Oneness in Many: National Resilience in Singapore

The Singapore government has long championed and sought to inculcate resilience in its population. Associate Professor Bilveer Singh affirms the continued vital importance of this strength in adversity for the city-state’s survival.

Vulnerable states, big or small, are largely successful because of resilience. While the debate continues as to what resilience is and what its constitutive elements are, what cannot be denied is that once a state is able to develop a special capacity to overcome innate challenges and make them part of its DNA and culture, its chances of all-round success and survival are much greater. This largely explains Singapore’s ability to immunise itself against various internal and external challenges, and to leverage on its various strengths, manage its weaknesses and come out stronger following adversity. Unlike many other newly independent states, Singapore’s approach to organising the state and its people included special efforts to ensure that national accommodation was achieved by leveraging its populace’s diversities and imbuing a sense of “oneness in many”. Through concerted efforts and socialisation, national resilience In Singapore is about developing an enduring capacity to cope with acute challenges and, more importantly, to recover, bounce back and emerge even stronger than before.1

What Is Resilience?

Even though the concept of resilience has been long associated with clinical science, its linkage with national security is relatively new, being a post-9/11 development.2 The rise in frequency and intensity of challenges, both natural and man-made, has compelled policymakers to think about how to prevent and preempt such disasters, and how best to protect societies and key infrastructures so that the state bounces back to its pre-crisis state quickly and resumes its functions in totality.3 The essence of resilience is to be prepared to respond to any threats that may eventuate. Resiliency is a multifaceted concept. It involves achieving a positive outcome in adversity, functioning effectively in adverse circumstances and recovering from a critical trauma.4 It is about distributing risk to avoid total paralysis if a disaster – say, a terrorist threat – succeeds. It is also about absorbing natural and unnatural disturbances while preserving the functions, structures and identity of the system.5 Additionally, it encompasses the notion that while it is imperative to prevent an attack from taking place, should an attack occur, it is equally vital that the government and people continue to function and bounce back.

While experts continue to debate the definition of resilience, more critical is the agreement that much needs to be done so that when a tragedy happens, there is no paralysis, only a sense of unity and more importantly a sense of purpose in regaining normalcy quickly. In short, resiliency is about developing a capacity and power to forestall disasters, be they natural or man-made.

Entrenching Resilience in the National Psyche

While Singapore is not the only heterogeneous state in the world, it is one with deep, acute and dangerous fault lines that, if not carefully managed, could easily destroy the nascent state, which has less than 50 years of national independence. On racial, religious, linguistic, cultural, economic and even historical grounds, the differences among Singaporeans cannot be sharper than they are.6 For many, Singapore will always remain an artificial construct as the pulls and pushes of differences and diversities have made the task of nation-building an onerous one.7 Not surprisingly, after more than 45 years of independent statehood, political leaders such as Lee Kuan Yew, Goh Chok Tong and Lee Hsien Loong continue to describe Singapore’s nation-building as a process that remains a “work-in-progress”. 8

Not only are racial and religious differences sharp, even more critical is Singapore’s limited geographical space with almost zero natural resources, and its location in a perpetual border pressure zone between Malaysia to the north and Indonesia to the south.9 Singapore is also highly dependent on the outside world for its basic resources, including water, not to mention the trading state’s investments and markets. With multiracialism, meritocracy and equal opportunity as the bedrock of societal management, Singapore stands out as a world-class successful “Chinese Island” in a “Malay Sea”, making geopolitics an extremely important determinant in national and international relations.

