The Prewar And Postwar Art Scene In Singapore Modernist Artists and Art Spaces

Introduction

In September 1935, a group of immigrant Chinese artists established the Society of Chinese Artists (SOCA; 中華美術研究會), or Société des artistes Chinois, in Singapore. These Modernist artists were distinct from the preceding generation of artists, who were mostly born in the 19th century and schooled in the classics under the tutelage of traditional scholars, and whose works were produced in the traditional mode.

In this paper, I examine the prewar and postwar (late 1920s–early 1950s) art scene in Singapore: the life and work of the active but lesser-known SOCA Modernist founders, the relationships among them, the prevalent styles of their work, the historical and social circumstances that shaped their art, and the art spaces they used. Although these artists are neither well documented nor canonised, they were part of the vibrant prewar and postwar art scene. My study reveals a microcosm of artistic germination and rich human dynamics in the prewar and postwar art scene and fills the gaps in our knowledge of early Singapore art history.

The art scene from the turn of the 20th century up to the eve of Singapore’s independence has been analysed by Yeo Mang Thong as consisting of four strands of development:1

The period between the late 19th and early 20th centuries, centring

around individuals of cultural influence, such as Khoo Seok Wan, his

literary circle and the sojourning scholars who offered their literati

skills (calligraphy and painting) to the Chinese mercantile community;

the period corresponding to the Chinese Republican years, which saw

the rise of graphic art (woodcut prints and cartoons) as a new form of

social expression, and a group of Modernist artists in exile from China,

mostly members of SOCA;

Singapore under the Japanese Occupation (1942–45); and

unique artistic personalities, namely Tchang Ju-ch’i, Situ Qiao, both

prominent patriotic artists of the prewar period, and Austrian sculptor

Karl Duldig, who lived and worked in Singapore in 1939–40.

The present study focuses on the second strand of development, drawing on a wide range of materials, including public and private archives, newspapers, school yearbooks, clan association annuals, business directories, magazines, periodicals and literary publications. With secondary research, I pieced these fragments of information together, to create a more comprehensive and historically framed network of human relations, and reconstruct Singapore’s early art history.

The Founders of the Society of Chinese Artists

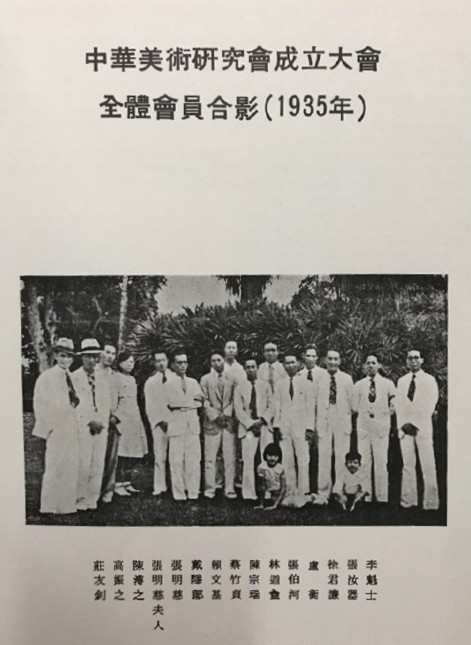

A group photograph (Figure 1) of SOCA’s founding members around September or October 1935, shortly after the society had been registered and their first meeting held, marks the beginning of this investigative journey. According to the photo’s caption, the artists pictured are as follows: (from right to left) Lee Kueh Sei, Tchang Ju-ch’i, Shu Chun Lien, Lu Heng, Zhang Bohe, Lin Dao’an, Chen Chong Swee, Cai Zhuzhen, Nai Wen Chie, Dai Yinlang, Chang Ming Tzu, Mrs Chang Ming Tzu, Chen Pu Chie, Kau Chin Sheng and U-Chow.

SOCA was originally a smaller gathering of alumni from art schools in Shanghai2 called the Syrens Art Association. They must have realised, however, that limiting membership to Shanghai alumni was denying them the critical mass needed for a lively art scene, and that there were many more interested artists out there. Formed in early 1935, Syrens very quickly opened up for wider membership by September and changed its name to Society of Chinese Artists.

Thus the Shanghai alumni formed SOCA’s core. Tchang Ju-ch’i, Cai Zhuzhen, Chen Chong Swee,3 Chen Pu Chie and Lee Kueh Sei were graduates of Shanghai Art Academy, Shu Chun Lien of Xinhua Academy, and Zhang Bohe of Shanghai University. Although it has yet to be established if their periods of schooling coincided, we may infer that their common Shanghai experience fostered a nucleus of shared interest that brought them together while in Singapore. Here, they put their connection to use, forming the art society to organise exhibitions and promote their art.

