Chinese Rice Commerce and the Transformation of Sai Gon–Cho Lon in Colonial Vietnam

In the mid-19th century, as the French empire began to consolidate its foothold in Southeast Asia, the Chinese rice trade became the cornerstone of the colonial economy. On the back of this trade, the port city of Sài Gòn– Chợ Lớn grew to become a major urban centre and international entrepot, and by the late 19th century, Indochina was the third-largest global rice exporter after British Burma and Siam.1 At the heart of this trade were Chinese migrants, whose transnational mercantile networks provided the financial scaffolding for French colonial capitalism. Christopher Goscha characterises this thriving trade as a striking manifestation of “East Asian modernity at work”, and asserts that along with alcohol monopoly and the development of the colonial plantation system, “the rice trade constitutes one of the most important components of the Vietnamese economy to this day”.2

Through the lens of the rice trade, this paper examines the confluence of Chinese migration and diasporic capitalism in transforming Sài Gòn–Chợ Lớn in the 1870s into a central trade emporium and prominent colonial port city crucial to the development of French governance in Vietnam and Southeast Asia at large. My research relies on both primary and secondary materials in the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library at the National Library of Singapore, especially the under-explored Singapore historical newspapers in the NewspaperSG archive, which offers invaluable insights into southern Vietnam and its Chinese communities. Eclectic information on the rice trade and Chinese roles in it extracted from colonial Singapore–era newspapers sheds new light on our understanding of the scope of this trade’s influence and the close interactions between Franco-British imperial powers and Chinese communities in the Nanyang diasporic network. Although the relevant materials and accounts are relatively fragmented, they show the presence of Chinese commercial activities and the urbanisation of southern Vietnam at the height of European colonisation in the region, a testament to the spread of the Chinese population and their importance as politicoeconomic contributors across Southeast Asian port cities. Hence, these sources are more than mere supplements to archival sources in Vietnamese and French.

A Sketch of Sài Gòn–Chợ Lớn’s Chinese Migration and Its Communities

Chinese migration to Vietnam and participation in its economy are part of a larger history of Sino-Vietnamese interaction, conflict and state-building spanning centuries. In southern Vietnam, the first massive wave of Chinese migrants came at the fall of the Ming dynasty in 1644. Groups of Ming loyalists escaping persecution by the Manchu-ruled Qing dynasty settled down in coastal areas of modern-day Vietnam, including Hội An, Qui Nhơn, Sài Gòn and Hà Tiên. Under the Nguyễn lords’ open attitude towards the refugees’ integration and their involvement in commercial trade, the Chinese population in the south grew quickly, with a rough estimate of 30,000–40,000 people in total in southern Vietnam towards the end of the 18th century.3 These Chinese and their descendants were collectively referred to by the Sino-Vietnamese term, Minh Hương (明香; ming xiang in Chinese, or literally “Ming incense”, in reference to their ancestry as Ming refugees).4

The fall of the Ming also saw the Chinese become increasingly intertwined with imperial politics in southern Vietnam. In 1679, 3,000 Chinese troops, led by two anti-Qing military generals, Trần Thượng Xuyên and Dương Ngạn Địch, arrived at the central Vietnamese port of Tourane. This coincided with Nguyễn Hoàng’s near-complete acquisition of the southeastern and western Transbassac.5 When the two generals pledged loyalty to the Nguyễn lord and asked for permission to take refuge in southern Vietnam, they were welcomed with open arms, given the strategic position of Cochinchina as a key commercial centre in a flourishing maritime trade network and the Sino-Japanese-Vietnamese alliances from which the Nguyễn clan drew its power.

In the early 18th century, a Chinese general-in-exile named Mạc Cửu furthered Nguyễn Hoàng’s imperial ambitions through the conquest of Hà Tiên, a key southernmost coastal town, at the expense of Cambodia, turning it into a prosperous and profitable Chinese “colony”.6 Thus, well before the Tây Sơn Uprising in 1771, Ming-loyalist Chinese had established themselves in Cochinchina as powerful merchants, mariners, court officials and military leaders who were accorded with political and economic privileges that outpaced their Vietnamese counterparts. The fact that both sides of the Tây Sơn rivalries (1771–1802) – Nguyễn Huệ’s forces and the Nguyễn lord’s armies – relied heavily on Minh Hương attests to their critical role in Southern imperial politics.7 The Minh Hương provided critical resources and support to recruit soldiers and finance military operations.

While their identities became diluted towards the end of this conflict, their status and influence as an institutionalised “bureaucratic-mercantile ‘minority elite’” did not cease with the new Nguyễn dynasty at the turn of the 19th century.8 Emperor Gia Long (Nguyễn Ánh) allowed Minh Hương to be registered as permanent settlers as opposed to itinerant merchants or sojourners and continued to recognise them as an official minority within the state. This enabled them to form distinct communities residing in separate administrative units called Minh Hương Xã or Minh Hương villages. Members of Minh Hương Xã, classed as ethnic Chinese, enjoyed reduced taxes and access to official court positions, while being exempted from mandatory military conscription and forced labour.9

This situation shifted drastically when Gia Long’s son, Emperor Minh Mạng (r. 1820–41), pursued aggressive policies to assimilate the Chinese into mainstream Vietnamese society. In 1829, Chinese migrants were banned from going back to China, and in 1842, they were accorded a different immigration status from those arriving later – now designated as the immigrant Chinese (immigrants chinois).10

Minh Hương as a category thus began to develop new legal connotations. Those identified by the imperial court as members of this group now included anyone of ethnic Chinese descent, including the offspring of Chinese and Vietnamese intermarriages, i.e. métisses or mixed race, often referred to as Sino-Vietnamese. By joining a Nguyễn-legislated association of Minh Hương villages, Chinese settlers were encouraged to interact with local villagers and adopt Vietnamese cultural practices. For example, Minh Hương children were prohibited from “shaving their heads and wearing pigtails… and must be registered as a member of the Minh Hương congregation when they reached eighteen and abandon their parents’ nationalities”.11

As the Nguyễn polity expanded its territories southward, ongoing settlements and economic potential in the Mekong Delta presented numerous opportunities for further Chinese migration. Between 1829 and 1830, just over 1,100 Chinese arrived at the district of Gia Định. From the last

two months of 1830 to the first four months of 1831, about 1,640 more settled in the area.12

Under the Nguyễn dynasty, Chinese migration and settlement were regulated by a system called bang, in which the migrants were categorised into dialect-based communities. Each bang nominated its own head officers to communicate with the Nguyễn court on political and economic issues. This system of control was perfected under the French when they nominally ruled over the southern colony of Cochinchina. The French system, called congrégation, required all Chinese to be registered and taxed based on their place of origin. By 1871, seven native-place associations were recognised by colonial law: Canton, Fujian, Hakka, Hainan, Chaozhou (Teochew), Fuzhou and Quanzhou.13

The French sought to benefit from the pre-existing Chinese economic networks, including their diasporic trade routes and their competitive advantage over indigenous populations in “rice production, fisheries, and other staple industries”.14The Chinese were also valuable intermediaries who filled the French coloniser’s manpower needs and provided key sources of income to thicken the colonial budget. For example, the Chineseoperated opium revenue farms were the financial mainstay of the colonial bureaucracy.15 But, as Li Tana remarks, “at the heart of Chinese commerce in Vietnam, the rice trade was the main index of Chinese prosperity”.16Indeed, with the emergence of Sài Gòn as a cosmopolitan coastal city and Chợ Lớn as its adjacent Chinatown, the Chinese came to dominate this prized segment within the colonial economy of Cochinchina.

Chinese Rice Commerce, Colonial Port City, and the Making of a Trans-regional Trade

Thomas Engelbert aptly describes the city of Chợ Lớn as the rice capital of colonial Cochinchina; the existing Chinese social and commercial structures conducive to efficient business-making, and the rapid urbanisation of Sài Gòn made Chợ Lớn an important centre of commerce in the Mekong Delta trading emporium.17 Two intertwined dimensions account for the rise of Sài Gòn–Chợ Lớn: French colonialism and Chinese economic networks.