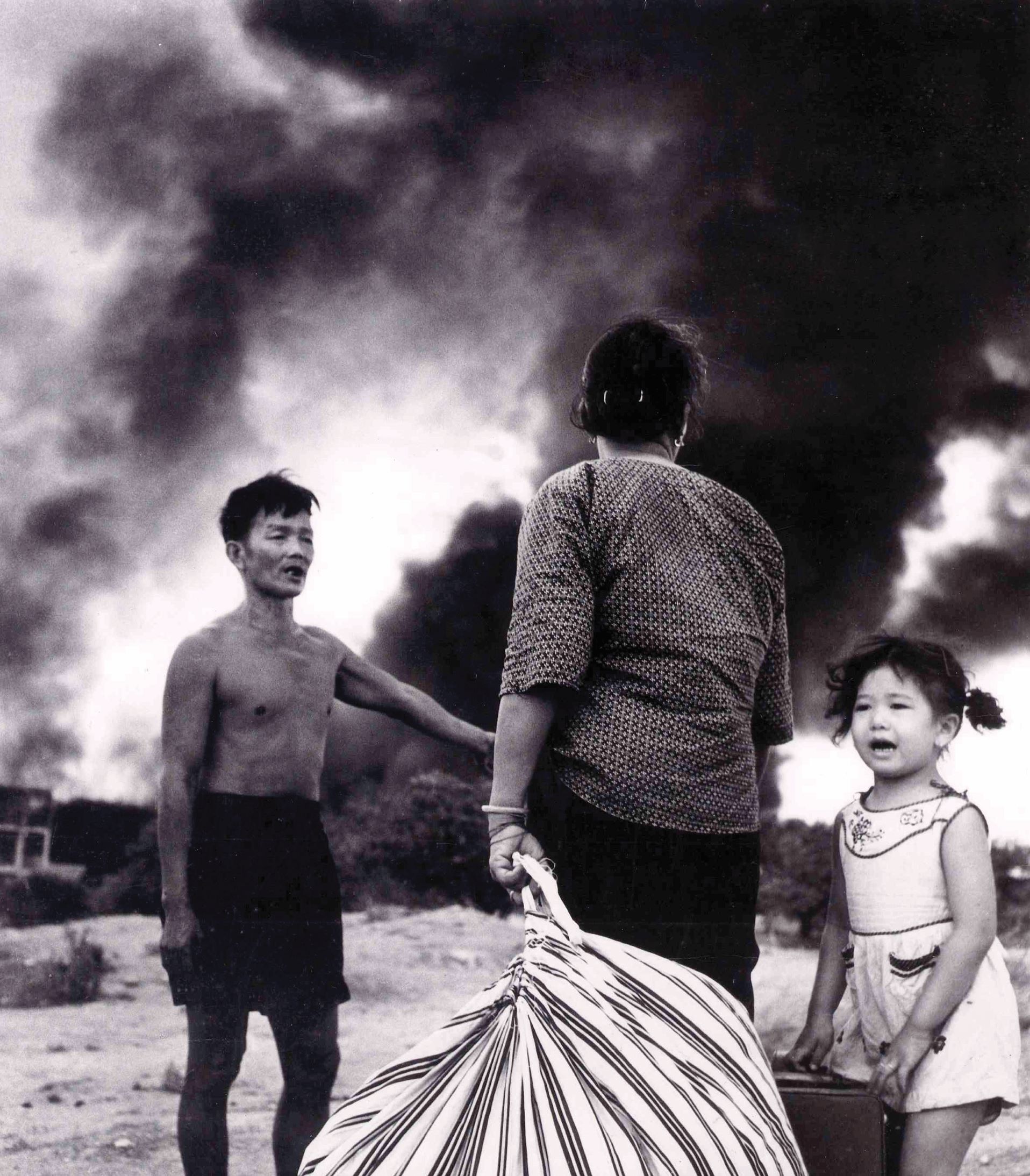

With multidimensional crises a perpetual feature that political leaders and people have had to face since World War II, peace and prosperity are not features that anyone in Singapore should take for granted. The difficult and dangerous past is a constant reminder that challenges, which can happen quickly and without warning, are looming just over the horizon. To survive, the political leadership and the people need to develop a special gene – defined today as national resilience – if Singapore is to not just continue to prosper, but to preserve its statehood.

Many multidimensional crises have shaped the psyche of Singapore’s leaders and its people: these include the brutal Japanese occupation, the racial riots of 1950, 1964 and 1969, Indonesia‘s Konfrontasi (Confrontation) against the Republic, and the threat of terrorism since the 9/11 attacks, among others.10 All these crises had serious implications for Singapore. However, the Republic’s leaders and its people responded with distinction, driven by the realisation that national societal resilience was critical if the Republic was to remain prosperous with its territorial integrity reaffirmed and safeguarded. National resilience is today regarded as an important national resource, the strengthening of which would greatly enhance the Republic’s security and place it in a strong position as far as international relations are concerned.