The society grew year by year, and by 1940 it was 40-strong. Four of its members died during World War II, but SOCA bounced back after the war, with 65 registered members in 1948.

Same Path, Different Destinies

Of the SOCA artists who were active in the prewar as well as preindependence art scene, a handful are well documented and have been canonised as pioneers of a unique Singapore-Malayan style, including Liu Kang, Chen Chong Swee, Chen Wen-hsi, Cheong Soo Pieng, Lim Hak Tai and Georgette Chen. This paper aims at filling in the gaps of our knowledge about the other artists – those who were part of this critical mass setting the Singapore art scene abuzz, but whose careers would take different turns, particularly due to the war.

Many founding members would recede into the background, and some even retreated from the scene. I have written about Tchang Ju-ch’i, Lu Heng and Chen Pu Chie elsewhere,4 and my research did not yield much information on Kau Chin Sheng5 and Nai Wen Chie.6 Although this paper does not offer an exhaustive account of the founding members, it reconstructs a fuller picture of the scene.

Lee Kueh Sei (李魁士; c. 1902–71) was born in Jieyang, Chaozhou, and had close links with the Teochews in Muar, Johor. A graduate of the Shanghai Academy of Art and National Academy of Art (Hangzhou), Lee was a favoured student of painter Liu Haisu (刘海粟). Lee was in Malaya possibly as early as 1928, when he posed for a picture with a young Liu Kang (刘抗) in Muar.7

Between 1932 and 1937, Lee taught at Chung Hwa in Muar, and at Tao Nan School, The Chinese High School and Tuan Mong School in Singapore, as well as the Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts (NAFA), mostly on a part-time basis. By 1938, it seems Lee had left teaching and started Khai Ming Bookstore (開明書店) with his friend Lu Heng. Lee was active within the Teochew community – he was one of the founders of the Kek Yeoh Association in 1938 – and was also frequently mentioned in the Tao Nan alumni association Nanlu Xueyouhui (南廬學友會) and later in 1948 the Jinshi Shuhuashe (金石書畫社), a society dedicated to classical painting, calligraphy, seal carving and ancient inscriptions.

Lee painted in the Shanghai School style inherited from masters such as Ren Bonian and Wu Changshuo and perpetuated by the vibrant mercantilism of Shanghai where Lee had his formal art education. Most of Lee’s extant and published works show a strong preference for dramatic composition, excellent brushwork and flamboyant calligraphy – all characteristics cherished by the Shanghai School (Figure 2). No cartoons or woodcuts – in vogue in the 1930s – have been found in Lee’s oeuvre.

Lee gave a public talk on art in 1938 at the invitation of the Kuo Yu Chinese Institution run by fellow SOCA member Chang Ming Tzu, and also wrote a short review of an exhibition of works by Wang Jiyuan, a professor of the Shanghai Art Academy.8 Both instances reveal Lee’s thoughts on art. Obviously influenced by the education philosophy of Cai Yuanpei, father of modern Chinese education, Lee believed that art had motivational power and could nourish one’s spiritual life; it was a way of expressing one’s ideas and emotions. However, at the height of Japanese aggression in China, Lee thought art should serve the cause of patriotism by explicitly depicting mass suffering to inspire people to rise up against oppression.

Lee was incarcerated by the Japanese army in 1942 shortly after Singapore fell. After his release, Lee largely went by the name of Lee Ta Bai, perhaps to evade persecutors. He remained active in social gatherings and taught from time to time at NAFA, but it was said that his health had been badly affected during his incarceration and he suffered various illnesses during the 1960s. He passed away in September 1971 and was remembered in his obituary as an artist and cultural personality.9

Shu Chun Lien (徐君濂 Xu Junlian; 1911–c. 2000) was a Shanghainese who received his formal art training at Xinhua School of Art. Shu’s name first appeared in Singapore Chinese dailies around August 1933, in an announcement for the second Chinese trade fair held at Great World Amusement Park. He is mentioned together with artists Tchang Ju-ch’i, Lin Dao’an, Zhang Bohe and Huang Cheng Chuan (黃清泉).10 Around the same time, Shu began working for Sin Chew Jit Poh (《星洲日報》) as an editor and artistic director of its literary supplement and pictorial, which Tchang and Lin also worked on.

Shu painted in a relatively academic realist style, as can be seen in the two oil paintings he contributed to the SOCA exhibitions in 1939 (Malay Kampong) and 1940 (Landscape) and published in the catalogues. His other oil works of the prewar period were documented in Chinese newspaper articles, but unfortunately without images.

