The Origin Stories of Keramat Kusu

Pilgrimages to the keramat on Kusu Island have been going on since the mid-19th century.

By William L. Gibson

In April 2022, a catastrophic fire engulfed the keramat (shrine) on the top of a hill on Kusu Island, off the southern coast of Singapore. Media coverage of the event showed the near-total destruction of the keramat.1

The keramat on Kusu Island is a popular pilgrimage spot with thousands of devotees making their way by boat to seek blessings from the shrine as well as the Chinese Tua Pek Kong Temple (龟屿大伯公宫) on the island. Despite its immense popularity, little is definitively known about the shrine. Delving into the records shows how the origin story of the keramat has changed over time.

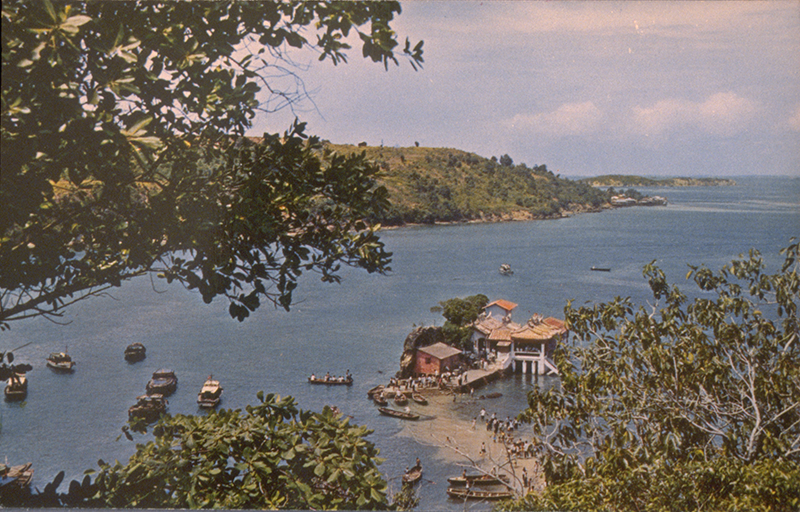

Sunny Kusu Island – little more than a dome-shaped granite outcropping connected by a mud flat to a narrow rocky protrusion to the north, and surrounded by shallow reefs – was both an important navigation mark as well as a shipping hazard in the days of sail.

Around 1822, the British erected a signal on the island and as a result, the earliest maps of Singapore refer to it as “Signal Island”. The island was later renamed “Peak Island” and sometime in 1877, a brick obelisk harbour marker was erected on its south shore.2

The Malay name for the island is Pulau Tembakul, which means “mudskipper island”, either because mudskippers were once abundant on the mud flats or because in profile the island, with its bulbous head and narrow fin-like tail, resembles a mudskipper. “Kusu”, which means “turtle” in Hokkien, likely comes from the dome shape of the island resembling a turtle shell.

Shrines and Temple

Remarkably, there is evidence that the Tua Pek Kong Temple and the keramat have been on the island since at least the mid-19th century.3 This is based on a letter written by Cheang Hong Lim, a prosperous opium trader and head of the Hokkien community in Singapore, to J.F.A. McNair, Colonial Engineer and Surveyor General of the Straits Settlements, on 9 March 1875. Cheang protested the policy of using the island as a burial ground for the quarantine facility located on nearby St John’s Island.4

In the letter, Cheang petitioned for a title to the island. He wrote that the island had “for upwards of thirty years [c.1845] been used by many of the Chinese and native inhabitants of this Settlement as a place for them to resort to at certain periods every year for the purpose of making sacrifices and paying their vows to certain deities there called ‘Twa Pek Kong Koosoo’ and ‘Datok Kramat’, and as that place has lately, to the great prejudice of their feelings, been desecrated by the interment therein of a number of dead bodies”.5 In the end, Cheng did not receive the land title but he did get a promise that quarantine burials would cease.

Datuk keramat (sometimes spelled as dato) are spirits who dwell within natural objects like trees, rocks, termite mounds and whirlpools. Also known as datuk kong (拿督公), these ancestor spirits of the landscape are often represented by icons that resemble older Malay men. (Datuk is the Malay word for grandfather and is also a generalised honorific for an elder male, while kong is the Hokkien word for grandfather.)

