Through His Eyes: Remembering Old Singapore Through the Poems of Edwin Thumboo

Singapore’s landscape is one that has undergone many changes through the ages. As we struggle to keep pace with change, development and modernity, we also race to document, remember and hold onto what Singapore was – and, by proxy, who we are.

Literature, like places, is also a recorder of history and a documentarian (however reliable) of passing time. As Mr S. Dhanabalan said, “[L]iterature is the keeper of a nation’s history for it deals with people’s lives, their small and big moments. It records their dreams, challenges, joy and pain through novels, plays and poems. Poets like Edwin Thumboo record for us permanently the people in our society and their history, their small everyday actions and the big life-changing moments, both public and personal.”1

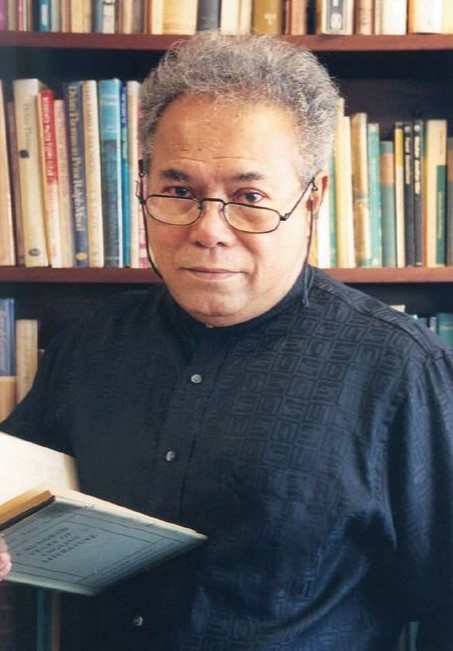

Remembering old Singapore and holding onto the spirit of old times are integral to Professor Edwin Thumboo’s poetry. One of Singapore’s most prominent poets, Thumboo’s works – in particular, his place poems – afford us glimpses into Singapore’s history. Having lived through Singapore’s pre- and post-independence days, Thumboo’s poetry brings to life our nation’s past and struggles, the atmosphere of days gone by and showcases its progress and changing physical landscape.

Even for a nation as young as Singapore, enough time has passed that attachment to particular places are formed. Places and spaces are important markers for a people: places provide a common ground within which a community interacts and shapes its identity, and are “closely intertwined with individual and collective biographies”.2 In other words, we imbue the spaces we inhabit with meaning and memories, thus building invisible landscapes upon physical ones. As Brenda S.A. Yeoh and Lily Kong wrote: “[P]laces thus have a ‘depth’ which goes beyond the invisible landscape: they contain layers of meaning derived from different biographies and histories. Place meanings are further strengthened when levels of personal biography and collective history are compounded.”3

The passage of time is marked by our changing city. Singapore’s journey from kampongs to multistorey public housing, from old “mama” shops to massive shopping malls, showcases our past, present and hopes for the future. Most Singaporeans have seen these changes happen throughout their lifetime. Ironically, this rapid change has given rise to a groundswell of nostalgia in all sorts of ways – many shops, homes, cafes and hotel spaces now boast retro interior design (a choice vintage sofa here, an old-fashioned typewriter there); fashion is part of this rising trend (as seen in how the 1960s style made a comeback in renewed forms). “Nostalgia is likely when social change is rapid enough to be detectable in one lifetime at the same time, there must be available evidences of the past… to remind one of how things used to be.”4 Places and buildings are among the most visible evidence and links to the past – and they help anchor our memories and identities.

Places as Anchors

In an interview with iremembersg (the blog of the Singapore Memory Project), Jaime Koh of The History Workroom said, “[T]he growing sense of nostalgia is a result of the too-rapid changes in modern societies. Things change so fast that there is hardly any time to cultivate any sort of bonds or sentiments. The past, then, becomes an anchor that provides some sort of stability in the rapidly changing society.”5 The past – and places – act as a focal point for the community and is a way in which Singaporeans can bond and strengthen unity. These old places are, literally, common ground.

Old places make an otherwise invisible history visible – not only in terms of the political and social history of a place, but in terms of a community’s shared and personal histories. The places that we give meaning to are not necessarily gazetted buildings or monuments; they are homes, playgrounds, streets, even foodstalls, places that are ordinary.

Former Senior Minister S. Rajaratnam once said, “A nation must have memory to give it a sense of cohesion, continuity and identity. The longer the past, the greater the awareness of a nation’s identity… A sense of common history is what provides the links to hold together a people who came from the four corners of the earth.”6 Places are visual markers of our common history, our shared identities, and when places like these are filled with meaning and memories, they give our culture a new dimension: they give it soul. These shared experiences transcend things such as race or religion that threaten to divide; they remind us of the ties that bind.