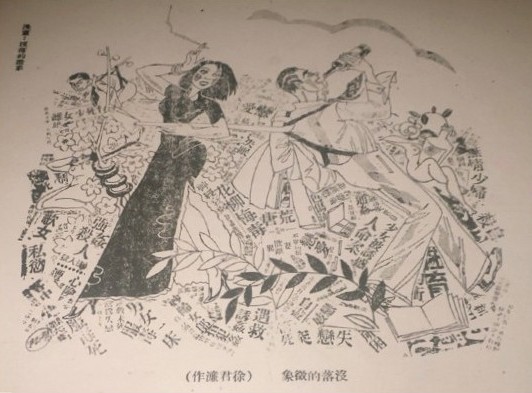

Shu was probably more prolific in producing graphic and design works. He was close to his colleagues at Sin Chew Jit Poh, some of whom started a magazine dedicated to current affairs and contemporary literature called Up to Date (《今代》). Shu wrote fictional pieces and drew satirical cartoons for the magazine. An elaborate cartoon titled Signs of a Decline (没落的徵象) can be found in the inaugural issue of May 1934 (Figure 3). Around the same time, Shu started a short stint teaching art at The Chinese High School.

Shu’s other illustrations appeared in an essay on children’s health in a pictorial published in February 1936 by the Nantao Publishing House (南島出版社) owned by Phua Chay Long (潘醒農), and a map of Hainan island commissioned by the Hainan Association for a war fundraising effort in March 1939. He also produced a drawing for a stage layout when the Nanyang Chinese Students Society (NCSS) created a performance space and stage on their pre mises in 1934.11 In July 1941, Shu teamed up with his Sin Chew colleague Lin Dao’an to set up the Daying (“Big Eagle”) Art Studio (大鹰画室), offering painting, drawing and signage production.12

Ink painting was also part of Shu’s repertoire. In 1974 and 1979, Shu – who had returned to China for good around the early 1950s – presented his ink paintings to Liu Kang and his wife, who were part of an official delegation of Singapore artists on a historic visit to China, which had just reopened its doors to the world. These paintings have been kept in the Liu Kang family archive; one of them was exhibited in the Asian Civilisations Museum in 2019–20.13

Shu was also well known for his literary endeavours. In 1950, his novel and short stories were published as Rooftop Hotel (《天台旅館》) and Winter in Dingjiaqiao (《丁家橋之冬》) by Nanyang Siang Pau (《南洋商报》). He was also active in both Peking opera and modern theatre, performing on radio with the Ping She (平社) opera association and in various productions presented by NCSS.

Zhang Bohe (張伯河; 1901–57) came from Puning, Chaozhou, and studied in Shantou’s Zhendong Secondary School (震东中学), where his artistic talent won him a scholarship to pursue art at the Shanghai Arts College under Shanghai University. In 1926, he graduated with the first batch of the Arts and Crafts class of its teachers’ training programme.

Not much else is known about Zhang’s life, but he left behind enough works for his son to organise an exhibition and publish a catalogue of all his works in 2005 in Singapore.14 This catalogue is a summary of Zhang’s multifaceted talent – as a Chinese ink painter, sketcher, watercolourist, designer, poet and art educator (as demonstrated by his essays on teaching art).

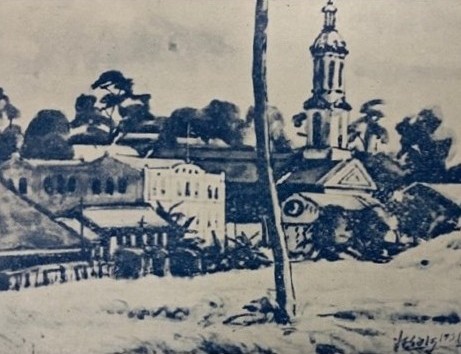

Zhang’s teaching tenure at Tuan Mong School in Singapore gave him a platform to express his artistic ideas. For example, he was the artistic director for the school’s yearbook of 1931. His watercolour painting of the

school building in Tank Road facing a wide field forms the establishing shot of Tuan Mong at the start of the publication (Figure 4). He also made drawings for chapter dividers and page backgrounds, and three pencil sketches.15

Lin Dao’an (林道盫; 1908–42) was the younger brother of Sin Chew Jit Poh’s manager, Lin Aimin (林靄民). A native of Fujian, the younger Lin was a student of Liu Haisu (刘海粟) at the Shanghai Academy of Art. Before becoming a picture editor at Sin Chew by 1934, Lin was based in Hong Kong, producing advertising illustrations for a wide range of clients.

In 1936, he contributed two oil paintings for the inaugural SOCA exhibition, but by 1937 he seemed to have retreated from active participation. However, he continued to produce graphic and advertising works for Sin Chew and its pictorial magazine Starlight, and Up to Date magazine. In the 7th SOCA exhibition, he was named as one of the SOCA martyrs who died during the Sook Ching purge in early 1942, which suggests that he kept close ties with the artists.