French colonialism changed the face of both the formerly waterlogged city of Sài Gòn and the little town of Chợ Lớn 6 km away. Before the French conquest in 1859, Sài Gòn was generally described by local imperial officials as naturally well endowed, having benefited from the rich resources of the Mekong Delta and its water-based navigational systems. European visitors, however, viewed it with much doubt and contempt, seeing it as a swampy area with sporadic commercial exchanges and a bleak future for infrastructural development.18 Decades after French efforts to transform the region through economic modernisation programmes and public work projects, however, British observers presented a different opinion, calling Sài Gòn “the Paris of the East” and “the Pearl of the Orient” as they waxed lyrical about its exuberant modernity:

The streets become wider, the houses and shops more

resplendent,

and further on, as we approach the beautiful cathedral, we come

across wide boulevards, and pass beautiful residences of the

French inhabitants and fine government buildings… The cost of

living in Sài Gòn must be extremely high.19

The city’s bustling commerce was also noted. 20 Some visitors could not help but compare it to Singapore – then Sài Gòn’s most important trading partner but also occasional competitor – and admiringly proclaimed it “a progressive city” and “the future queen of the East”.21 Reporting on the state of commerce in Sài Gòn–Chợ Lớn with vested interest and wariness, the Straits Times scrupulously cited statistics from its correspondents: “the tonnage frequenting the port rose from 834,430 tons in 1902 to 1,695,515 tons in 1907”, and “the volume of trade in imports and exports together shot up from a value of over 259 million francs in 1902 to nearly 892 million in 1907”.22

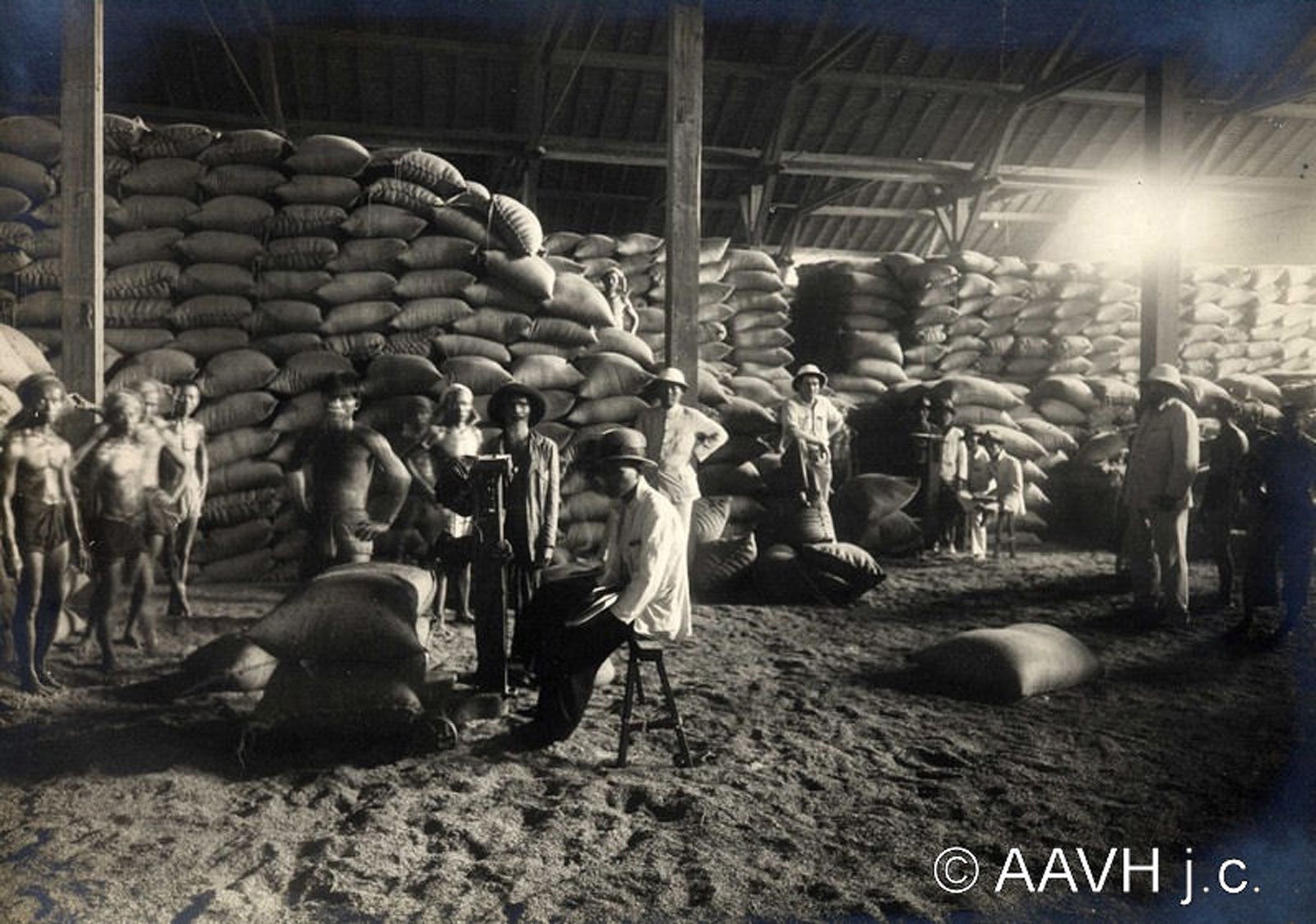

Over in Chợ Lớn, the robust Chinese presence and vibrant trading scene captivated foreign investors. One called it a “veritable Chinese town” in a city of abundance, where a large number of British traders came in the spring and winter months to search for rice cargoes, and where “all the large rice mills – the largest to the east of Singapore” were to be found.23

The so-called modern development of Sài Gòn as a port city began with intensive hydraulic projects in the 1860s to facilitate colonial control and access to the more remote parts of the south. A new colonial administration was put in place to supervise the construction of complex canal networks connecting the coastal cities to the hinterlands and the waterways of the Mekong Delta.

According to the Director of the Interior, Paulin Vial, who monitored this early phase of public works already underway two years prior to the conquest of Sài Gòn, these projects reshaped the urban geography of the city and the topography of Cochinchina at large. “Two thousands of workers were employed from all parts of Cochinchina,” he wrote, “to pull the entire city out of its muddy state and, most importantly, to stimulate its function as a port authority with well-operated wharves and smooth-sailing traffic”.24

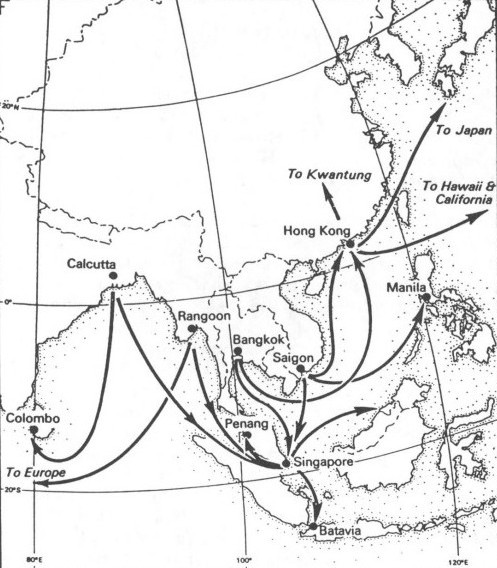

Specifically for the Cochinchinese rice trade, this period of feverish construction improved existing waterways, initiated new agricultural zones, and therefore accommodated rice cultivation by Vietnamese settlers along these routes. A new canal, Arroyo Chinois (Kênh Tàu Hũ), greatly improved access to the more distant Transbassac areas. This effectively linked the rural rice economy of Miền Tây to the rice mills in Chợ Lớn and, via the port of Sài Gòn, to global rice-export powerhouses such as Hong Kong, Canton, Singapore, Manila, Bangkok and the Netherlands East Indies.25

This increasing interconnectedness of the international rice markets led to an exponential growth in exports in Sài Gòn from 1860 to 1919.26 Rice, alongside pepper, became one of the two major export commodities for the colonial economy. According to the Sài Gòn Chamber of Commerce, approximately 58,000 tons of rice were exported to Europe and other global markets from Sài Gòn in 1860, and from 1865 to 1869, rice prices in Cochinchina achieved the highest index for export.27 Only seven years later, this number increased more than threefold to about 193,000 tons. From the 1880s onwards, Cochinchina exported half a million tons annually, accounting for 80 percent of the total value of southern Vietnam’s exports.28

The unprecedented boom in commercial rice export was supported by the activities of various Chinese communities in southern Vietnam around this time – predominantly traders, rice millers and go-between workers of all kinds, but also financiers and creditors.29 Chinese rice commerce was organised through an elaborate network of what anthropologist Clifton Barton characterises as an urban-rural dynamic. It involved the co-participation of urban rice merchant syndicates (centred on Chợ Lớn) and village-based Chinese traders, who together forged a link between Vietnamese rural society and the colonial commercial economy.30 In addition to their significant contribution to the French colonisation of the Mekong Delta and its agricultural revolution, Chinese merchants were, in Barton’s words, “the channel through which much of the credit that financed these development efforts flowed and the source of the merchandise that provided the incentives for Vietnamese peasants to produce for the market economy”.31

The Chinese pioneered rice-grinding technologies that gave their mills an edge in efficiency. In 1876, the first steam-powered mill in Chợ Lớn was assembled and popularised by a Chinese merchant there.32 In 1906 and 1907, two large rice mills in Chợ Lớn – Ban Tek Guan and Ban Hong Guan – struck a deal with the engineering firm Messrs. Riley, Hargreaves and Co. to provide extensive electrical installation for their mills, and to supply “the dynamo as well as the other gear”.33 The Singapore-based British firm

claimed that their electrical engines would be “more than sufficient to run over 600 lamps of 16 candle power in addition to several arc lamps”.34

By the late 19th century, the Chinese owned the majority of Cochin-chinese mills. Of the eight rice mills in Sài Gòn–Chợ Lớn, it was believed that five belonged to Chinese proprietors.35 Nationally, until 1911, Vietnam had a total of 30 rice mills (23 in Sài Gòn and the six southern provinces, 6 in Tonkin, and 1 in Tourane); of these, 24 (accounting for 80 percent) were Chinese-owned. In terms of productivity, owing to technological innovations and sheer numerical advantage over the French, Chinese mills reached an efficiency level of 500–1,200 tons per day.36

The Chinese compradors in Chợ Lớn also monopolised access to the coveted young rice grains (lúa non) from Vietnamese farmers. Around December each year, Chợ Lớn’s mills sent out armies of agents to scout the interior of Cochin-china for junks managed by Chinese overseers to procure paddies. These agents, or “bosses”, served as the most proactive and persuasive middlemen. Accompanied by local partners, they cultivated congenial relationships with Vietnamese farmers to buy their crops in the best condition.