Places and Identity

Perhaps, then, this seemingly rising obsession with all things old in Singapore is symptomatic of a people who are still trying to make sense of their own identities – as individuals and as a country. As familiar buildings disappear and new ones replace them, we experience a sense of loss – a loss of identity that “is attached to places that evoke shared memories… identity [that is] derived from places that are important to everyday living”.7

The rise of nostalgia in Singapore, especially among its younger generations, can be construed as part fad, but also part search for the Singaporean identity. Thumboo’s works offer the younger generations an interesting glimpse into the past and how things used to be – the past is given shape and form, but the reader is allowed to explore and develop his or her own conclusions and interpretations. Physical spaces that have history and meaning ascribed to them are limited in the narratives they showcase.

Threatened with a sense of rootlessness, searching for a personal, cultural and national identity and assailed by the media and all the choice offerings of globalisation, it is no wonder that the younger generations are looking back. This perceived identity crisis of younger Singaporeans is nothing new: a 1999 survey found that an alarmingly high proportion of Singaporean students preferred to be Caucasian or Japanese.8

The subject of national identity is one that is close to Thumboo’s heart – having lived through Singapore’s pre- and post-independence days, he understands what it took for the country to make it from third world to first. He acknowledges that while every Singaporean’s ethnic background is different, it is the common experiences we share despite our racial or religious differences that will make us truly Singaporean: “While we document and enliven our heritage as Chinese, Malays, Indians and Eurasians, we concurrently search for their crosscultural contact, content and context that have marked, and continue to mark our rising into a nation. We have moved, and continue to move. Increasingly, the label, Malay, Chinese, Indian and Eurasian Singaporean, reverses its term putting Singaporean first. This reconfiguration is a source of essential strength, much needed in an age of rampant globalisation, which tends to reduce national identity as a concept, and reality plays a crucial role in establishing and consolidating our sense of self and of nation.”9 A substantial part of our national identity is gleaned from our shared history, and not remembering where we came from will have repercussions on our common identity.

Edwin Thumboo’s Poetry as Documentation

Think of old spaces as time machines – visiting, seeing, being in them teleports us back to the past and we are reminded of what things used to be like; they are visual markers of where we came from. They are “prodigious (but not unproblematic) recorders of the passage of history. Not only do social and cultural changes necessarily occur in places, they are often inscribed and transmitted in places”.10 But the history ascribed to a place, especially personal histories, is fluid – what is remembered, what is passed down to future generations is dependent on what “particular historical ‘truths’” are important and emphasised. This means that the history and meaning of a place is wont to change. Radical change, such as demolition of places (Hock Lam Street and the National Library at Stamford Road) may “obscure or obliterate” place histories. It might be difficult to decipher the truth in physical spaces, but in contrast to this notion, Thumboo says that “we should put the truth of experience into language.”10 But the history ascribed to a place, especially personal histories, is fluid: what is remembered, what is passed down to future generations is dependent on what “particular historical ‘truths’” are important and emphasised. This means that the history and meaning of a place are wont to change. Radical change, such as demolition of places like Hock Lam Street and the National Library on Stamford Road may “obscure or obliterate” place histories. It might be difficult to decipher the truth in physical spaces, but in contrast to this notion, Thumboo says that “we should put the truth of experience into language”.11

People attribute different memories and meanings to the same spaces. The National Library Building on Victoria Street, for instance, might represent days spent with friends, studying for exams, first loves and so on. However, this same space that is known for “browsing, research and perhaps, as a venue for casual meet-ups, it is for Thumboo and his contemporaries a hard-won fruit of their generation’s labour for independence in more hostile climes. The National Library, as a landmark, is a triumphant testimony to the virtues of life-long learning for his generation and it provides an intellectual armour against a past weakened by the shackles of a none-too-distant colonial administration”.12

Thumboo’s poem, “The Sneeze”, was written about hawkers along Hock Lam Street, where Funan DigitaLife Mall now stands. His playful poem brings to life the hustle and bustle (and suspicious hygiene) of Hock Lam Street. Younger generations may not know Hock Lam Street, but through Thumboo’s poem, we are able to peer through the veil of time and experience Hock Lam Street for ourselves:

Selling mee and kway-teow

Is prosperous, round

Quick moving

With practised grace

He blows his nose,

Tweeks it dexterously, secures complete evacuation

Then proceeds to comply with the slogans,

The injunctions on the need to

Keep Singapore clean—

Keep Singapore germ-free

Keep Singapore…

Besides the sample of old Singapore life, Thumboo succinctly highlights a slice of nation-building – where Singapore was striving for better health standards, and campaigns to educate the public were everywhere. In the poem, the hawker, too, interprets and acts on these public campaign in his own charming way: “By wiping his fingers thoroughly on his apron./He is not going to dirty the drains,/Clutter the spittoons./he obeys the law,/Deals with his cold seriously.” In the name of progress, it might not have been possible to preserve or save Hock Lam Street, but Thumboo’s poem has immortalised the street, and penned it for posterity.