Mining Resilience for National Security

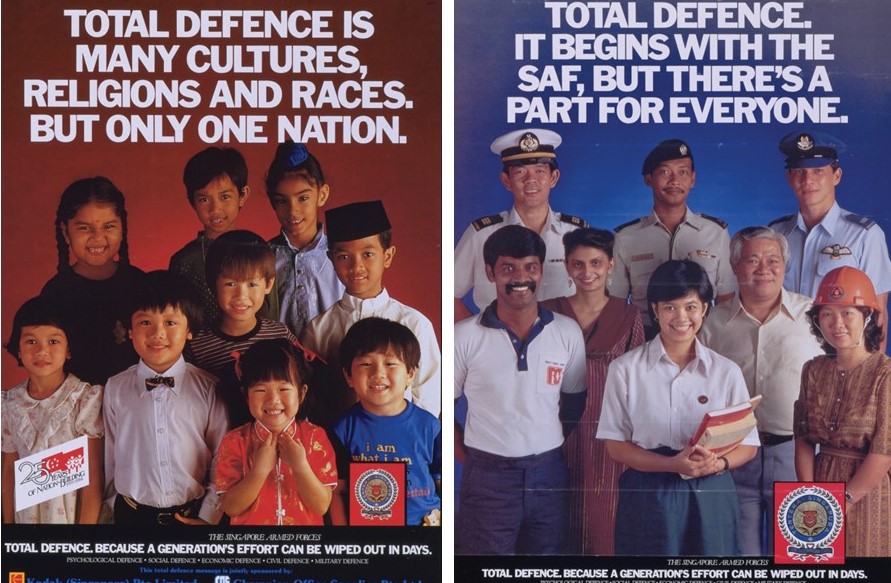

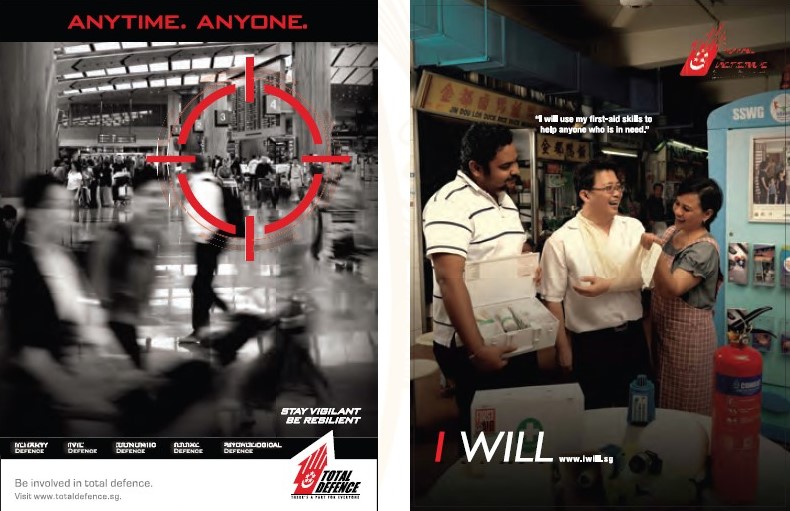

In response to various past challenges, the Singapore Ministry of Defence introduced the concept of Total Defence in 1984, which later permitted the concept of national resilience to be adopted as an important ingredient in enhancing national security. Learning from countries such as Switzerland, Sweden and Israel, there was a realisation that both traditional and nontraditional security threats could undermine the security of a state. In short, it was not sufficient to be militarily strong; the nation’s racial, religious and cultural cohesion as well as economic power were also invaluable security assets. In this regard, Total Defence encompasses Military, Civil, Economic, Social and Psychological Defence, representing the five critical sectors of any society.11 In some ways, these were both the hard and soft critical infrastructures of the Republic, and strengthening them required a whole-of-government and whole-of-society approach.