In this way, the Chinese rice merchants of Chợ Lớn built up close connections with the local farming populations and landlords (điền chủ) and developed in-depth knowledge of the Mekong Delta’s rice-growing geography. These factors enabled them to purchase grains at preferential rates by paying the farmers a small deposit (or advance) on an agreed collecting date with much lower contracted pricing.37 Once a harvest concluded, the farmers had to honour the contract and sell grains to the merchants before they were transported to rice mills in the city. As this cycle continued, the intermediary merchants and rice-mill owners made the most profits. The Vietnamese farmers found themselves hemmed in by hefty colonial taxes, the loans’ high interest rates, and lack of transparency in fluctuating market prices. Consequently, they had no choice but to keep selling their grains to the Chinese and taking Chinese loans to offset production costs in order to survive till the next harvest.38 H. L. Jammes, in Souvenir du Pays d’Annam, painted a vivid picture of the Chinese countryside agents’ operations:

The Chinese grain buyer settles, in the four arms of a river

on a comfortable boat, slinging a bag of piastres in one hand

and a game of baquan in the other, patiently waiting for the

customers, resting assured that the “fish will bite the bait”.

As soon as rice starts to turn yellow, Chinese agents march

through the villages, baiting the farmers by ringing his bags

of coins… The Chinese is then ready to offer his advances. If

the Annamite is unable to repay loans at maturity, the Chinese

will set a selling price for rice much lower than its real value.

Credit is, for the Chinese, a powerful means of exploiting the

Annamese farmers because they are always short of funds. They

have a compulsory expenditure every year: it is the payment of

their taxes. Chinese creditors are at their disposal to provide

such necessary funds. At the present, the harvest loans granted

to the native through provincial chiefs and guaranteed by the

government are only authorised to allow them, in the event

of a bad harvest, to pay the taxes in arrears. The paperwork

hinders farmers who often prefer to deal with Chinese creditors

despite the 12% monthly interest rate. This is a minimum rate,

recognised by the Annamese law and accepted by the French

Courts in Cochinchina. To dissolve of their debts, augmented

by these fabulous interests, the unfortunate Annamese peasants

must submit their property titles in place of securities that

constitute a mortgage in the hands of the creditor. If the

Annamese do not pay their debt, the Chinese will seize their

harvest at record-low pricing.39

The international shipping of rice, too, was handled predominantly by Chinese firms. Chinese rice mills in Hong Kong imported primarily Sài Gòn’s rice and further processed these grains to achieve a more standardised grading in line with Hong Kong’s importance as a global distributor. As Hong Kong and Sài Gòn–Chợ Lớn developed an interlinked “rice circuit”, there was no need for a standardised grading system to be developed in southern Vietnam, which significantly depressed the price of Sài Gòn’s rice on the global market and left local rice mills in Vietnam largely performing the function of mass production. Mass-produced rice meant that grain and rice-storage quality was often neglected in prevailing commercial approaches to shipping, which was reflected in the standard practice of “milling on arrival”.40 This inattention to quality, combined with the surprising absence of an established freight insurance industry in colonial Vietnam, shifted the burdens of taxes and economic losses to the importers rather than milling parties if unanticipated risks (usually shipwrecks) were to happen. Disregard for rice quality, and the absence of protection and a grade reference system were structured around one goal: “exporting as much rice as possible”, as Li Tana succinctly puts it.41 According to Ellen Tsao’s estimates, Chinese exports accounted for roughly 70 percent of the rice shipping business, serving the major markets of Hong Kong, Manila and Singapore. This left European firms a much smaller portion of market share, primarily dealing with France, the United States, Cuba and Japan.42

Chinese merchants, therefore, controlled the sources of grains, the rice mills that made the grains exportable, and the export networks.43 Pierre Brocheux describes their system as a “pyramid of dependency”, characterised by the creation of a usurious market dominated by Chinese and Indian moneylenders. This had come about in part because the colonial commercialisation of land and expensive infrastructural building diminished available credit for agricultural initiatives.44 The Bank of Indochina (Banque de l’Indochine) had been created by the colonial state to issue the colony’s currency and fund various developmental projects. But it was less interested in extending credit to small farmers, who made up the majority of the manufacturing workforce, than to the medium and large landowners, whose profits remained complicatedly attached to Chinese-oned rice mills in Chợ Lớn and the exploitation of Vietnamese farmers. The Bank, as Gerard Sasges and Scott Cheshier argue, served a crucial function that was “to leverage Chinese rather than French capital, diverting investment from Chinese enterprises and towards French”.45

The urbanisation of colonial Sài Gòn, in which the rice trade played a critical role, attracted Chinese and Vietnamese migrant labour from the countryside seeking economic opportunities. The colonial export economy and the thriving of the Mekong Delta trade reshaped the economic landscape of Sài Gòn in the early 20th century by initiating demand for jobs in production, transportation and service industries.46 As a result, as the population of the city grew exponentially, the number of Chinese in Chợ Lớn skyrocketed. By 1919, there were an estimated 101,427 Chinese in Chợ Lớn (accounting for about 37.3 percent of the total population of metropolitan Sài Gòn) – an almost 21 percent increase from 1907.47

Sài Gòn’s rapid transformation into a cosmopolitan hub with coexisting elements of interethnic interactions and economic modernity engendered problems of its own. Political dilemmas arose as a result of the Chinese merchants’ monopoly of the rice trade and junk networks, as Sài Gòn became the centre of colonial capital development. From the 1870s, the French radically reformulated their economic ideology and approach towards colonisation. Their turn to protectionism would collide with the business interests of the Chinese.

Chinese Domination of the Rice Trade, French Tariffs, and Transnational Networks in the 1880s

In the early 1870s, the system of Chinese rice commerce began to come into friction with the imperatives of a French colonial state ravenous for the enormous profits generated from rice exports and their tax revenues. This led to a protracted period of commercial rivalry, in which the French sought to gain authoritative control of the rice trade, whose monopolisation by the Chinese was deemed to be dangerously unregulated. On their part, the Chinese leaders – an increasingly powerful conglomeration made up of cosmopolitan capitalists and congrégation leaders – mounted strategic political opposition.48 These transformative encounters, which remained in the shadow of colonial politics and as a little-known story in Chinese community history, exposed the ill-conceived nature of French commercial policies and demonstrated Chinese merchants’ critical roles in reorienting the colonial approach to the transnational rice trade and the legal statuses of this community.

The rice export boom in Cochin-China drew much attention from French

and British colonists. In 1886, for example, exports rose to a record

3,480,500 tons, as demand from Hong Kong and Manila continued to rise;

a local observer reported that “there are no stocks at Chợ Lớn, grain being

shipped as fast as it arrives”.49 But it was chiefly the Chinese merchants who

were profiting from this boom. French observers lamented the successive

bankruptcies of European trading houses in Sài Gòn–Chợ Lớn and their

comparative disadvantages against Chinese-owned counterparts. On 10 June

1876, one such firm owned by German proprietors declared its foreclosure,

citing financial dissolution due to the lack of market price transparency

and Chinese dealers’ “disinclination to lower their prices in transactions”.50

Repeated complaints from European merchants about their inability to

have a fair competition with Chinese-owned trading houses in Chợ Lớn

preoccupied the Chamber of Commerce’s reports. The French colonial

government thus found itself trapped between seemingly contradictory

imperatives: policing Chinese rice merchants while sustaining the extant rice

networks and continuing to profit from them.

Gerard Sasges, in writing about the early period of French colonial rule, also highlights this troublesome start, attributing the underperformance of French enterprises to a combination of “incoherent economic policies” and “ideological confusion” as well as European merchants’ lack of practical local knowledge and funding.51 The central goal of the colonial state during this period, he asserts, was to generate revenue for its shrinking budget by diversifying from existing Chinese monopolies.52 Yet, diversification was no easy feat, if not virtually impossible, for a trade that accounted for more than 60 percent of total colonial exports. And in the words of Virginia Thompson, rice constituted “the sole product, the only article for both consumption and as a medium of exchange, the condition of the country’s prosperity, the keystone of Indochina’s economy”.53

In this entrenched commercial structure, Chinese merchants in Chợ Lớn and the Mekong Delta had established themselves not only as indispensable cooperators, business partners and taxpayers who enriched the colonial economy. They also served to link French Indochina’s regional commerce to the wider networks of East and Southeast Asian trade. The blossoming of Chợ Lớn’s rice milling industry turned this Chinese town into a central node where grains were transported to before being exported. It also enabled a small group of wealthy Chinese merchants to rise to the top of the social pyramid, including, for example, the Teochew Quách Đàm (郭琰 Guo Yan, also known as Kwek Siew Tee) and Vĩnh Sanh Chung, the Peranakan Hokkien Tjia Mah Yeh (謝媽延), and Jean-Baptiste Hui-Bon-Hoa (黃文華) and his family. These men and their business empires controlled most of the lucrative trade activities in Sài Gòn.