Cheang’s letter refers to the practice of people visiting the temple and shrine on Kusu. The island was – and still is – thronged by pilgrims for the Double Ninth, or Chongyang Festival (observed on the ninth day of the ninth lunar month), during which it is customary to venerate graves of ancestors and to climb a high mountain.6 It is likely that the rocky peak of the island jutting out of the water was a place to perform Chongyang rituals: both Tua Pek Kong (literally “Grand Uncle”, a deity unique to Malaya) and a local datuk spirit of the island would be treated as ancestors to be propitiated. (It is not unusual to find Tua Pek Kong temples and datuk keramat shrines close to one another.7)

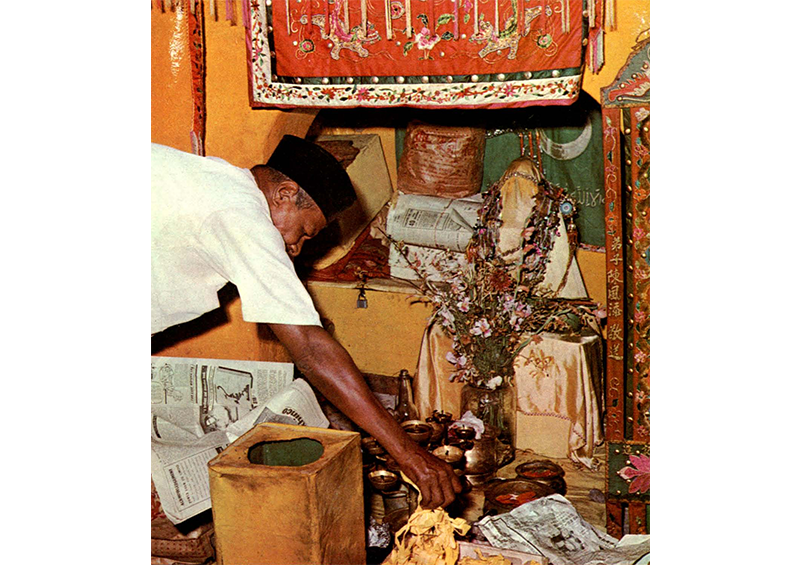

The keramat was especially popular with couples seeking to have children and for prognosticating winning lottery numbers and it received visitors year-round.

More early details about the pilgrims who visited Kusu come courtesy of a report dated 16 October 1894 in the Baba Malay newspaper Bintang Timor. It reads: “Smalam dan hari Anam, banyak umbok umbok, baba baba dan orang Melayu dan segala bangsa ada pergi Koosoo bayar niat. Dia orang kata ini kramat ada banyak betol, dan dia slalu kasi apa dia orang minta.”8 [“Yesterday and on Saturday, many Peranakan women (umbok) and men (baba), Malays and people of all races went to Kusu to offer niat (supplication). People say that the keramat is honest and true and will give you what you ask for.”]