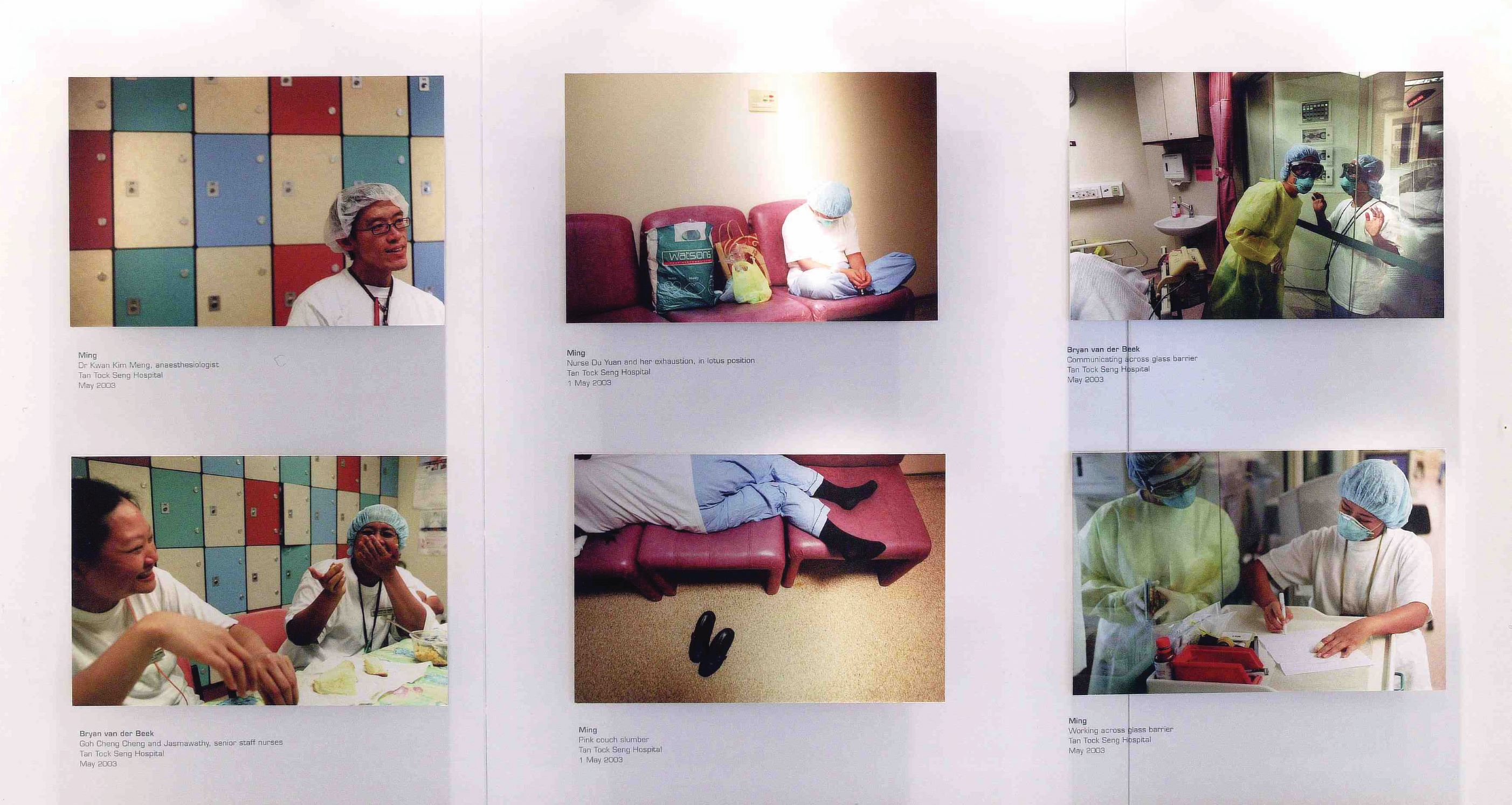

As resiliency has more to do with the traits, grit and determination of individuals and groups in a society, this easily dovetailed into the Psychological Defence component of Total Defence. However, following the Asian and Global Financial Crisis, the threat of terrorism, and SARS, resiliency was extended to other key elements of society, with a focus on social, psychological and economic resilience (as military and civil defence were considered already strongly embedded). Social, psychological and economic resilience were spotlighted, as these elements, if strong, permit a society to bounce back quickly after a crisis.12