As Vương Hồng Sển depicts in his memoir of old Sài Gòn, while these prominent Chinese merchants engaged in the rice trade, they also branched out into industries such as real estate, construction and shipbuilding, extending their commercial influence and leaving their imprint on the urban landscape.54 Quách Đàm financed the construction of the principal market of Bình Tây with funding channelled largely from the success of his rice firm, Thông Hiệp, while Hui-Bon-Hoa’s company, Ogliastro, Hui Bon Hoa & Co., invested in real estate and dominated the moneylending business in the form of pawnshops.55

In particular, Quách Đàm, dubbed the “rice king of Cochinchina”, occupied an almost mythical place in the popular consciousness of Chợ Lớn. His wealth, political influence and civic contributions were so significant that the French colonial government awarded him the coveted Legion of Honour.56 At 14 years old, he had allegedly hidden himself in a steamship cabin, travelling from a derelict town in Chao’an county in eastern Guangdong across the Nanyang (South China Sea) to Sài Gòn in 1877. There, he took on all kinds of odd jobs to make ends meet: a coolie boy, junkyard bottle collector and food hawker. Despite the floating and irregular nature of these jobs, Quách Đàm saved enough money to make a foray into the rice business. Taking advantage of the economic opportunities brought about by French investment in the port of Sài Gòn–Chợ Lớn, he built the first Chinese-owned rice mills in the region, under the banner of his firm, Thông Hiệp (Yee Cheong), then located at Quai de Gaudot. According to some Chinese sources, by the early 20th century, Thông Hiệp managed to accumulate so much capital that he established four additional rice mills in Hong Kong, Singapore and Sài Gòn. These mills functioned cohesively within Quách Đàm’s transnational business network and generated up to 30,000 bales of rice a day, accounting for half of Vietnamese rice exports at the time.57 When he died in 1927, his elaborate funeral was attended by the city’s Chinese, Annamese and European elite. The cortège of “fifty luxurious cars” was preceded by a chariot flying a Franco-Chinese flag. Reporting on the proceedings, French journalist Georges Manue seized the opportunity to extol the benefits of colonial rule: “this is an example of what a Chinese can do when he lives under a solid government that guarantees him security and opportunities.”58 Posthumous celebrations of Quách Đàm’s legacy glorified his active investment in real estate and offshore properties, as well as his transformation of Chợ Lớn’s metropolitan area.59 A journalistic account indicated that Quách Đàm had shifted the centre of gravity of trade from Sài Gòn’s Arroyo Chinois to the Bình Tây market area in Chợ Lớn, and speculated that he had done so to overcome French regulations and to bring his family-run businesses under centralised control.60

The success stories of Chinese rice merchants in Cochinchina at the dawn of the 20th century share a similar narrative arc with those of the Chinese diaspora in other parts of Southeast Asia, including Bangkok, Singapore and Penang. For instance, the Wang Lee rice firm was founded by Tan Tsu Huang, who had arrived in Siam penniless but rose to prominence in the 1900s as the proprietor of two of Bangkok’s largest rice mills, with business networks stretching eastward to Hong Kong. Tan also operated junk and steamship services that dominated Siam’s early industry.61 In Penang, the “Big Five” – a Chinese conglomerate made up of the Tan, Yeoh, Lim, Cheah and Khoo families – accumulated enormous wealth in the 19th century through various ventures in the Straits Settlements, achieving a high degree of “regional economic ascendency”.62 As Yee Tuan Wong demonstrates, the Big Five and their associates put Penang’s rice imports largely under their control by successfully diverting a portion of Burma’s rice, then effectively monopolised by Indian rice traders, “to the southwestern Siamese states, North Sumatra, China, and Singapore, at much profit to themselves”.63

Living up to their reputation as transnational capitalists, Chinese merchants in Sài Gòn and other port cities operated in what was then known as a “Chinese rice circuit”. This involved a dynamic range of interport interactions, which defined the global nature of the rice milling and exporting businesses. Evidence from the historical newspapers archive at the National Library of Singapore suggests a close commercial relationship between Chinese merchants in Sài Gòn–Chợ Lớn and Singapore. Quách Đàm, for example, opened a branch of his firm Thông Hiệp at 80 Boat Quay, Singapore, to facilitate rice trading activities there. This information did not show up until 1923, when his British lawyer, Sir A. De Mello, posted a public notice in the British colonial press to announce the ownership transfer of his joint-stock company to a Singaporean Chinese merchant named Tan Eng Kwok.64

Faced with this Chinese-dominated political and economic landscape in Sài Gòn–Chợ Lớn, the French revamped their policing apparatus: they sought to implement a protective tariff on rice exports from Sài Gòn’s port and impose a heavy poll-tax on “registered” Chinese trading houses. The underlying motivation for these moves, besides the fear of Chinese domination of the commercial landscape, came from political pressure from European firms and lobby groups that wanted to be able to compete with Chinese businesses and were demanding a share of the profits from the lucrative Cochin-chinese trade.

The colonists’ urge to impose high tariffs on the rice trade (or private trade at large) must be contextualised within the broader framework of French imperial statecraft in the late 19th century. Irene Nørlund describes French economic policy starting in the 1880s as “one dominated by protectionism”.65 It entailed a systematic effort on the part of the colonial state not only to “raise protective tariffs against foreign rice in mother country, but also to reduce export duties in Cochinchina for rice going to France”.66 With the passing of a landmark general tariff law in 1892 known as the Méline Tariff, the French raised their tariffs on rice a total of eight times between 1879 and 1899; such repeated manipulations were meant to direct trade revenues towards France and to stifle the Chinese monopoly.67 As long-time participants in the Asian rice trade, the British followed French protectionist policies closely. Sir Alex Gentle, the secretary of the Singapore Chamber of Commerce, reported to the colonial secretary of the Settlements that additional French duties would have a prohibitory effect on Singapore– Sài Gòn trade, warning that “unless some modification or abatement can be procured, the flourishing trade between us will be destroyed”.68 Commenting on the newly introduced tariff, a British writer characterised French protectionism as myopic and impractical:

The protectionist feeling, so strong in France, shows itself

among the French colonists in French Cochinchina by

increasing antagonism to Chinese trade rivalry there. […]

The sore point is that Chinese acuteness and business aptitudes

have as successfully asserted themselves in Sài Gòn as in

other Far Eastern ports, and the French colonists cannot

brook alien swiftness thus winning in the commercial race

for wealth […] The commercial protection seems to lie in

keeping the Chinese in a subordinate position, and in not

allowing them to rise beyond certain bounds. Such a policy

runs counter to experience in this quarter of the world, where

the Chinese are found an indispensable factor in developing

backward countries. However, a French experiment, in trying

to do without any great Chinese aid in this respect, will prove

interesting. Its failure, we fancy, is foredoomed.69

With the unanimous adoption of the tariff increase in the Chamber of Commerce, the Chinese merchant community in Chợ Lớn began to feel the political pressure. On 30 December 1892, the heads of five congrégations – Canton, Fujian, Teochew, Hainan and Hakka – on behalf of Sài Gòn– Chợ Lớn’s Chinese trading houses, sent a letter to the governor-general of Cochinchina to voice their grievances. In it, they attacked the promulgation of the decree of 27 February 1892, which sought to enforce stringent regulations on Chinese trade by targeting the rice industry through tariffs and high taxation. The tariff, in their view, was an affront to Chinese commercial practices, with the potential of ruining the Chinese trade. They demanded a public hearing and hired a French-speaking legal advocate to contest the new regulation.70

Sensing the protectionist tide in the Sài Gòn Chamber of Commerce, Chinese leaders demanded to be heard by the Chamber leaders and asked for a decisive repeal of the said decree. They also demanded that the application of the decree be postponed until the date adopted by the Chinese traders for the liquidation of their annual operation, to allow trading houses in China to receive and request necessary information to settle their finances. On 3 March 1894, merchants of several trading houses delivered another petition, this time with a bold headline, “we have shown passive obedience by cooperating with French administrators most of the time, but in the present case concerning our commerce, we will not be silenced”.71 Citing commercial unrest in areas where Chinese capitalists had begun to refuse “any shipments of money or merchandise” relating to Sài Gòn as a form of protest, they opposed the additional exit duties on rice export as well as the forced registration of traders’ identities and declaration of business records, claiming that “the administration knows by the control, by the registers and by the patents that we have displayed at home and by the sign of our doors; to whom it deals and to whom it is to address by the payments of our taxes”.72 Most interestingly, they declared themselves the “victim of petty crimes” committed by their comrades, who were the “one rotten apple that spoils the barrels”.73 Unlike those small traders, they were major suppliers of the China trade and respected the rule of law. The Chinese leaders concluded: “We declare our intention to the greatest representative of the French in the Far East that businesses will be on a chokehold with the abrupt implementation of the increase in export duty, which requires further revision and reconsideration given the Chinese presence in Sài Gòn.”74

Chinese resistance took place not only in Chợ Lớn, but also in Hong Kong, which became a vigorous commercial battleground between the French authority and Chinese merchants based in Sài Gòn and Hong Kong. French members of the Chamber of Commerce were aiming to use the proposed tariff to also curb Sài Gòn’s Chinese dominance in the Hong Kong trade, where a rice milling industry was concomitantly developed – a process inextricably linked to Hong Kong’s escalating demand for Sài Gòn’s rice and Sài Gòn–Chợ Lớn’s Chinese merchant networks.75 This tariff gained traction in the chamber’s discussion on the grounds that since Chinese merchants enjoyed all the local advantages regardless of labour or freight costs as opposed to French merchants, the former had to comply with a comparable surtax so that the playing field could be levelled.76 On 16 March 1894, a representative from the French consulate in Hong Kong dispatched a message to Cochinchina, informing the governor-general of commercial stagnation in Hong Kong. The Chinese rice merchants based there refused to carry any merchandise to Sài Gòn, citing fear of high duties. As one merchant put it, “We prefer to pay a little more for the freight of rice and to buy the latter for ballast than to bow before the measure taken by the authorities of Indochina.”77