“[Thumboo’s] place poems are rich emblems of public memory and private reminiscences, they are also relics of Singapore’s colonial heritage and timeless reminders of the struggles as well as successes our Republic has witnessed in the pre- and post-independence years.”13

In writing about these places from his personal memory, places that have been lost, Professor Thumboo has provided a focal point for these places – and all the memories associated with them – to flourish. His poems act as time capsules, or even a time-travel machine, bringing the reader from past to present. He transports readers back to a time that they both might remember:

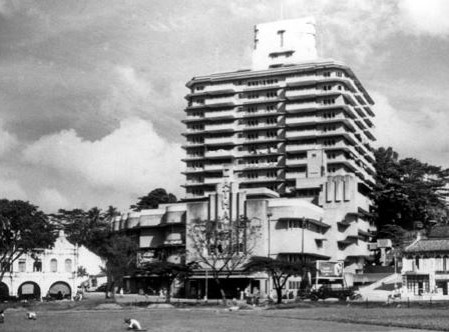

Where the first Rendezvous brooded

By a row of old shophouses, since sadly slain,

A special road began. A point of colonial

Confluence: Dhoby Ghaut, the YMCA with

Manicured tennis lawns for Memsahibs who

Then took tea and scones. Across a Shell kiosk

Where Papa parked his Austin Seven, then off

To Hock Hoe’s for piston rods and Radex.

The three Cathays, a name the Lokes made

Famous: resplendent building, our tallest then;

Fantastic camera shop; and that popular Store

Where Rudy’s wife, petite, temporarily demure,

Quietly assessed her customers as she held her

Intelligence above show-cases. Two doors away,

Heng, increasingly called Mr, sold German cameras

To Japanese sailors, was en route to a partnership...

Central to his writing are all the emotional ties and sense of belonging that come with a place. In “Bras Basah” he continues to set the scene of the area with nuances and insights: “And the bookshops full of stuff ”, “And the Rendezvous after school; affordable/The man with the mole, ladle in hand…”, “Simon Ong’s Family shop of fishing tackle…” and “a Woodsville tram,/Full of St Andrew boys, swings around the corner,/Tires squealing”. In this sense, his works do what the preservation of physical buildings cannot: in essence, he recreates the Bras Basah of his memories, replete with the sights, the sounds, the sense of place that is Bras Basah.

His poems give voice to the nostalgic-laden, time-worn, reader. “A sense of place with all its multifarious meanings, is thus an integral element in the conceptions of history, nostalgia and heritage. As a concrete localised setting, place provides the receptacle for the outworkings of history… [it is also] intimately drawn into individual interpretations [and] social constructions.”14 Thus, in place of an actual location, Thumboo’s poetry provides readers with a means through which to work out their own understanding of place, it gives readers a space – within themselves – to work out their own identity and history.

Nostalgia tends to sweep undesirable memories under the carpet, presenting a rose-tinted or sugarcoated version of history. Thumboo’s works remove the veil of nostalgia, the rose-stained glasses of sentiment and remember the days past with clarity, in all its dust and pain, which are seen through his poems like “Government Quarters Monk’s Hill Terrace, Newton, Singapore”, wherein he acknowledges the hardships and harsh realities of World War II.

In this poem, he explores life under the Japanese occupation, life under “The Japanese sun floated free, confidently/Ruling Syonan skies from that high perch”, where he experiences a loss of innocence, and a sense of longing and yearning for time past, where “At day’s end, a boy again; too shut down/To wish, to dream. But when I did, mostly/Pre-war life, in Mandai, my sloping Eden”. While his childhood home at No. 42 Monk’s Hill Terrace has since been demolished, what remains through his poetry is not only the life he once led, not just his memories and feelings of the place, but the sentiment of mourning and loss coupled with the beginnings of nationalist sentiment (“From that veranda that releasing September, that/Union Jack again. From the papers, British power/Restored. From the radio, patriotic songs recalling/Pomp and power, the Land of Hope and Glory,/Mother of the Free; not yours, not mine, not ours.”).

Thumboo not only charts the changing icons of Singapore’s cityscape (“The National Library, nr. Dhoby Ghaut, Singapore”; “The National Library, Bugis” and “Double Helix, Promenade”), he also turns his literary eye upon everyday housing estates, documenting and capturing snapshots or slices of Singapore life in “Evening by Batok Town”: “Vigilant Bukit Batok topped by radar;/MRT accompanying Avenue 5;/Four-point blocks, JC, food-centre;/A young couple held by privacy/Amidst strolling families”. But he juxtaposes the familiar with memories of what Bukit Batok used to be like, also an indication of the speed of change in Singapore and, sadly, our inclination to forget:

When little Guilin had no pools.