As modern warfare, especially terrorism, is essentially psychological in nature, psychological resilience literally underpins national resilience. This necessitates that individuals take ownership of their lives while maintaining strong links with other members of society. In short, one must never give up. Admittedly, it is difficult to measure how psychologically resilient a society is. Nevertheless, referencing Japanese attitudes towards the recent earthquake, tsunami and nuclear disasters, one may gather that it involves individuals’ self-confidence and readiness to weather crises, a particular mental toughness as well as demonstrated social responsibility. On the broader societal level, this would involve mining a state’s social capital, sense of community spirit, volunteerism and sacrifice, as demonstrated by the workers at the Fukushima nuclear reactor, who continued working despite being exposed to radiation in order to secure northern Japan from radiation exposure.

Closely linked to psychological resilience, social resilience is growing in importance. This increasing emphasis is premised on the notion that for a state to overcome a crisis and bounce back from a tragedy, its people must remain united. For Singapore, being a multiethnic and multireligious society, this is all the more challenging in view of past experiences as well as the continued efforts to build inter-communal harmony and trust. Social resilience will be achieved as long as cohesion among the various racial and religious groups is maintained; this will ensure national resilience. In this regard, especially following the discovery of terrorist cells in the Republic in 2001, various efforts have been undertaken, including the launch of the Community Engagement Programme, Inter-racial and Religious Confidence Circles, and the Harmony Centre. There are also concerted efforts to engage the nation’s youths, those who did not experience the challenges of the 1950s and 1980s, mainly to inculcate sensitivities about each race so that this bonding of the nation begins bottom-up. Schools also celebrate Racial Harmony Day annually to imbue students with the value of racial and religious understanding and tolerance.13

Equally important, as Singapore is essentially a trading nation without any natural resources, is sustaining the economy, especially in a crisis. This is vital for its survival. Here, economic resilience becomes an important element of national resilience. Aside from the government, the role that the private sector and business community plays ensures that Singapore remains a resilient nation at all times. In this regard, Singapore’s economic well-being has been maintained by investing in various security-hardening measures as well as formulating policies that would ensure business continuities in times of crisis. A number of initiatives have been introduced, including the launch of a Safety and Security Watch Group, an Industry Safety and Watch Group, Corporate First Responder, Project Guardian and Business Continuity Management. The goal of these initiatives is to ensure that economically, the Republic would remain resilient even if there are natural or manmade disasters, which thus would keep the wheels of the national economy turning.

At the same time, through a whole-of-nation approach, education, mass media, housing policies and community leaders have been mobilised to function positively so that a “one heartbeat” culture can emerge. This is a very challenging endeavour mainly because of the immense diversity of the Republic, something further aggravated by the liberal migration policy that Singapore has adopted in the last decade and a half. Most importantly, schools have been mobilised to communicate national values that will help bond the nation, with National Education as the key pillar in this regard. Today, almost every aspect of the school curriculum is in one way or another linked to National Education, and the learning outcome of 10 years of basic education is an individual who is socialised and sensitised about the highly diverse peoples of Singapore and vulnerabilities that the state confronts. Thus begins the planting of the seeds of national resiliency for the long-term survival of Singapore.

National Resilience: Where Are We Today

As measuring national resiliency is almost impossible, this question is difficult to answer. The fact that the Republic has not witnessed any interracial or interreligious conflict since 1969 is one manifestation that not only is there a strong government with effective security policies in place, but society has become more tolerant and has developed an aversion to primordial conflict of this nature. In short, nation-building policies are on track and need to be maintained. However, with great efforts being expended on resilience-building, one might conclude that the sense of “oneness” has increased. This can be confirmed through various national surveys about feelings of nationalism, Singaporeans’ preparedness to tolerate, understand each other’s uniqueness, and coexist with one another. The public has also been supportive of national policies fostering close interracial and interreligious communication and dialogue. In short, the level of tolerance and understanding has increased markedly, especially in the public sphere, and this has a positive impact on national resilience. A sense of Singaporeanness is a powerful impetus for resiliency and one can say with confidence that Singapore is far more resilient today than it was in 1965.