The reactions of Hong Kong’s Chinese rice merchants to the news of French tariffs were not surprising. The British port city had consistently been the number one destination for rice exports from Sài Gòn in the last few decades of the 19th century. In 1876, for example, a record 3,577,500 piculs of rice were exported to Hong Kong, followed distantly by 979,116 piculs to Surabaya, 444,730 piculs to Singapore, and 204,435 piculs to Batavia.78 Additionally, Hong Kong held a prominent place in the Sài Gòn–Nanyang trade both for the French colonial government’s strategic commercial expansion and for the Chinese rice merchants.79 On 26 January 1884, the French announced a subsidy for a new telegraphic line that would connect Sài Gòn with Tonkin and ultimately Hong Kong. “This new line of Saigon via Tongking to Hong Kong,” a report emphasised, “will operate independently of all control”, facilitating the intensifying trading relations in these areas.80

The Sài Gòn–Hong Kong rice trade had generated immense wealth and linked many Chinese merchants’ fortunes and privileged status in Hong Kong to their business operations in Sài Gòn. Chinese rice mills in Chợ Lớn often functioned as productive branches within a complicated web of Chinese commercial conglomerates based in Hong Kong and elsewhere.

More importantly, they coexisted and came in direct competition with European trading houses, and shared a stake within the transnational rice trade across the Nanyang. Tjia Mah Yeh (Tạ Mã Điền), who founded two of Chợ Lớn’s most prominent rice mills (the aforementioned Ban Hong Guan and Ban Tek Guan), took advantage of the Hong Kong connections to establish a steamship company, The Hock Hai Steamship Co. (福海), in that port. This enabled him to engage in commercial activities across Hong Kong, Shanghai, Japan and further south in the Nanyang, including Singapore, Batavia and the Philippines.81

Given this intimate commercial connection with Hong Kong and the vast networks of capital and interpersonal relationships required for the rice mill business, French attempts to undermine Chinese commercial strength were not well received by the large merchant communities in Sài Gòn–Chợ Lớn. In fact, the Chinese protests was so intense and far-reaching that it bewildered the colonial administrators. M. Aug Boudin, the General Procurer and the Chief of the Judiciary Service of Indochina, exclaimed that “out of all the Asian traders in the colony, the Indian representatives had willingly complied to the decree without any difficulty; it is quite hard to understand how it is only in Sài Gòn–Chợ Lớn that the resistance occurred with such ensemble and much energy”.82

By the late 1890s, rice crops in Cochinchina experienced a short-lived depression. Exacerbated by continued protests against the French tariff, rice businesses almost ceased for the entire October in 1892. Chinese and, to a lesser extent, Indian merchants tirelessly petitioned the French Chamber of Commerce, arguing that it was not only the insurmountable burden of taxes that would be detrimental to their businesses but also the “inevitable fines” as a consequence of mindless formality violation.83 In the face of unceasing opposition from Chinese merchants in Sài Gòn–Chợ Lớn and those abroad in the port of British Hong Kong, the French Chamber of Commerce shot down the implementation of the decree at the end of 1899. Aug Boudin then confessed that this decree and its multiple propositions had caused overwhelming indignation among the Chinese population in Chợ Lớn. With a mix of concession and ambiguity, he promised that “a new examination would be made then to propose to the chamber a new text, which while taking into account the legitimate claims of the Chinese, would also safeguard the interests of Europeans”. He then concluded that “it seems to me that this solution would be a preferable one…In any case, until further notice, I order the prosecutions to suspend any proceedings.”84

Conclusion

Sài Gòn–Chợ Lớn was, and has been, undoubtedly a commercial city. Su Lin Lewis, the author of a comparative history of Penang, Bangkok and Rangoon, aptly describes these three Southeast Asian port cities as having “emerged together out of the winds of commerce, following a lineage of cosmopolitan urban life in Southeast Asia that dates back hundreds of years”.85 They were participants in a long-established premodern trading emporium that constituted what Anthony Reid has dubbed the Southeast Asian “Age of Commerce” – the heyday of interregional maritime trade. Sài Gòn–Chợ Lớn’s development was inextricably linked to commercial activities within this close-knit network of Southeast Asian port cities, and its urban histories reflect this fact.86

At the centre of these historical developments stood Chinese migrant communities and their commercial networks, which helped transform southern Vietnam into a stronghold of French economic interests in Southeast Asia. In addition to providing a foundation for the colonial extraction of profits, the Chinese rice trade thrust Sài Gòn into the sphere of global capitalism. It tested the limits of French economic policies, which relied heavily on revenue generated from a Chinese-dominated trade and an ideological imperative to make Cochinchina a self-sufficient part of the empire independent of the metropolitan budget. French protectionism sought to intercept transnational Chinese rice networks and bring them under centralised colonial control. But even as it subjected Chinese merchants to French administrative formalities, modern standards of transparency and systematic registrations, it ultimately still failed to force the Chinese migrants into becoming, as one colonist put it, “lawful subject[s] of the colonial state”.87

Acknowledgements

I am thankful to Haydon Cherry of Northwestern University for his detailed feedback and suggestions on the draft of this article. The staff at the National Library of Singapore – especially Joanna Tan and Ang Seow Leng – provided indispensable assistance in locating rare materials during my Lee Kong Chian Fellowship tenure. I also want to thank Lee Chor Lin for helping me decipher difficult Chinese texts on a few occasions and for the company during my stay in Singapore.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Primary Sources

Bouchot, Jean. Documents pour servir à l’histoire de Sài Gòn, 1859–1865. Sài Gòn: Albert Portail, 1927.

“Chinese Merchants Petitioned to the Governor-General of Cochinchina Regarding the Decree of 27 January 1892.” GOUCOCH L.0 N5522, TTLTQG-II, HCMC, 3 March 1894.

Công Luận Báo [L’Opinion]. “Chợ Mới Bình-Tây, Đại Kỳ Mưu Của Quách Đàm” [The new market of Bình Tây, Quách Đàm’s strategic plot]. TVQGVN, Hanoi, 13 September 1928.

Coquerel, Albert. Paddys et Riz de Cochinchine. Lyon: A. Rey, 1911.

“Dispatche, Consulat de France à Hong Kong.” GOUCOCH L.0 N5522, TTLTQG-II, HCMC, 16 March 1894.

Dubreuil, Robert. “De la Condition des Chinois et de leur Rôle Economique en Indochine.” PhD diss., University of Paris, 1910.

Gentle, Alex. Alex Gentle, Secretary of the Singapore Chamber of Commerce, to the Colonial Secretary of the Straits Settlements. Singapore Chamber of Commerce Annual Report, 1887–1894, National Archives of Singapore (microfilm NA3347).

Gouvernement Général de l’Indochine. Exposition Coloniale Internationale. Paris: Indochine Française, 1931.

郭琰近代越南潮商 “Guo Yan: Jindai yuenan chao shang” [Quách Đàm: Vietnam’s Chaozhou merchant]. Accessed 15 December 2019.

Jammes, H. L. Souvenir du Pays d’Annam. Paris: A. Challamel, 1900.

La Revue Economique d’Extrême-Orient. “Echos de Indochine, Cochinchine.” 5 March 1926, 77.

“Letter from the Chinese Congregations of Chợ Lớn.” GOUCOCH L.0 N5522, Dossier Relatif à la Règlementation du Commerce Chinois et Activités des Congrégations Asiatiques, Années 1890–1894 [Files related to the regulations of Chinese commercial activities and Asian congregations, 1890–1894], TTLTQG-II, HCMC, 30 December 1892.

“M. Holbe, Vice-Président de la Chambre de Commerce à Monsieur le Gouverner de la Cochinchine.” GOUCOCH L.13 N5554, TTLTQG-II, HCMC, March 1894.

“M. Rolland Président de la Chambre de Commerce à Monsieur le Lieutenant-Gouverneur de la Cochinchine.” GOUCOCH L.13 N5554, TTLTQG-II, HCMC, 20 July 1893.

Manue, George L. R. “Le Buddha de le Richesse” [The Buddha of wealth]. Le Journal en Indochine (18 July 1927).

Meeting of the Sài Gòn Chamber of Commerce. Session 321, GOUCOCH L.0 N5522, TTLTQG-II, HCMC, 29 December 1893.

Nguyễn, Đức Hiệp. Sài Gòn Chợ Lớn: Qua Những Tư Liệu Quý Trước 1945 [Sài Gòn– Chợ Lớn: Pre-1945 rare documents]. T.P. Hồ Chí Minh: Nhà Xuất Bản Văn Hoá-Văn Nghệ, 2016.

Nguyễn, Văn Nghi. Etudes Economique sur la Cochinchine Française. Montpellier: Impr. Firmin et Montane, 1920.

North-China Herald and Supreme Court & Consular Gazette (1870–1941). “Sài Gòn.” 10 June 1876.

—. “The Parts of the East: The Frenchman’s Home in Sài Gòn.” 16 August 1919.

Postel, Raoul. A Travers la Cochinchine. Paris: Challamel Aine, 1887.

“Rapport Au Gouverneur-General.” GOUCOCH L.0 N5522, TTLTQG-II, HCMC, 27 February 1892.

