From Verdant Grounds to a Whole New Town: Reflections on Serangoon – A Place Like No Other

Assistant Curator at the National Museum of Singapore Daniel Tham shares more about the exhibition “Serangoon: A Place Like No Other” held at the newly opened Serangoon Public Library.

The history of modern Singapore has been marked by relentless change to its geographical and social landscape. From its establishment as a port settlement under colonial rule to its post-independence emergence as a global metropolitan city, the ongoing processes of urban development and transnational migration have unceasingly reconfigured the island’s boundaries, economy and culture. This has been most evident in the growth and development not only of the town centre, but also the changing functions and character of surrounding localities and estates around the island.

The story of one such estate – Serangoon – presents a microcosm of this broader narrative of Singapore’s historical trajectory, as traced in the exhibition “Serangoon: A Place Like No Other” at the newly opened Serangoon Public Library. Situated in nex, a shopping centre that is touted as the largest in the northeast of Singapore, this library finds itself at the heart of Serangoon’s latest transformation. Fittingly, the opening exhibition charts the historical journey of the neighbourhood the library was moving into, drawing out the multifaceted changes that have taken place in Serangoon since its beginnings in the mid-19th century, using a combination of archival research, oral history accounts, interviews and community contributions.

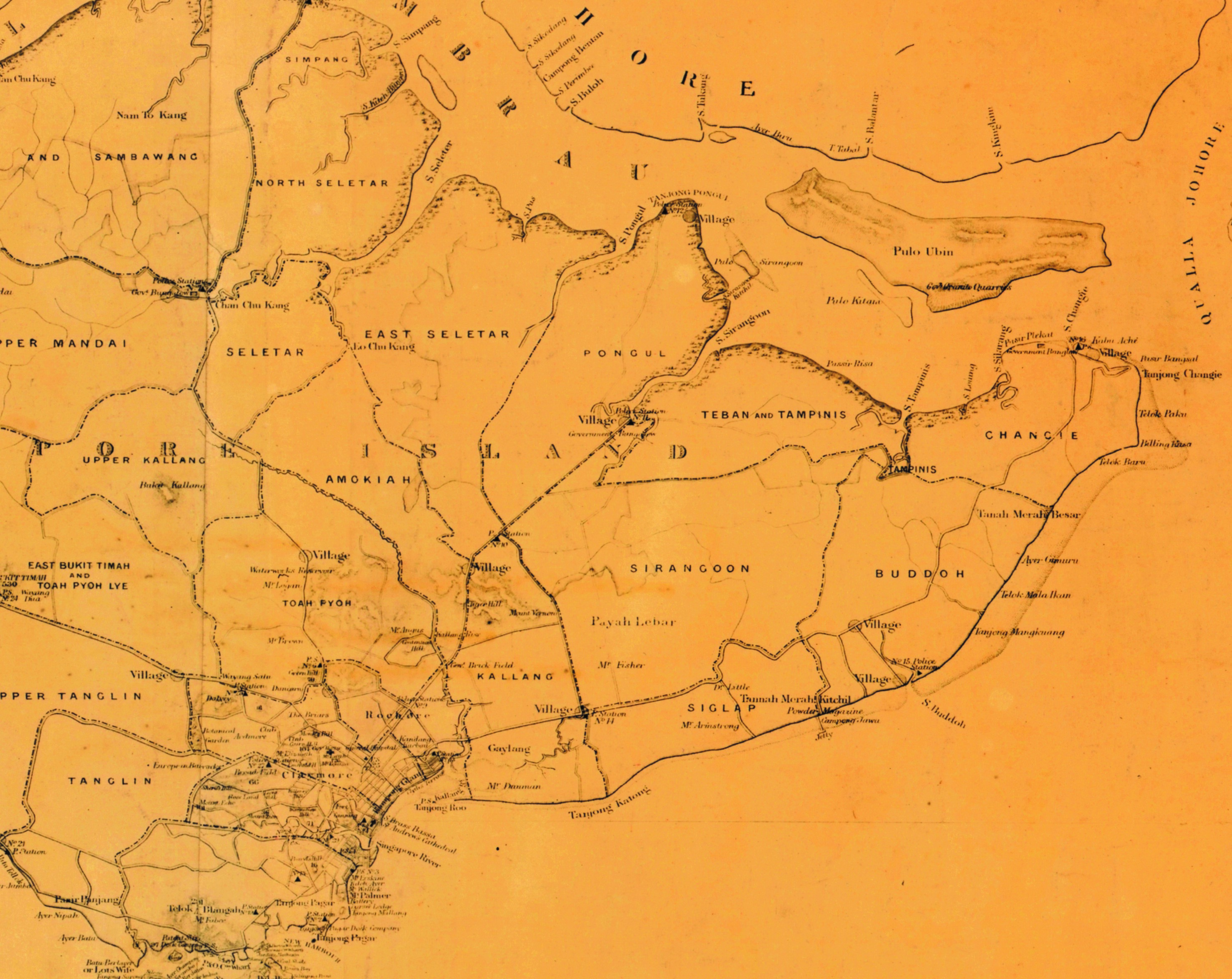

As it becomes clearer through the exhibition’s focus on what life used to be like in the area, the story of Serangoon is presented as one that intertwines with Singapore’s own transformation. With its fertile soil and plentiful land, Serangoon became a favoured location for fruit and spice plantations, and later at the turn of the century, rubber estates. While Singapore never really succeeded agriculturally, it was nonetheless the site of countless experiments on the commercial viability of various crops, with rural Serangoon being an early preference as a site among opportunistic cultivators.