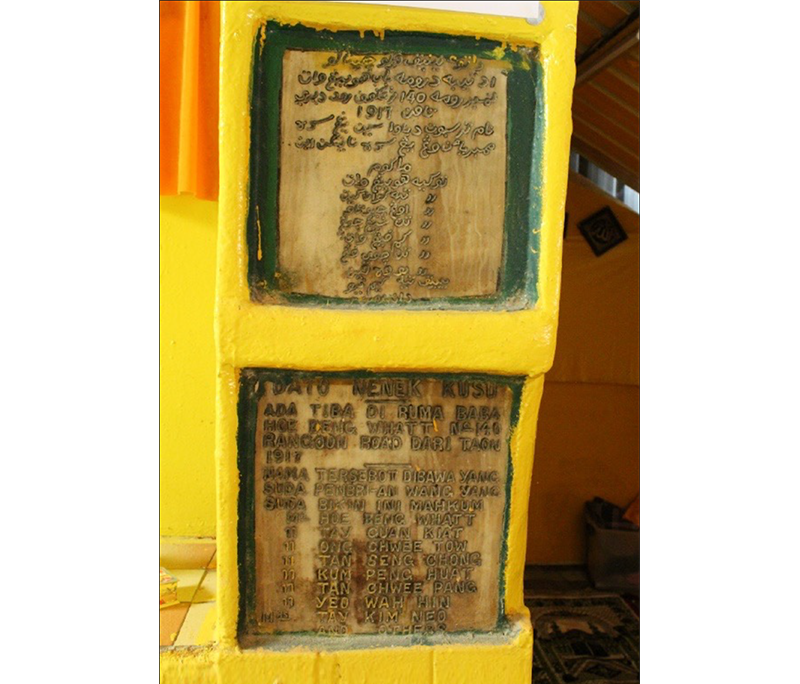

The keramat was enlarged in the early 20th century. There are two plaques on the site, one in Baba Malay and Jawi dated 1917 and the other in Hokkien Chinese dated 1921. The Baba Malay plaque is dedicated to “Dato Nenek Kusu” and was emplaced by Baba Hoe Beng Whatt, a Peranakan (Straits Chinese). It includes a list of Baba Chinese who donated money to erect the shrine. The 1921 plaque also bears the names of donors to the shrines, many of whom were the same people who had donated earlier. The text on the plaque mentions that the “old fairy of Kusu Island” (龟屿老仙女) visited Hoe’s house with a child. The second plaque indicates that the shrine was expanded again in 1921.

Fishermen’s Friends

A Straits Times report in 1929 offers one of the oldest descriptions of the origins of the keramat. The reporter spoke to an old man at Joo Chiat (the implication being he was Baba or Straits Chinese), who gave an account that deserves to be retold in detail:

“Years and years ago there was a hilly spot, opposite the Police Station at Tanjong Pagar [Bain Hill, where another keramat, that of Syed Yasin, was located]. The coolies who were employed to level this hill more often than not had to pay with their lives. Many of them died after doing a day’s work. Those who were responsible for the work then resorted to the use of dynamite to break up the hill, and on the same night it happened that a sampan took across four or five Arabs in the direction of Kusu. Before the sampan man had actually arrived at the island, to his great amazement he found that his passengers had disappeared. He took the hint that they were the gods of this hilly spot who were removing to Kusu, and said nothing of the news until a few days after.

“In the meantime, the sampan man became rich and prosperous, being well-compensated for his trouble. This news was favorably received by the people, and pilgrimage to the place commenced. A Malay man who heard of it went to the island and led a hermit’s life until he died there. A Chinese who thought that such an island should have a temple erected one, so that those who visit may worship its gods.”9

A lengthy article about Kusu in a 1932 Straits Times report introduced new elements to the story. It noted that some time in the “olden days”, a Chinese fisherman who felt unwell was put ashore and, “in accordance with his dying wishes”, was buried on the deserted island by his friends who also erected a tombstone for him. Not long after, a Malay fisherman died on the island was also buried there. Friends of the two fishermen became rich after dreaming about the deceased fishermen and began paying their respects to the spirits.10 This version of the story forms the basis for the “legendary” version of Kusu Island that most of us are familiar with today in which the two men become sworn brothers.11