At the same time, there has been an explicit sense of Singaporeanness emerging as evident from the public’s reaction to the government’s pro-migration policies. An unintended effect of the government’s liberal migration policies in the last decade and a half has been a rising consensus among Singaporeans that this poses a challenge to them in the long run, even though Singaporeans themselves are of migrant origin. This has had the effect of uniting Singaporeans in a common cause of opposing migrants, who are viewed as an all-round challenge, especially in the crowding of the public spaces in the already compact “little red dot”. The same negative reaction was also evident when sports personalities from abroad were imported to represent the Republic in international sporting events such as the Olympics and Commonwealth Games. Despite the victorious performances of these personalities (say, in table tennis), the euphoria of victory was missing as this was not viewed as “belonging to Singapore” and hence did not register as impactful on the Republic’s nationalism and patriotism. In short, the “Singaporean Us” has become more strongly manifested and probably embedded, as the “Immigrant Them” has come to be viewed as something that is not a natural part of being Singaporean, and hence rouses the feeling that these migrants do not belong here.

As the resiliency of a people is also about a sense of belonging, ironically, foreign migrants have helped Singaporeans to discover who they are and in the process cemented local nationalism.14 While the Chinese, Malay, Indian and Others (CMIO) boundaries are still relevant, these are also breaking down, especially in the public sphere, signalling the rising nationalism in the country.15 In some ways, the large numbers of migrants that have become part of Singapore’s recent demography have created “two Singapores”; the first Singapore is made up of the original inhabitants who closely identify with the national experiences, symbols and ethos of the Republic, and the second Singapore is made up of new migrants who are in Singapore primarily for economic motives and whose emotional bond is still with their mother country. While the bonding and resiliency among the “first Singaporeans” have been enhanced due to various socialisation policies and a fall-out from the government pro-migration policy, one can only wonder about the strength of the bond of the new migrants to the Republic, not to mention their ties with the original Singaporeans who have been signalling their unhappiness towards them. To that extent, while various government policies have cemented ties among Singaporeans and created a “single heartbeat”, at the same time, by importing more than a million foreigners into the city-state, at the macro level, the national glue has been somewhat diluted; in the process, national resilience has been weakened. One can only hope that this is a temporary phenomenon and a “one Singapore heartbeat” emerges sooner rather than later as a “two-speed” Singapore is counterproductive towards national resilience.

Regardless of the fallout from a liberal immigration policy and where foreign talent is vitally needed in the Republic, policies that would enhance and deepen national resilience need to be continuously nurtured. As a small, highly vulnerable territory devoid of natural resources, crises are likely to become part and parcel of Singapore’s existence. A special national gene and capacity would permit the Republic to weather these crises. In short, resilience would be required on almost a continual basis, and especially during crises. Therefore, it is largely irrelevant to inquire as to what stage of resilience the Republic is at today as much as it is vital to put in place the “hardware” and “software” that would permit Singapore to successfully confront any crisis that may come its way. This would also mean that if the Republic is to have any future at all, it will always require a leadership and a people that are resilient. Therein lays the key challenge as far as national resilience in Singapore is concerned, as any deficit and deficiency in this resource would sound the death knell for Singapore and its future.