Significantly, the common historical narrative of Singapore’s post-independence development, especially the rapid industrialisation of its workforce, is mirrored in the exhibition’s depiction of the transformation of Serangoon from its verdant grounds to a new town and urban centre. The emphasis on such a contrast is exemplified in the use of background photographs on each panel, alternating between images of old Serangoon and those of its present landscape, the latter depicting the estate at the height of urban progress in commerce and communication.

However, as the exhibition title aptly suggests, the emphasis of this historical excursion into Serangoon’s transformation lies more in asserting the estate’s distinctiveness and unique identity. This is achieved by uncovering curiosities such as the nomenclature of road names like Lorong Ong Lye and Lorong Lew Lian – referring respectively to pineapples and durians as part of the estate’s legacy of fruit-planting – and pointing out the estate’s connection with famous personalities like rubber merchant Ee Teow Leng and “Bee Hoon King” Lim Ah Pin, both of whom have roads named after them.

To demonstrate the formation and evolution of a unique Serangoon identity, much attention is given to the cultural domains of food and popular entertainment. Through the active contributions of long-time residents, familiar old haunts like Punggol Point and Paramount Theatre are fondly recollected and reminisced, along with current enduring favourites like Chomp Chomp Food Centre, built in 1972 to house hawkers in the area. Here, the geographical and cultural distinctiveness of Serangoon is represented through the subjective lived experiences of individuals and their shared memory as a community.

This reliance on nostalgic recollections facilitates the writing of the history of Serangoon from the ground up, with the lively individual accounts of residents presented in rich ethnographic tones. Anecdotes involving topics as disparate as gangster activities, crocodile hunting and glass-stringed kite fighting serve not only as candid or even quirky accounts, but also as precious and meaningful records of collective memory. This is supplanted with a home video montage of filmed everyday scenes of Serangoon Gardens in the 1960s, compiled from the contribution of a former resident, David Donnelly, whose family was among the many families of British and Australian servicemen based in Singapore and Malaya living in Serangoon Gardens.

Viewed as a whole, these oral and visual records allude nostalgically to a life that was once communal, spontaneous and carefree. Such a romanticisation of the past operates subtly as a critique of the constraints and rigidity of modern living, arguably the inevitable consequences of social change. One is reminded, in addition, of the various ways of life that have been left behind inadvertently as a result of progress. This includes vanishing trades like farming, fishing, boat repairing and ceramics production, and charmingly obsolete practices like the door-to-door personalised services rendered by food hawkers and confectioners.

This critique is counterbalanced, though, by reminders of the many conveniences of modernity. As the exhibition points out, with the opening of the North East Line in 2003, Serangoon residents now benefit from a mere 15-minute train ride to town. Similarly, with the development of its infrastructure and modern amenities, Serangoon may well be considered a self-sufficient residential estate. As such, the romantic longing for the old kampong life in Serangoon is held in constant tension with the many comforts of modern living its residents enjoy today.

The use of individual accounts in this exhibition also allows for the contestation of history itself, one example being the origins of Ang Sali (Hokkien for “red zinc”) as Serangoon’s unofficial nickname. Commonly believed to be named after a red zinc-roofed building at the junction of Yio Chu Kang Road and Serangoon Garden Way, this conventional version is challenged by one resident who offers his own alternative interpretation. As this exhibition highlights, history written from below is necessarily messy and never clear-cut, evident also in the contested views regarding the exact boundaries that delineate Serangoon’s location.

Although “Serangoon: A Place Like No Other” clearly relies on nostalgia as the immediate means of engaging its audience, it does venture beyond nostalgia in presenting the case for the estate’s unique historical significance. As a rural plantation area during the Japanese Occupation, Serangoon was notable as a place of refuge from the Japanese, who did not have a strong presence there. As it grew as a residential estate, it became well known for its high concentration of schools. Its historical landmarks are also well noted, ranging from the surviving Japanese Cemetery Park, established in 1891, to the former Alkaff Gardens, which opened to the public in 1929.

Whether as a mirror to Singapore’s own development, or as a unique estate with its own historical and cultural identity, Serangoon is celebrated in this exhibition as a neighbourhood that embraces diversity. This is most pronounced in the exhibition’s concluding sections, which pay tribute to the ethnic and religious diversity contained within the estate, as well as the harmonious relationships shared by its different communities. Yet, because these multicultural ties are presented as rooted in the communal lifestyle of old Serangoon, the accounts of these cross-cultural relations do raise the question of whether and how ties will bind in the context of increasing individualisation, a typical phenomenon of modern living.

An answer to that difficult question may perhaps be found in this exhibition itself, particularly the research process behind it. As the exhibition’s curator Tan Chui Hua shares, one of the most striking aspects of the various residents’ accounts is their diversity, with each account telling a different story strung together by the common experience of living in Serangoon. Because of the limitations of space, the excerpts selected for this exhibition offer only a glimpse of the plethora of perspectives and experiences offered by each resident.

Yet, it is the process of collecting, sharing and retelling these stories, and the celebration of their diversity in contributing to the estate’s unique identity, that may be most integral to maintaining existing relations and fostering new ones. Just as the larger question of Singapore’s national identity continues to rest upon how multiple layers of multiculturalism may be connected amidst a background of economic and social change, the evolving identity of Serangoon, as this exhibition suggests, will continue to be formed and transformed by the willingness of its residents today to engage with and build upon their distinctive heritage.

Assistant Curator

Curation & Collections

National Museum of Singapore