“Récapitulation du Riz par Pays” [Summary of rice export by countries]. Annuaire de la Cochinchine Française, BnF Gallica (1876): 221.

Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser. “The Trade of Saigon.” 8 July 1892, 3. (From NewspaperSG)

—. “A Fine Electrical Installation at Cholon.” 16 January 1907, 6. (From NewspaperSG)

—. “Page 5 Advertisements Column 4: Notice,” 24 April 1923, 5. (From NewspaperSG)

—.Straits Times. “Protection against Chinese.” 18 March 1896, 2. (From NewspaperSG)

—. “La Vie Saigonnaise.” 18 June 1902, 2. (From NewspaperSG)

—. “Rice Mill Electric Installation.” 15 January 1907, 7. (From NewspaperSG)

—. “Progressive Saigon.” 20 January 1909, 7. (From NewspaperSG)

—.Straits Times Weekly Issue. “The Saigon-Tonquin-Hong Kong Cable.” 26 January 1884, 3. (From NewspaperSG)

—. “The Saigon Rice Market.” 6 May 1886, 4. (From NewspaperSG)

—. “Suspension of Decree Due to Chinese Resistance.” GOUCOCH L.0 N5522, TTLTQG-II, HCMC, 8 March 1894.

Trịnh, Hoài Đức. Gia Định Thông Chí, Histoire et Description de La Basse Cochinchine (Pays de Gia Định) [A history and descriptions of the Lower Mekong regions (Gia Định province)]. Paris: Imprimerie Imperiale, 1864.

Vương, Hồng Sển. Sài Gòn Năm Xưa [Sài Gòn, past and present]. T.P. HồChíMinh: NhàXuất Bản Tổng Hợp Thành Phố HồChíMinh, 2018.

Secondary Sources

Barrett, Tracy C. The Chinese Diaspora in South-East Asia: The Overseas Chinese in IndoChina. Library of China Studies. London: Tauris, 2012. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 305.8951059 BAR)

Barton, Clifton Gilbert. “Credit and Commercial Control: Strategies and Methods of Chinese Businessmen in South Vietnam.” PhD diss., Cornell University, 1977.

Brocheux, Pierre. The Mekong Delta: Ecology, Economy, and Revolution, 1860–1960. Monograph 12. Madison: Center for Southeast Asian Studies, University of Wisconsin- Madison, 1995. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSEA 330.9597 BRO)

Cherry, Haydon. “Down and Out in Sài Gòn: A Social History of the Poor in a Colonial City, 1860–1940.” PhD diss., Yale University, 2011.

—. Down and Out in Saigon: Stories of the Poor in a Colonial City. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2019. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSEA 305.5690597 CHE)

Choi, Byung Wook. Southern Vietnam under the Reign of Minh Mạng (1820–1841): Central Policies and Local Response. Southeast Asia Program Series, no. 20. Ithaca, NY: Southeast Asia Program Publications, Southeast Asia Program, Cornell University, 2004.

Cooke, Nola and Li Tana, eds. Water Frontier: Commerce and the Chinese in the Lower Mekong Region, 1750–1880. World Social Change. Singapore: Singapore University Press; Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2004. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 380.10899510597 WAT)

Dutton, George. The Tây Son Uprising: Society and Rebellion in Eighteenth-Century Vietnam. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2006. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSEA 959.703 DUT)

Engelbert, Thomas. “Chinese Politics in Colonial Saigon: The Case of the Guomindang.” Chinese Southern Diaspora Studies 4 (2010): 93–116.

Goscha, Christopher. The Penguin History of Modern Vietnam. London: Allen Lane, 2016. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSEA 959.7 GOS)

Gunn, Geoffrey C. Rice Wars in Colonial Vietnam: The Great Famine and the Viet Minh Road to Power. Asia/Pacific/Perspectives. Plymouth: Rowman & Littlefield, 2014. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSEA 959.704 GUN)

Hamilton, Gary G., ed. Cosmopolitan Capitalists: Hong Kong and the Chinese Diaspora at the End of the 20th Century. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1999. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RBUS 330.9512506 COS)

Latham, A. J. H. “From Competition to Constraint: The International Rice Trade in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries.” Business and Economic History 17 (1988): 91–102. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website)

Latham, A. J. H. and Larry Neal. “The International Market in Rice and Wheat, 1868–1914.” Economic History Review 36, no. 2 (1983): 260–80. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website)

Lê, Thị Vỹ Phượng. “Người Minh Hương, Dấu Ấn Di Dân và Việt Hóa Qua Một SốTư Liệu Hán Nôm” [Minh Hương: A history of immigration and Vietnamisation through selected Sino-Vietnamese documentations]. Tạp Chí Khoa Học Xã Hội [Journal of social science research] 7, no. 179 (2013): 66–73.

Lee, Seung-Joon. Gourmets in the Land of Famine: The Culture and Politics of Rice in Modern Canton. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2011. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RBUS 338.173180951275 LEE)

—. “Rice and Maritime Modernity: The Modern Chinese State and the South China Sea Rice Trade.” In Rice: Global Networks and New Histories, edited by Francesca Bray et al., 99–117. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015.

Lewis, Su Lin. Cities in Motion: Urban Life and Cosmopolitanism in Southeast Asia, 1920– 1940. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSEA 307.7609590904 LEW)

Li, Tana. Nguyễn Cochinchina: Southern Vietnam in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries. Ithaca, NY: Southeast Asia Program Publications, 1998.

—. “Rice Trade in the 18th and 19th Century Mekong Delta and Its Implications.” In Thailand and Her Neighbors (II): Laos, Vietnam and Cambodia, edited by Thanet Arpornsuwan, 198–214. Bangkok: Thammasat University Press, 1995.

—. “Saigon’s Rice Export and Chinese Rice Merchants from Hong Kong, 1870s–1920s.” In Vietnam’s Ethnic and Religious Minorities: A Historical Perspective, edited by Thomas Engelbert, 33–52. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang, 2016.

—. “The Chinese in Vietnam.” In The Encyclopedia of the Chinese Overseas, edited by Lynn Pan and Chinese Heritage Centre (Singapore), 228–33. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1999.

Nguyễn, Cẩm Thuỷ. Định cư của người Hoa trên đất Nam Bộ: từ thế kỷ XVII đến năm 1945 [Chinese settlement in Southern Vietnam: From the seventeenth century to 1945]. Hà Nội: Khoa Học Xã Hội, 2000.

Nguyễn, Phan Quang. Góp thêm tư liệu Sài Gòn-Gia Định, 1859–1945 [Further contribution to Sài Gòn-Gia Định documentation, 1859–1945]. T.P. Hồ Chí Minh: Nhà Xuất Bản Trẻ, 1998.

Nguyễn, Thế Anh. Kinh Tế và Xã Hội Việt Nam dưới Các Vua Triều Nguyễn [The Vietnamese economy and society under the Nguyễn King]. Saigon: Lửa Thiêng, 1968.

—. “L’immigration chinoise et la colonisation du delta du Mékong.” Vietnam Review 1 (Autumn–Winter 1996): 154–77.

Norlund, Irene. The French Empire: The Colonial State in Vietnam and the Economic Policy 1885–1940. Copenhagen: University of Copenhagen Press, 1989. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSEA 338.9597 NRL)

Owen, Norman G. “The Rice Industry in Mainland Southeast Asia.” Journal of Siam Society 59, pt. 2 (July 1971): 75–143.

Reid, Anthony. Southeast Asia in the Age of Commerce, 1450–1680. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1988. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSEA 959 REI)

Salmon, Claudine and Tạ Trọng Hiệp. “Wang Annan Riji: A Hokkien Literatus Visits Saigon (1890).” Chinese Southern Diaspora Studies 4 (2010): 74–88.

Sasges, Gerard. “Scaling the Commanding Heights: The Colonial Conglomerates and the Changing Political Economy of French Indochina.” Modern Asian Studies 49, no. 5 (September 2015): 1485–1525. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website)

Sasges, Gerard and Scott Cheshier. “Competing Legacies: Rupture and Continuity in Vietnamese Political Economy.” South East Asia Research 20, no. 1 (2012): 5–33. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website)

Sinn, Elizabeth. Between East and West: Aspects of Social and Political Development in Hong Kong. Hong Kong: Centre of Asian Studies, University of Hong Kong, 1996.

Sơn, Nam. Đất Gia Định Xưa [A history of Gia Định]. T.P. Hồ Chí Minh: Nhà Xuất Bản Thành PhốHồ Chí Minh, 1984.

Trần, Khánh. Người Hoa trong Xã Hội Việt Nam: Thời Pháp Thuộc và dưới Chế Độ Sài Gòn [Ethnic Chinese in Vietnamese society: Under French domination and the Sài Gòn regime]. Hà Nội: Nhà Xuất Bản Khoa Học Xã Hội, 2002.

Tsao, Ellen. “Chinese Rice Millers and Merchants in French Indochina.” Chinese Economic Journal 6 (December 1932): 450–63.

Wheeler, Charles. “Interests, Institutions, and Identity: Strategic Adaptation and the Ethno-evolution of Minh Hương (Central Vietnam), 16th–19th Centuries.” Itinerario 39 (April 2015): 141–66.

