale. After the war, the nucleus of the book street, formerly centred on South Bridge Road, moved to North Bridge Road. By this time, only two bookstores, The World Book Company (世界) and a branch of Chung Hwa Book Company (中华), remained on South Bridge Road. Pan Shou, the famous Singaporean poet and calligrapher, often did his calligraphy work on the second floor of Chung Hwa on weekends. These public demonstrations of his art drew a great number of calligraphy lovers, who visited the store to ask for his autographed works.

Book Cities: Golden Mile and Bras Basah (1970–80)

After Singapore gained independence in 1965, urban redevelopment took place at breakneck speed. Many old shophouses along North and South Bridge roads were demolished, and gleaming skyscrapers took their place. The majority of these high-rise buildings housed shopping malls, offices and residential units. New towns such as Queenstown, Toa Payoh and Ang Mo Kio sprang up in less densely populated suburban and rural areas.

In the 20 years that followed, the evolving urban landscape also brought about further changes: both the North Bridge Road and South Bridge Road book scenes shrank. One by one, Chinese bookstores moved into modern shopping malls that came with better facilities but had high rental rates.

In the 1970s, I was working for the National Library, and visiting bookstores to buy books was part of my job. If my memory serves me, when the Golden Mile Complex on Beach Road opened in 1973, the first batch of tenants included seven Chinese bookstores: Vanguard Book Room (前卫), Wan Li Book Co. (万里), Soon Seng Book Store (顺城), Bailien Bookstore (白莲), Yuancheng Wenhua Book Company (源城), Heng Lee Book Store (兴利奕) and Rinian Bookstore (日年). In 1979, these bookstores held their first joint sale, which attracted many book lovers. Later on, more Chinese bookstores moved into Golden Mile Complex. These included The House of Literature (文学), Fengyun Publisher (风云), Dong Sheng Publisher (东升), and several others, bringing the total number of bookstores in the complex to nearly 15.

The success of the bookstores at Golden Mile attracted even more independent bookstores to commercial buildings in the vicinity of Beach Road, including Textile Centre at Jalan Sultan (home to Grassroots Book Room [草根书室], Sang Yang Book Store [向阳] and Yuan Yuan Book Store [源源]) and Shaw Centre (home to Xinghai Bookstore [星海]and Crystal Book Room [翡翠]). These two centres, together with Golden Mile Complex, formed a bookstore cluster that attracted bibliophiles.

In 1978, the Housing and Development Board built Bras Basah Complex, a mixed-use development housing both commercial and residential units on North Bridge Road to accommodate bookstores and other shops in the downtown area. Bras Basah Complex, also known affectionately as the City of Books in Chinese (书城), officially opened in 1980.

Besides being home to older and more established English and Chinese bookstores from the North Bridge Road area such as Popular, Shanghai, Union and Youth, Bras Basah Complex also attracted newer bookstores like Xinhua, Books and Arts of All Ages (今古), Seng Yew Book Store (胜友), International Books (国际), Maha Yu Yi (友谊) and Evernew Book Store (永新) to set up shop on its premises. Within a short time, the new complex had replaced Golden Mile as the heart of the Chinese bookstore industry in Singapore.

The City of Books subsequently drew older bookstores like Commercial Press and independent bookstores such as Grassroots and Great River Book Company (长河) to either set up branches or new stores there. As a result, North Bridge Road has, once again, become the centre of the local Chinese bookstore scene, and its position remains unchallenged even to this day.

Conglomerate Bookstores (1980–99)

Bras Basah Complex is currently the largest book hub in Singapore. It comprises 117 units (including office space), with more than 90 of these occupied by bookstores or stationery shops. Among the many bookstores there, Popular’s flagship store is the biggest. Covering an area of around 2,323 sq m and spanning three floors at the time, it was considered the largest bookstore in Southeast Asia when it opened in 1980.

Popular was founded by Chou Sing Chu, who had come from Shanghai and set up The World Book Company in Singapore. The first Popular store was located at 205 North Bridge Road. In the 1980s, just as the Chinese bookstore industry started to go downhill, Popular became one of the first bookstores to take up a lease at Bras Basah Complex. It transformed into a bilingual bookstore selling both Chinese and English books. It also pioneered a new business model by selling stationery and gifts on a large scale. This was a refreshing change in the traditional Chinese bookstore trade.

In 1994, the Chou family merged The World Book Company and its subsidiaries into Popular, making it the first conglomerate bookstore in Singapore. Today, Popular Holdings operates in Hong Kong and various countries in Southeast Asia. With more than 4,000 publications and nearly 40 publishing houses under its belt, Popular offers literary books, periodicals, Malay dictionaries, textbooks, teaching aids and more. These publications are distributed through its network of publishing houses in Singapore, Jakarta and Hong Kong.