Resiliency and Singapore’s Future

As Singapore matures as a nation and new challenges are identified, the concept of national resilience will become increasingly important in ensuing national security.16 While traditionally the government had assumed almost total responsibility for national security, with the launch of Total Defence and later a national-resilience approach, a whole-of-society pillar has been added to the whole-of-government strategy. While the government can undertake the “hardening” of critical infrastructures to ensure that key identifiable systems are protected from attacks, at the same time, by “hardening the populace” – the “soft anchor” of society, national resilience will be ensured. This will take a long time and every crisis successfully managed merely affirms the strengthening of national resilience as it signals that psychological, social and economic resilience has been tested and proves to be strong. The “we can do it” aspect will be strengthened, as will the “we shall overcome” spirit. Still, national resilience, like nation-building, will always be a work-in-progress. How the political elites galvanise the people will greatly impact the robustness of the society’s resilience. Since independence, Singapore’s national resilience has been strengthened and a sense of patriotism steadily imbued. The recognition that all are important stakeholders in this national enterprise merely confirms that national resilience is successful in making the state that much stronger. If successfully undertaken, it would also be a powerful deterrent to anyone who may want to harm the Republic as the people’s instincts to defend, self-sacrifice and recover from adversity will help to diffuse the threat of such attempts.

Associate Professor

Department of Political Science

National University of Singapore

REFERENCES

Anne Speckhard, “Civil Society’s Response to Mass Terrorism: Building Resilience” in Combating Terrorism – Military and Non Military Strategies,” in Combating Terrorism, ed. Rohan Gunaratna (Singapore: Eastern Universities Press, 2005), 113–23. (Call no. R 363.32 COM)

Bilveer Singh, Politics and Governance in Singapore: An Introduction (Singapore: McGraw-Hill Education (Asia), 2007). (Call no. RSING 320.95957 SIN)

Bilveer Singh, “A Small State’s Quest for Security: Operationalising Deterrence in Singapore’s Strategic Thinking,” in Imagining Singapore, 2nd ed., ed. Ban Kah Choon, Anne Pakir and Tong Chee Kiong (Singapore: Eastern Universities Press, 2004). (Call no. RSING 959.57 IMA)

Chan Heng Chee, Nation-Building in Southeast Asia: The Singapore Case (Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 1971). (Call no. RCLOS 320.95957 CHA)

Chan Heng Chee, Singapore: The Politics of Survival, 1965–1967 (Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1971). (From PublicationSG)

Chua Beng Huat, “Multiculturalism as Official Policy: A Critique of the Management of Difference in Singapore,” in Social Resilience in Singapore: Reflections from the London Bombings, ed. Norman Vasu (Singapore: Select Publishing, 2007), 51–80. (Call no. RSING 305.80095957 SOC)

Elgin Brunner and Jennifer Giroux, Examining Resilience: A Concept to Improve Societal Security and Technical Safety (Zurich: Crisis and Risk Network, Centre for Security Studies, 2009), 6—11.

Gary Hamel and Lisa Valikangas, “The Quest for Resilience”, Harvard Business Review, (September 2003): 52–63.

Gillian Koh, “Social Resilience and its Bases in Multicultural Singapore”, in Social Resilience in Singapore: Reflections from the London Bombings, ed. Norman Vasu (Singapore: Select Publishing, 2007), 27–50 (Call no. RSING 305.80095957 SOC)

Ingrid Schoon, Risk and Resilience: Adaptations in Changing Times (London, Cambridge University Press, 2006)

K.U. Menon, “National Resilience: From Bouncing Back to Prevention,” Ethos (January–March 2005): 14–17.

Michael Hill and Lian Kwen Fee, The Politics of Nation Building and Citizenship in Singapore. (London: Routledge, 1995). (Call no. RSING 306.095957 HIL)

Norman Vasu, ed., Social Resilience in Singapore: Reflections from the London Bombings (Singapore: Select Publishing, 2007), 51–67 (Call no. RSING 305.80095957 SOC)

Norman Vasu, “(En)countering Terrorism: Multiculturalism and Singapore,” Asian Ethnicity 9, no. 1 (2008): 17–32.

Speech by PM Lee Hsien Loong at the National CEDP Dialogue 2011, Singapore United, 19 March 2011.

Yolanda Chin and Norman Vasu, “Pledging Ourselves as One United People: A Study of Social Resilience in Singapore,” Centre of Excellence for National Security, S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, Nanyang Technological University, 8 February 2010.