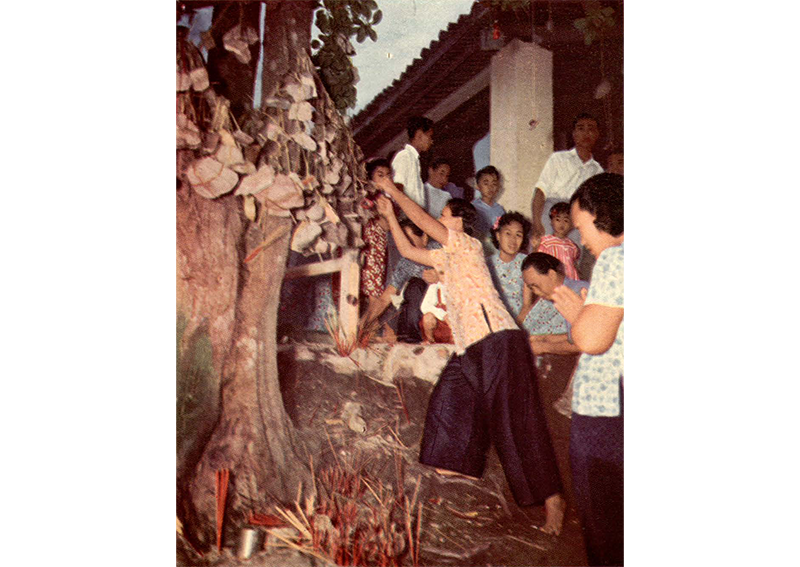

In the early days, the keramat was not associated with any particular named individual. The 1932 article describes the shrine as two small “sheds” of concrete. “One covers the grave of the Malay fisherman. The other is also supposed to be the graves of other Malays but no stories, so far as I can gather, are told concerning them.” The article adds that on a nearby keramat tree, “strings of stones” were hung. “When a man has his wish fulfilled, he recalls his vow, goes back to the island, hangs up the stones and takes them down only when he has discharged his debt!”12 The hanging of stones was once common at other keramat in Singapore renown for powers of granting children, such as Iskandar Shah and Habib Nuh. While the tradition is no longer continued at these keramat, yellow ribbons are still tied on the trees around the keramat at Kusu.

Keramat Stories

By 1940, the Malay fisherman at the keramat had been transformed into a family, though still anonymous. A Singapore Free Press article in 1940 reports that the shrine was supposedly “built over the graves of two Malay girls whose father is also buried nearby”. The reporter who visited the shrine saw “one or two Malays up here but they were surrounded by Straits-born Chinese women in bright sarongs, and many young girls in flowered blouses and trousers”. She spotted a woman seeking lottery numbers and several more seeking sons. “There are many stones suspended from the old gnarled trunk, and the women who paid homage there were given little scraps of yellow cotton and flower petals wrapped in newspaper to take away with them to ‘bring them luck’.”13

The name associated with the keramat today, Dato Syed Abdul Rahman, first appears in a 1948 Straits Times article. It mentions that the shrine of the dato consists of a “spiral-shaped tombstone, covered by a wooden shanty” that was joined to a “smaller hut containing the similar tombstones of two of the Dato’s female ancestors, Naik Ralip and Siti Fatimah” (his mother and his sister respectively). A caretaker named Chik bin Embee, who claimed to be a direct descendant of the dato, cared for the tomb with his two sons and daughter.14

In 1952, an article in the Straits Times Annual notes that the dato was “supposed to have had miraculous powers and to have died well over a hundred years ago”. The article mentions that only a few Muslims would visit the keramat as it was “not a shrine that is popularly accepted and revered among the Malays. Its fame depends almost entirely upon reverence among the non-Muslim Chinese”. Chinese visitors would show respect to the dato by abstaining from pork for the entire ninth lunar month and that the “usual Chinese divining blocks” would not be used at the keramat. However, occasionally “a Chinese woman can be seen tossing a couple of coins surreptitiously to obtain the desired effect”.15

A 1973 article in Asia Magazine adds a new, important twist to the origin story, based on an interview with the then caretaker of the shrines, Pak Besar. The man told the magazine’s reporter a variation of the tale of the Malay and Chinese fishermen that 140 years before, “two ascetics, an Arab named Syed Rahman and a Chinese named Yam”, travelled to Kusu to meditate. “The two hermits paid other visits to the island, and then died on it”, although Pak Besar, insisted they were still spiritually alive. “They just left the world,” he said. Later, the body of the Arab’s mother, Ghalib, and his daughter, Sharifah Fatimah, were brought there for burial and shrines were erected over their graves.16

Ghalib is an Arabic name usually used for men; the mother’s name on Kusu is perhaps an echo of the Malay ghaib, which means “something hidden or unseen”. The earlier spelling of Naik Ralip is likely a transliteration of Nek Ghalib from an oral source, suggesting the names were not written on the tombs. The sister of the dato had also become his daughter instead.

Photographs from this period show the formerly white-washed walls painted dark green – a traditional keramat color. Only later were they painted bright yellow, the colour of datuk kong shrines in Singapore (in Peninsular Malaysia, they are often red).

In the 1970s, Kusu, along with the other Southern Islands, came under the management of the Sentosa Development Corporation which had been set up, as the name implies, to develop what was then Pulau Blakang Mati and adjacent islands into the resort destination of Sentosa.