Before that the green slope of hills

Descended into plain and swamp.

Before that an old geology. Squatters

Cleared land, directed streams, built

Ponds, a temple to guardian deities; then

The quarry-road the Indians made, re-named

Perang to meet the lurking yellow peril.

Out of such energies, such history, a town.

The new breed in search of

Gleaming jobs, the computer-mind,

Turn memory shorter than the land’s.

Thumboo’s poem, “Bukit Panjang, Hill, Village, Town” (and also one of his longest in recent years), succinctly surmises the evolution of Bukit Panjang from when it “Culled our season years before we/ Glimpsed your contours. You/ Rolled south to be the tip of Mother Asia,/ Picking up names like Bukit Batok. You/ Finally stopped for tectonic breath, at Mt/ Sophia” to when it had “Small clusters of rubber, durian, Mango,/ Tembusu, pulasan, mangosteen”. But more than just its physical evolution, Thumboo infuses his poem with history, making references to Bukit Batok during key points in Singapore’s history, mirroring the growth of Bukit Batok with that of Singapore’s: “your last spur is Fort Canning./ Still steady stately un-stressed, you/ Our vigilant secret dragon saw your further / Than Brit radars” and “Trying to spot Konfrontasi: a word, a fear,/ A rant” Thumboo’s poetry is more than a recounting of the shifting cityscape of Singapore: it is a recounting of the country’s story. This is particularly pertinent in “Bukit Panjang, Hill, Village, Town”:

Thumboo’s poetry functions in the same vein as old places – he uses text to recreate or even preserve physical spaces familiar to us, and infuses them with emotion, history and meaning, filling it with significance. His poetry documents our progress as a nation through the changes in its landscape, marking out particular moments through his personal memories and experiences, his own thoughts and ruminations, and then leaves us to our own reflections and conclusions. Both physical spaces as well as literary ones work in tandem to help to “preserve the past, [and] ensure the future”.

REFERENCES

Gwee, L.S., & Heng, M. (Eds.). (2012). Edwin Thumboo: Time-travelling: A selected annotated bibliography. Singapore: National Library Board. (Call no.: RSING S821 EDW)

Heng, M. (2012). Introduction. In E. Thumboo, Singapore word maps: A chapbook of Edwin Thumboo’s new and selected place poems. Singapore: National Library Board. (Call no.: RSING S821 THU)

Pee, S. (2012, September 19). Interview with the History Workroom. Retrieved from iremembersg.

Richardson, M. (1999, December 20). Singapore identity crisis? Youths would rather be white or Japanese. International Herald Tribune. Retrieved from Factiva via NLB’s eResources website.

Speech by Mr S. Dhanabalan at the launch of “Edwin Thumboo, Time Travelling, A Poetry Exhibition”, 29 September 2012.

Speech by Professor Edwin Thumboo at the launch of “Edwin Thumboo, Time Travelling, A Poetry Exhibition”, 29 September 2012.

Tan, Y.L. (2001, May 2). Don’t demolish identity markers. The Straits Times. Retrieved from Factiva via NLB’s eResources website.

Yeoh, B., & Kong, L. (1996). The notion of place in the construction in history, nostalgia and heritage in Singapore. Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography, 17(1), 52–65.

NOTES

-

Speech by Mr S. Dhanabalan at the launch of “Edwin Thumboo, Time Travelling, A Poetry Exhibition”, 29 September 2012. ↩

-

Yeoh, B., & Kong, L. (1996). The notion of place in the construction in history, nostalgia and heritage in Singapore. Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography, 17 (1), 52–65. ↩

-

Yeoh & Kong, 1996, pp. 52–65. ↩

-

Yeoh & Kong, 1996, p. 57. ↩

-

Pee, S. (2012, September 19). Interview with The History Workroom. Retrieved from iremembersg. ↩

-

Yeoh & Kong, 1996, p. 58. ↩

-

Tan, Y.L. (2001, May 2). Don’t demolish identity markers. The Straits Times. Retrieved from Factiva via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

Richardson, M. (1999, December 20). Singapore identity crisis? Youths would rather be white or Japanese. International Herald Tribune. Retrieved from Factiva via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

Speech by Professor Edwin Thumboo at the launch of “Edwin Thumboo, Time Travelling, A Poetry Exhibition”, 29 September 2012. ↩

-

Speech by Professor Edwin Thumboo, 29 Sep 2012. ↩

-

Heng, M. (2012). Introduction. In E. Thumboo, Singapore word maps: A chapbook of Edwin Thumboo’s new and selected place poems (p. 8). Singapore: National Library. (Call no.: RSING S821 THU) ↩

-

Yeoh & Kong, 1996, p. 61. ↩