Wong, Yee Tuan. Penang Chinese Commerce in the 19th Century: The Rise and Fall of the Big Five. Singapore: ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute, 2015. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSEA 338.7095951 WON)

—. “The Big Five Hokkien Families in Penang, 1830s–1890s.” Chinese Southern Diaspora Studies 1 (2007): 106–15.

NOTES

-

Li Tana, “Rice Trade in the 18th and 19th Century Mekong Delta and Its Implications,” in Thailand and Her Neighbors (II): Laos, Vietnam and Cambodia, ed. Thanet Arpornsuwan (Bangkok: Thammasat University Press, 1995), 198–214. For a relevant precolonial history that offers important insights into the making of the Chinese trade, see also Li Tana, Nguyễn Cochinchina: Southern Vietnam in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries (Ithaca, NY: Southeast Asia Program Publications, 1998). For a social history of Sài Gòn and the impact of the rice trade on its residents’ livelihoods, see Haydon Cherry, Down and Out in Saigon: Stories of the Poor in a Colonial City (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2019). (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSEA 305.5690597 CHE) ↩

-

Christopher Goscha, The Penguin History of Modern Vietnam (London: Allen Lane, 2016), 162. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSEA 959.7 GOS) ↩

-

Li Tana, “The Chinese in Vietnam,” in The Encyclopedia of the Chinese Overseas, ed. Lynn Pan and Chinese Heritage Centre (Singapore) (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1999), 228. ↩

-

Charles Wheeler, “Interests, Institutions, and Identity: Strategic Adaptation and the Ethno-evolution of Minh Hương (Central Vietnam), 16th–19th Centuries,” Itinerario 39 (April 2015): 142–43. ↩

-

Lê Thị Vỹ Phượng, “Người Minh Hương, Dấu Ấn Di Dân và Việt Hóa Qua Một Số Tư Liệu Hán Nôm” [Minh Hương: A history of immigration and Vietnamisation through selected Sino-Vietnamese documentations]. Tạp Chí Khoa Học Xã Hội [Journal of social science research] 7, no. 179 (2013): 66–67. ↩

-

Trịnh Hoài Đức, Gia Định Thông Chí, Histoire et Description de La Basse Cochinchine (Pays de Gia Định) [A history and descriptions of the Lower Mekong regions (Gia Định province)] (Paris: Imprimerie Imperiale, 1864), 10–18. ↩

-

For details, see George Dutton, The Tây Son Uprising: Society and Rebellion in Eighteenth-Century Vietnam (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2006). (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSEA 959.703 DUT) ↩

-

Dutton, Tây Son Uprising, 32. ↩

-

Robert Dubreuil, “De la Condition des Chinois et de leur Rôle Economique en Indochine” (PhD diss., University of Paris, 1910), 12. ↩

-

Choi Byung Wook, Southern Vietnam under the Reign of Minh Mạng (1820–1841): Central Policies and Local Response, Southeast Asia Program Series, no. 20 (Ithaca, NY: Southeast Asia Program Publications, Southeast Asia Program, Cornell University, 2004), 147. ↩

-

Nguyễn Thế Anh, Kinh Tế và Xã Hội Việt Nam dưới Các Vua Triều Nguyễn [The Vietnamese economy and society under the Nguyễn King] (Saigon: Lửa Thiêng, 1968), 42–50. ↩

-

Nguyễn Thế Anh, “L’immigration chinoise et la colonisation du delta du Mékong,” Vietnam Review 1 (Autumn–Winter 1996): 154–77. ↩

-

Tracy C. Barrett, The Chinese Diaspora in South-East Asia: The Overseas Chinese in IndoChina, Library of China Studies (London: Tauris, 2012), 13–14. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 305.8951059 BAR) ↩

-

Barrett, Chinese Diaspora, 23. ↩

-

Li, “Chinese in Vietnam,” 1999. ↩

-

Li, “Chinese in Vietnam,” 1999. ↩

-

Thomas Engelbert, “Chinese Politics in Colonial Saigon: The Case of the Guomindang,” Chinese Southern Diaspora Studies 4 (2010): 96. Other notable works that highlight the making of Sài Gòn–Chợ Lớn as the centre of rice commerce in southern Vietnam include Nola Cooke and Li Tana, eds., Water Frontier: Commerce and the Chinese in the Lower Mekong Region, 1750–1880, World Social Change (Singapore: Singapore University Press; Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2004). (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 380.10899510597 WAT) Specifically on the importance of the Mekong Delta rice trade, see Sơn Nam, Đất Gia Định Xưa [A history of Gia Định] (T.P. Hồ Chí Minh: Nhà Xuất Bản Thành Phố Hồ Chí Minh, 1984); Li Tana, “Rice Trade in the 18th and 19th Century Mekong Delta,” 198–214. ↩

-

See Raoul Postel, A Travers la Cochinchine (Paris: Challamel Aine, 1887), 80–99; Jean Bouchot, Documents pour servir à l’histoire de Sài Gòn, 1859–1865 (Sài Gòn: Albert Portail, 1927). ↩

-

“The Parts of the East: The Frenchman’s Home in Sài Gòn,” North-China Herald and Supreme Court & Consular Gazette (1870–1941), 16 August 1919. ↩

-

A. J. H. Latham, “From Competition to Constraint: The International Rice Trade in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries,” Business and Economic History 17 (1988): 92. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

Such positive views of modernised Sài Gòn could be found in the rare accounts of itinerant Chinese merchants on their visits to the city to establish business connections in the 1880s. A Hokkien merchant, Tan Siu Eng (陳琇榮) from Batavia, described the “harmonisation of French rule”, which made Sài Gòn by no means inferior to Singapore or Hong Kong. See Claudine Salmon and Tạ Trọng Hiệp, “Wang Annan Riji: A Hokkien Literatus Visits Saigon (1890),” Chinese Southern Diaspora Studies 4 (2010): 74–88. ↩

-

“Progressive Saigon,” Straits Times, 20 January 1909, 7, (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“La Vie Saigonnaise,” Straits Times, 18 June 1902, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Gouvernement Général de l’Indochine, Exposition Coloniale Internationale (Paris: Indochine Française, 1931), 31–32. ↩

-

A. J. H. Latham and Larry Neal, “The International Market in Rice and Wheat, 1868–1914,” Economic History Review 36, no. 2 (1983): 262. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

Haydon Cherry, “Down and Out in Sài Gòn: A Social History of the Poor in a Colonial City, 1860–1940” (PhD diss., Yale University, 2011), 31–35. ↩

-

Albert Coquerel, Paddys et Riz de Cochinchine (Lyon: A. Rey, 1911), appendix, tables VIII, IX. ↩

-

Nguyễn Phan Quang, Góp thêm tư liệu Sài Gòn-Gia Định, 1859–1945 [Further contribution to Sài Gòn-Gia Định documentation, 1859–1945] (T.P. Hồ Chí Minh: Nhà Xuất Bản Trẻ, 1998), 15–19. ↩

-

Engelbert, “Chinese Politics in Colonial Saigon,” 98. ↩

-

Clifton Gilbert Barton, “Credit and Commercial Control: Strategies and Methods of Chinese Businessmen in South Vietnam” (PhD diss., Cornell University, 1977). ↩

-

Barton, “Credit and Commercial Control,” 85. ↩

-

Trần Khánh, Người Hoa trong Xã Hội Việt Nam: Thời Pháp Thuộc và dưới Chế Độ Sài Gòn [Ethnic Chinese in Vietnamese society: Under French domination and the Sài Gòn regime] (Hà Nội: Nhà Xuất Bản Khoa Học Xã Hội, 2002), 217. ↩

-

“Rice Mill Electric Installation,” Straits Times, 15 January 1907, 7. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“A Fine Electrical Installation at Cholon,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 16 January 1907. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Sơn Nam, Đất Gia Định Xưa,120. ↩

-

Trần Khánh, Người Hoa trong Xã Hội Việt Nam, 219. ↩

-

Nguyễn Văn Nghi, Etudes Economique sur la Cochinchine Française (Montpellier: Impr. Firmin et Montane, 1920), 53–54. ↩

-

Scholars have elaborated on the Vietnamese farmers’ uninformed decisions to engage in grain sales with Chinese rice dealers as the consequence of Chinese monopoly. During the colonial period, many Chinese brokers concealed market prices, as a widespread practice, only to publicly declare them right before or after a principal market was closed. This left farmers even more vulnerable to the unpredictability of price oscillations. The French colonial government was fully aware of this profit-extracting “malpractice”; on occasion they attempted to crack down on it, by taking advantage of modern telegraphic technology to send pricing information to the chiefs of towns, where it was mandatorily posted in the marketplace. However, many Chinese preempted this move, using their personal connections with these chiefs or the local farmers to convince them to sell grains early. For the most extensive treatment of this point, see the chapter “The Monoculture of Rice” in Pierre Brocheux, The Mekong Delta: Ecology, Economy, and Revolution, 1860–1960, Monograph 12 (Madison: Center for Southeast Asian Studies, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 1995), 67. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSEA 330.9597 BRO) ↩

-

H. L. Jammes, Souvenir du Pays d’Annam (Paris: A. Challamel, 1900). ↩

-

“M. Rolland Président de la Chambre de Commerce à Monsieur le Lieutenant-Gouverneur de la Cochinchine,” GOUCOCH L.13 N5554, TTLTQG-II, HCMC, 20 July 1893. “Milling on arrival” was a method often practised by Chinese millers in Sài Gòn–Chợ Lớn wherein even though a rice order had been made by a corporate client, millers would not start processing rice until export ships arrived in Chợ Lớn in order to cut storage costs, oftentimes resulting in less refined, low-quality grains. ↩