Land reclamation enlarged Kusu from 1.2 hectares (12,000 sq m) to 8.5 hectares (85,000 sq m) at a cost of around $3.9 million. The development work included the construction of a new jetty, water supply system, modern toilet facilities and footpaths. The keramat and temple were preserved as tourist attractions, and major renovation works carried out at both in 1976 included concreting and adding guardrails to the steps up to the keramat.17 The new changes may have altered the original shape of the island, but they proved popular with visitors.18

A 1979 New Nation article reports a visit to the “Kramat Datuk Khong” that commemorates a pious man, Haji Syed Abdul Rahman together with his wife (rather than mother) Nenek Ghalib, and daughter, Sharifah Fatimah. The three of them, all “living in the days of Raffles” had climbed the hill and simply vanished without a trace, possibly by supernatural means. Syed Abdul Rahman’s “kinsmen were later advised in dreams to build a shrine for the three departed ones”. Visitors to the shrine were women seeking children and “numbers to instant fortune”, and the tradition of tying stones to the trees continued.19

Photographs from this period also show that other than cosmetic changes, the shrine looked much as it did until the fire in 2022.

Fire and Reconstruction

The pilgrimages to Kusu continued unabated over the decades and a routine had been established. Pilgrims would first visit the Tua Pek Kong Temple to seek blessings, before climbing the steps to the keramat on the top of the hill. There are several waypoints within the keramat, and numbers have been printed and pasted at the different spots so that devotees would know the order in which to visit the different stations.

The blaze on 17 April 2022, however, threatened to put an end to the rituals. The fire broke out on a Sunday evening, at about 6.20 pm, and was eventually put out by firefighters after about an hour, aided by heavy rain. While no lives were lost, the keramat was almost completely destroyed. The fire’s cause was not determined, but lit candles and incense are often left unattended there.

A month after the conflagration, it was announced that the keramat would be rebuilt at a cost of hundreds of thousands of dollars, in time for the Double Ninth Festival.20 In early September 2022, the Straits Times quoted the shrine’s caretaker, Ishak Samsudin, as saying that the keramat was about 70 percent rebuilt by then, and would “likely be ready” in time for the pilgrimage season at the end of September. Ishak told the newspaper that he had financed the reconstruction with donations from friends and companies.21

I returned to the site in November 2022. It had been rebuilt in time for the Ninth Month celebrations, but it was still not complete. A temporary marquee had been erected to provide shade and burned debris still littered the hillside beneath the shrines. The shrines were reconstructed in almost exact replicas with some of the original material, such as the concrete altars, left intact.

Unfortunately, the 1917 dedication plaques were badly damaged and poorly restored. However, by burning off decades worth of accumulated jerry-built material, the catastrophe revealed previously hidden artefacts. At the back of the altars for the two women are stone mounds commonly seen in datuk nature shrines. More intriguingly, a worn batu nisan (gravestone) placed before one of these mounds is inscribed with a Jawi phrase that mirrors the 1917 plaque. The phrase “Datuk Nenek” is legible, which suggests that a shrine-grave was erected here during the 1917–1921 renovations in honour of the female datuk of Kusu Island. During my visit, several worshippers passed through, marking their devotion with prayers and incense as the sea glittered below.

Dr William L. Gibson is an author and researcher based in Southeast Asia since 2005. His research topic for the Lee Kong Chian Research Fellowship, awarded by the National Library Board in 2021, was an in-depth study of keramat in Singapore. His book Alfred Raquez and the French Experience of the Far East, 1898–1906 (2021) is published by Routledge as part of its Studies in the Modern History of Asia series. Gibson’s articles have appeared in Signal to Noise, PopMatters.com, The Mekong Review, Archipel, History and Anthropology, the Bulletin de l’École française d’Extrême-Orient and BiblioAsia, among others.

Dr William L. Gibson is an author and researcher based in Southeast Asia since 2005. His research topic for the Lee Kong Chian Research Fellowship, awarded by the National Library Board in 2021, was an in-depth study of keramat in Singapore. His book Alfred Raquez and the French Experience of the Far East, 1898–1906 (2021) is published by Routledge as part of its Studies in the Modern History of Asia series. Gibson’s articles have appeared in Signal to Noise, PopMatters.com, The Mekong Review, Archipel, History and Anthropology, the Bulletin de l’École française d’Extrême-Orient and BiblioAsia, among others.NOTES