Yolanda Chin, “Reviewing National Education: Can the Heart Be Taught Where the Home Is?” in Social Resilience in Singapore: Reflections from the London Bombings, ed. Norman Vasu (Singapore: Select Publishing, 2007). (Call no. RSING 305.80095957 SOC)

NOTES

-

Chan Heng Chee, Singapore: The Politics of Survival, 1965–1967 (Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1971). (From PublicationSG). Using “survival ideology” as the key approach to governance, values such as ruggedness, racial and religious tolerance, acceptance of change and sacrifice were imbued, signalling a “life and death” struggle, where doing the wrong things could prove terminal for the newly born state. ↩

-

Anne Speckhard, “Civil Society’s Response to Mass Terrorism: Building Resilience” in Combating Terrorism – Military and Non Military Strategies, in Rohan Gunaratna (ed.), Singapore: Eastern Universities Press, 2004. Notes on the History of Malayan Chinese New Literature, 1920–1942, ed. Kazuo Enoki. (Tokyo: Centre for East Asian Cultural Studies). (Call no. RSEA 895.1 FAN) ↩

-

Elgin Brunner and Jennifer Giroux, Examining Resilience: A Concept to Improve Societal Security and Technical Safety. Zurich: Crisis and Risk Network, Centre for Security Studies, 2009), 6–11. ↩

-

Ingrid Schoon, Risk and Resilience: Adaptations in Changing Times (London, Cambridge University Press, 2006), 7. ↩

-

Gary Hamel and Lisa Valikangas, “The Quest for Resilience”, Harvard Business Review, (September 2003): 62–75. ↩

-

Bilveer Singh, Politics and Governance in Singapore: An Introduction (Singapore: McGraw-Hill Education (Asia), 2007), 11–12. (Call no. RSING 320.95957 SIN) ↩

-

Michael Hill and Lian Kwen Fee, The Politics of Nation Building and Citizenship in Singapore. (London: Routledge, 1995). (Call no. RSING 306.095957 HIL) ↩

-

Hill and Lian, Politics of Nation Building and Citizenship, 104–05. ↩

-

See Bilveer Singh, “A Small State’s Quest for Security: Operationalising Deterrence in Singapore’s Strategic Thinking,” in Imagining Singapore, 2nd ed., ed. Ban Kah Choon, Anne Pakir and Tong Chee Kiong (Singapore: Eastern Universities Press, 2004), 114–5. (Call no. RSING 959.57 IMA) ↩

-

Chan Heng Chee, Nation-Building in Southeast Asia: The Singapore Case (Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 1971). (Call no. RCLOS 320.95957 CHA) ↩

-

Singh, “A Small State’s Quest for Security,” 128–29. ↩

-

K.U. Menon, “National Resilience: From Bouncing Back to Prevention,” Ethos (January–March 2005): 14–17. ↩

-

See Gillian Koh, “Social Resilience and Its Bases in Multicultural Singapore”, in Social Resilience in Singapore: Reflections from the London Bombings, ed. Norman Vasu (Singapore: Select Publishing, 2007), 27–50. (Call no. RSING 305.80095957 SOC); Chua Beng Huat, “Multiculturalism as Official Policy: A Critique of the Management of Difference in Singapore,” in Social Resilience in Singapore: Reflections from the London Bombings, ed. Norman Vasu (Singapore: Select Publishing, 2007), 51–67 (Call no. RSING 305.80095957 SOC); Yolanda Chin, “Reviewing National Education: Can the Heart be Taught Where the Home Is?” Social Resilience in Singapore: Reflections from the London Bombings, ed. Norman Vasu (Singapore: Select Publishing, 2007), 81–96. (Call no. RSING 305.80095957 SOC) ↩

-

See Norman Vasu, “(En)countering Terrorism: Multiculturalism and Singapore,” Asian Ethnicity 9, no. 1 (2008): 17–32. ↩

-

See Yolanda Chin and Norman Vasu, Pledging Ourselves as One United People: A Study of Social Resilience in Singapore, (Centre of Excellence for National Security, S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, Nanyang Technological University, 8 February 2010). ↩

-

For example, the speech by Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong at the National Community Engagement Programme Dialogue, 19 March 2011. ↩