Another bilingual conglomerate bookstore that grew from humble beginnings in Singapore to becoming a global player was Page One (叶一堂). In 1983, the company opened its first store in Parkway Parade, along Marine Parade Road, far away from the City of Books at North Bridge Road. During Page One’s early days, the store specialised in design and art publications, making it one of the earliest specialty bookstores in Singapore. At one point, Page One even had bookstores in China, Taiwan, Hong Kong and Thailand.

Struggling to Stay Afloat (2000–22)

However, by the 2000s, the Chinese bookstore industry began its decline as online bookstores entered the scene. The death knell for local Chinese bookstores sounded with the changes in buying and reading preferences brought about by the rise of these digital bookstores and the rapidly shrinking Chinese-reading population, coupled with increasing operating costs. Even as physical bookstores transformed into conglomerates, adopted a bilingual approach, or created niche markets, they were no match for the emerging e-book industry and its digital sales strategies.

The decline was keenly felt in 2011 when numerous bookstores went out of business or closed their stores in Singapore. These included the American book and music retailer Borders, which shuttered both outlets in Singapore, Chinese bookstores Shanghai and Vista Culture Square (远景), and specialty bookstores such as Page One. Popular Holdings, listed on the main board of Singapore Exchange in 1997, was delisted in 2015. It was evident that a strategy of conglomeration, bilingualism and diversification was ineffective in reversing the fortunes of the floundering Chinese bookstore industry.

However, some smaller Chinese bookstores known for their customer-centric and unique approaches – such as Union, Xinhua, Maha Yu Yi and Wanchun Book Store (万春) – managed to survive the competitive climate and are still in business today. Although these bookstores do not carry English titles, they have, somewhat miraculously, retained their share of the Chinese book market.

Union, which used to specialise in books from Taiwan and Hong Kong, has undergone a transformation under the leadership of Managing Director Margaret Ma. Today, Union sells books from China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Singapore and Malaysia written in both traditional and simplified Chinese. At the same time, the bookstore works with primary and secondary schools and libraries to promote new books, and also acts as a middleman to purchase books from overseas publishers on behalf of schools and libraries. The bookstore celebrated its 70th anniversary in June 2022 (for more information about Union, check out the article in the Oct–Dec 2022 issue of BiblioAsia).

Grassroots Book Room is another example of a small bookstore that was able to pivot successfully, though not easily. The late Yeng Pway Ngon, who later became an acclaimed writer and Cultural Medallion recipient, founded the bookstore in Textile Centre in 1976 but it closed in 1981. In 1995, Yeng re-established the store on North Bridge Road, but after two decades of struggles, he sold the business in 2014 to former journalist Lim Jen Erh, arts lover Lim Yeong Shin and medical doctor Lim Wooi Tee. The bookstore has since relocated to Bukit Pasoh Road, where it continues to serve book lovers today.

Tan Waln Ching, a former employee of Grassroots, founded City Book Room (城市书坊) as a home publishing business in 2014. Two years later, it moved to North Bridge Centre, a few units away from Grassroots’s original location. In June 2022, City Book Room relocated once more, this time to Joo Chiat Road in the east.

Both Grassroots and City have successfully carved niches for themselves. They have created cultural spaces for readers and authors to come together in the celebration and promotion of new books. By organising events such as talks, themed book fairs and recitals, they also provide opportunities for authors and readers to interact with one another and share their love of books and reading.

A New Lease of Life

It is thanks to dedicated book lovers, who have been quietly pushing back against the declining trend of Chinese bookstores, that Singapore can still boast of the stores mentioned above. Despite the scarcity of Chinese bookstores in Singapore today, these brick-and-mortar stores are each unique in their own ways. Together, they safeguard a literary niche in the compressed space of the city we call home, prioritising cultural legacy over profits.

For readers, these bookstores provide sustenance for the soul; for writers, they provide a platform for the publication of their books; for creative youths, they offer a nurturing space for imaginative pursuits; and for the next generation, they provide a conducive environment that encourages Chinese reading.

Even though Chinese readership in Singapore is declining and the golden age of Chinese bookstores has passed, I believe that the worst is over. Moving forward, these independent bookstores – with their personalised touches and new business models – will give the bookstore industry a new lease of life.

Lee Ching Seng is former head of the Chinese Library at the National University of Singapore. As a subject specialist in Singapore and Southeast Asian collections and resources, he has written bibliographies on Singapore Chinese literature, and articles on library collections and the overseas Chinese in Singapore and Southeast Asia.

Lee Ching Seng is former head of the Chinese Library at the National University of Singapore. As a subject specialist in Singapore and Southeast Asian collections and resources, he has written bibliographies on Singapore Chinese literature, and articles on library collections and the overseas Chinese in Singapore and Southeast Asia.