-

Li Tana, “Saigon’s Rice Export and Chinese Rice Merchants from Hong Kong, 1870s–1920s,” in Vietnam’s Ethnic and Religious Minorities: A Historical Perspective, ed. Thomas Engelbert (Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang, 2016), 33. ↩

-

Ellen Tsao, “Chinese Rice Millers and Merchants in French Indochina,” Chinese Economic Journal 6 (December 1932): 460–61. ↩

-

Nguyễn Đức Hiệp, Sài Gòn Chợ Lớn: Qua Những Tư Liệu Quý Trước 1945 [Sài Gòn–Chợ Lớn: Pre-1945 rare documents] (T.P. Hồ Chí Minh: Nhà Xuất Bản Văn Hoá-Văn Nghệ, 2016), 299. ↩

-

Brocheux, The Mekong Delta, 70. ↩

-

Gerard Sasges and Scott Cheshier, “Competing Legacies: Rupture and Continuity in Vietnamese Political Economy,” South East Asia Research 20, no. 1 (2012): 16. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

Nguyễn Cẩm Thuỷ, Định cư của người Hoa trên đất Nam Bộ: từ thế kỷ XVII đến năm 1945 [Chinese settlement in Southern Vietnam: From the seventeenth century to 1945] (Hà Nội: Khoa Học Xã Hội, 2000), 36–37. ↩

-

Nguyễn Phan Quang, Sài Gòn-Gia Định, 50–51. ↩

-

Gary G. Hamilton, ed., Cosmopolitan Capitalists: Hong Kong and the Chinese Diaspora at the End of the 20th Century (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1999). (From National Library Singapore, call no. RBUS 330.9512506 COS) ↩

-

“The Saigon Rice Market,” Straits Times Weekly Issue, 6 May 1886, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Sài Gòn,” North-China Herald and Supreme Court & Consular Gazette (1870–1941), 10 June 1876. ↩

-

Gerard Sasges, “Scaling the Commanding Heights: The Colonial Conglomerates and the Changing Political Economy of French Indochina,” Modern Asian Studies 49, no. 5 (September 2015): 1490. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

Sasges, “Scaling the Commanding Heights,” 1493. ↩

-

Geoffrey C. Gunn, Rice Wars in Colonial Vietnam: The Great Famine and the Viet Minh Road to Power, Asia/Pacific/ Perspectives (Plymouth: Rowman & Littlefield, 2014), 11. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSEA 959.704 GUN) ↩

-

Vương Hồng Sển, Sài Gòn Năm Xưa [Sài Gòn, past and present] (T.P. HồChíMinh: NhàXuất Bản Tổng Hợp Thành PhốHồChíMinh, 2018). ↩

-

Engelbert, “Chinese Politics in Colonial Saigon,” 96–97. ↩

-

“Echos de Indochine, Cochinchine,” La Revue Economique d’Extrême-Orient, 5 March 1926, 77. ↩

-

郭琰近代越南潮商 “Guo Yan: Jindai yuenan chao shang” [Quách Đàm: Vietnam’s Chaozhou merchant], accessed 15 December 2019.. ↩

-

Georges L. R. Manue, “Le Buddha de la Richesse” [The Buddha of wealth], Le Journal en Indochine (18 July 1927). ↩

-

郭琰近代越南潮商. His other businesses included rice mills in Hong Kong and Singapore, a sugar factory in Cambodia, and freight companies providing services between Shantou and Sài Gòn. ↩

-

“Chợ Mới Bình-Tây, Đại Kỳ Mưu Của Quách Đàm” [The new market of Bình Tây, Quách Đàm’s strategic plot], Công Luận Báo [L’Opinion], TVQGVN, Hanoi, 13 September 1928. See also Vương Cẩm Tú, Sài Gòn Xưa & Nay, 15. ↩

-

Lee Seung-Joon, “Rice and Maritime Modernity: The Modern Chinese State and the South China Sea Rice Trade,” in Rice: Global Networks and New Histories, ed. Francesca Bray et al. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015), 111. ↩

-

Wong Yee Tuan, “The Big Five Hokkien Families in Penang, 1830s–1890s,” Chinese Southern Diaspora Studies 1 (2007): 106. ↩

-

Wong, “Big Five,” 111. For the most comprehensive study of the Penang’s Big Five, see Wong Yee Tuan, Penang Chinese Commerce in the 19th Century: The Rise and Fall of the Big Five (Singapore: ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute, 2015). (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSEA 338.7095951 WON) ↩

-

“Page 5 Advertisements Column 4: Notice,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 24 April 1923, 5. (From NewspaperSG). No specific reasons were given for the transfer, but it could be deduced from Georges Manue’s account that Quách Đàm was gravely sick around this time and consequently bedridden. Coupled with a struggling rice market in the post-1919 Southeast Asian rice crisis, this business decision seemed to be a downsizing initiative to lessen the financial risks for his larger firm in Chợ Lớn. ↩

-

Irene Nørlund, The French Empire: The Colonial State in Vietnam and the Economic Policy 1885–1940 (Copenhagen: University of Copenhagen Press, 1989), 73. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSEA 338.9597 NRL) ↩

-

Norman G. Owen, “The Rice Industry in Mainland Southeast Asia,” Journal of Siam Society 59, pt. 2 (July 1971): 113. ↩

-

Owen, “Rice Industry,” 113. ↩

-

Alex Gentle, Secretary of the Singapore Chamber of Commerce, to the Colonial Secretary of the Straits Settlements, Singapore Chamber of Commerce Annual Report, 1887–1894, National Archives of Singapore (microfilm NA3347). The correspondence is regarding differential duties on Singapore’s export goods to Sài Gòn imposed by the French. ↩

-

“Protection against Chinese,” Straits Times, 18 March 1896, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Letter from the Chinese Congregations of Chợ Lớn,” GOUCOCH L.0 N5522, Dossier Relatif à la Règlementation du Commerce Chinois et Activités des Congrégations Asiatiques, Années 1890–1894 [Files related to the regulations of Chinese commercial activities and Asian congregations, 1890–1894], TTLTQG-II, HCMC, 30 December 1892. ↩

-

“Chinese Merchants Petitioned to the Governor-General of Cochinchina Regarding the Decree of 27 January 1892,” GOUCOCH L.0 N5522, TTLTQG-II, HCMC, 3 March 1894. ↩

-

“Chinese Merchants Petitioned.” ↩

-

“Chinese Merchants Petitioned.” ↩

-

“Chinese Merchants Petitioned.” ↩

-

Hong Kong’s demand for Sài Gòn’s rice increased exponentially since the mid-19th century. This was due not only to the forced opening of this port by British free trade imperialism in the aftermath of the Opium Wars, but also to the frequency of rice shortages in Chinese port cities such as Hong Kong and Canton, which culminated in a series of food riots. As a cheaper alternative – owing to the lack of grading and quality control – rice from Sài Gòn became an affordable solution to existing socioeconomic problems in China’s port cities. For a more detailed treatment of this history, see Lee Seung-Joon, Gourmets in the Land of Famine: The Culture and Politics of Rice in Modern Canton (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2011) (From National Library Singapore, call no. RBUS 338.173180951275 LEE); Elizabeth Sinn, Between East and West: Aspects of Social and Political Development in Hong Kong (Hong Kong: Centre of Asian Studies, University of Hong Kong, 1996) ↩

-

“M. Holbe, Vice-Président de la Chambre de Commerce à Monsieur le Gouverner de la Cochinchine,” GOUCOCH L.13 N5554, TTLTQG-II, HCMC, March 1894. ↩

-

“Dispatche, Consulat de France à Hong Kong,” GOUCOCH L.0 N5522, TTLTQG-II, HCMC, 16 March 1894. Li Tana also indicates that under the pressure of newly introduced French tariffs, paddy exports dropped from 165,000 tons in 1891 to 72,000 tons in 1896. See Li, “Sài Gòn’s Rice Export,” 39. ↩

-

Récapitulation du Riz par Pays” [Summary of rice export by countries], Annuaire de la Cochinchine Française, BnF Gallica (1876): 221. A picul is roughly equivalent to 60.479 kg. ↩

-

Cherry, Down and Out in Sài Gòn, 27–28. ↩

-

“The Saigon-Tonquin-Hong Kong Cable,” Straits Times Weekly Issue, 26 January 1884, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Li, “Sài Gòn’s Rice Export,” 33–52. ↩

-

“Rapport Au Gouverneur-General,” GOUCOCH L.0 N5522, TTLTQG-II, HCMC, 27 February 1892. ↩

-

“The Trade of Saigon,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 8 July 1892, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Suspension of Decree Due to Chinese Resistance,” GOUCOCH L.0 N5522, TTLTQG-II, HCMC, 8 March 1894. ↩

-

Su Lin Lewis, Cities in Motion: Urban Life and Cosmopolitanism in Southeast Asia, 1920–1940 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016), 28. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSEA 307.7609590904 LEW) ↩

-

Anthony Reid, Southeast Asia in the Age of Commerce, 1450–1680 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1988). (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSEA 959 REI) ↩

-

Meeting of the Sài Gòn Chamber of Commerce, Session 321, GOUCOCH L.0 N5522, TTLTQG-II, HCMC, 29 December 1893. ↩