-

Kok Yufeng, “Loud Explosion Heard as Fire Breaks Out Near Malay Shrines on Kusu Island Hilltop,” Straits Times, 18 April 2022, https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/loud-explosion-heard-as-fire-breaks-out-near-malay-shrines-on-kusu-island-hilltop; Ng Wei Kai, “Firefighters Had to Scale 152 Steps and Link 18 Lengths of Hoses to Fight Kusu Island Fire,” Straits Times, 3 May 2022, https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/firefighters-had-to-scale-152-steps-and-link-18-lengths-of-hoses-to-fight-kusu-island-fire. ↩

-

“Variorum,” Singapore Daily Times, 30 June 1877, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

E.H., “The Cemetery,” Straits Times Overland Journal, 19 November 1873, 6. See also “The Straits Observer,” Straits Observer (Singapore), 25 March 1875, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Wednesday, 11th August,” Straits Times, 14 August 1875, 2. (From NewspaperSG). See also Song Ong Siang, One Hundred Years’ History of the Chinese in Singapore (London: Murray, 1923), 179. (From BookSG) ↩

-

For one version of the origin tale, see Jiqieng Juan, Festival: Chinese Folklore Culture Series (ISD LLC: 2017), 91–99. ↩

-

Jack Chia Meng-Tat, “Who Is Tua Pek Kong? The Cult of Grand Uncle in Malaysia and Singapore,” Archiv Orientální 85, no. 3 (2017): 437–60. (From ProQuest via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

“Bageimana Orang Dapat Perkerja’an Di Bawah Government China,” Bintang Timor, 16 October 1894, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“The Pilgrimage to Kusu Island,” Straits Times, 1 November 1929, 12. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Chinese Topics in Malaya,” Straits Times, 20 October 1932, 19. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

See, for example, Catherine G.S. Lim, Legendary Tales of Singapore (Singapore: AsiaPac Books, 2020). (From National Library, Singapore, call no. YRSING 398.2095957 LIM) ↩

-

Mary Heathcott, “Chinese Go to Pray and Picnic on Kusu Island” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 21 October 1940, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Sit Yin Fong, “Two Faiths Share Holy Island,” Straits Times, 24 October 1948, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

A.J. Anthony, “A Picnic… With the Harbour Gods,” Straits Times Annual, 1 January 1952, 26–27. (From NewspaperSG). The article also states that the keramat bore the date 1889. This date was not evident when I visited the shrine and does not accord with the information provided by Song Ong Siang that the keramat was active prior to 1875. Remarkably, an article published in the Straits Times Annual in 1970 under the same title repeated nearly verbatim the text from the 1952 article, though this time under a different author’s name – Goh Tuck Chiang. ↩

-

“Singapore’s Kusu Island,” Asia Magazine (16 September 1973), 18–19. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RUR q950.05 AM) ↩

-

Jack Chia Meng-Tat, “Managing the Tortoise Island: Tua Peh Kong Temple, Pilgrimage, and Social Change in Pulau Kusu, 1965–2007,” New Zealand Journal of Asian Studies 11, no. 2 (December 2009): 72–95, https://www.nzasia.org.nz/uploads/1/3/2/1/132180707/jas_dec2009_chia.pdf. ↩

-

Sentosa Development Corporation (Singapore), Annual Report 1976 (Singapore: Sentosa Development Corporation, 1977), 11 (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RLCOS 354.5957092 SDCAR); Sentosa Development Corporation (Singapore), Annual Report 1977 (Singapore: Sentosa Development Corporation, 1978), 14. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RLCOS 354.5957092 SDCAR) ↩

-

Francis Chin, “Kusu’s Little Kramat,” New Nation, 4 November 1979, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

李思邈 Li Simiao, “Gui yu na du gong miao xiufu kunnan duo shehui duofang fen shen chu yuanshou,” 龟屿拿督公庙修复困难多 社会多方纷伸出援手 [There are many difficulties in the restoration of the Dato Kong Temple on Kusu], 联合早报 Lianhe Zaobao, 16 May 2022, https://www.zaobao.com.sg/news/singapore/story20220516-1273019. ↩

-

Ng Wei Kai, “Shrines Destroyed in Kusu Island Fire 70% Reconstructed: Caretaker,” Straits Times, 5 September 2022, https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/shrines-destroyed-in-kusu-island-fire-70-reconstructed-caretaker. ↩