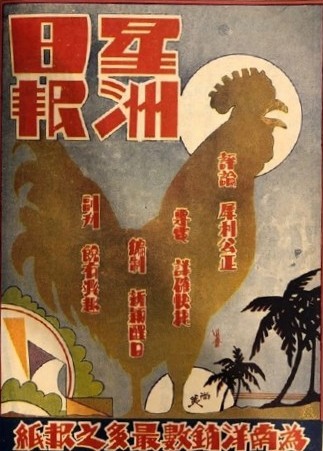

At present, no oil paintings by Lin have been located, but his graphic works have been preserved in many publications and newspapers. In a colourful advertisement created for Sin Chew, Lin’s striking lettering takes centre stage, while a rooster, shoreline and coconut trees are silhouetted in blocks of flat colour (Figure 5). His signature is executed with a hard-nibbed pen instead of a brush, reflecting a general preference among young intellectuals of that era for the convenience of modern fountain pens, pencils or technical writing implements.

In the inaugural issue of Up to Date, Lin contributed three delightful cartoons featuring beautifully drawn figures, titled The Shape of an Elephant, Progress? Or Digress? and Between the Two Sexes. Here his signature also reveals a playful humour as he drags out the complicated radicals and strokes of the word 盫 to form a string-like scribble (Figure 6). In this issue, Lin also wrote a short piece on his mentor, Liu Haisu.16

While in Singapore, Lin maintained ties with artists in Shanghai. In September 1937 he was recruited to join Jiuwang Manhua (《救亡漫画》), established by patriotic graphic artists in response to the outbreak of war between Japan and China. The group included prominent cartoon artists such as Ding Cong (丁聪), Zhang Guangyu (张光宇), Huang Miaozi (黄苗子), Huang Yao (黄尧), Ye Qianyu (叶浅予) and Zhang Leping (张乐平).

Lin’s Shanghainese connection also brought him close to Shu Chun Lien, his fellow picture editor at Sin Chew as well as Up to Date contributor. The two men set up Big Eagle Studio. Advertisements announcing the establishment of the art studio were carried in both Sin Chew and Nanyang Siang Pau, the former touting it as a new wave in the art world. The studio’s vision statement – “The capital of a business is the advertising; art is the life of the merchandise” – was said to have caused a stir in the business and art community in Singapore.17

Lin’s high-profile career and dynamic partnership with Shu were cut short when Lin died during the Sook Ching purge in February 1942, barely seven months after the launch of Big Eagle Studio. He was only 35.18

Cai Zhuzhen (蔡竹貞; c. 1900–74) trained at the Shanghai Academy of Art under Liu Haisu. He rarely exhibited his works in the years leading up to the war in Singapore, though his participation was recorded in the 1936 exhibition and the iconic cartoon and photography exhibition in 1938, which had entries by artists in the Malay Archipelago. A rare image of Cai’s work can be found in the 1948 SOCA exhibition catalogue. It depicts an idyllic scene of three Malays on a hilltop overlooking a vast expanse of sea

and village (Figure 7). In Cai’s obituary, he was lauded as a pioneer in the art world and a photographer in Singapore.19

Dai Yinlang (戴隱郎; 1907–85) was an enigma in the Singapore/Malaya art world. Born in Kuala Lumpur, Dai found himself in Shanghai at a time (1931–35) when left-wing socialism was taking hold in literature and the visual arts. He most likely became an activist and joined the movement spearheaded by Lu Xun to popularise woodcut prints and promote social change.

Dai subsequently returned to Malaya and found work at Nanyang Siang Pau as the editor of the cartoon supplement (《文漫界》). In 1934, Dai was briefly in Hong Kong, where he started a woodcut society, the Deep Cut Woodcut Society (深刻木刻研究會), and published a 7,000-word Social Realist critique of symbolist poetry, which was then fashionable in China.20

Dai likely arrived in Singapore around the mid-1920s armed with a heavy left-wing mandate directly from the Communist movement in China, and he was widely respected for his political endeavours.

He tirelessly promoted the satirical cartoon as a vehicle for social and political criticism and saw great historical importance in this new art form.21 He played the role of mentor and critic to his fellow SOCA artists. For instance, he wrote an extensive review of SOCA’s inaugural exhibition in 1936, giving the artists individual critiques.22 His sharp-lined cartoons with anti-Japanese and anti-Imperialist themes were the flavour of the day in Singapore and Malaya, particularly at the height of Chinese patriotism triggered by Japanese aggression in China from the summer of 1937 onwards.

Almost immediately after the Marco Polo Bridge incident, Dai organised the first Singapore-Malayan Graphic Art Exhibition together with Shu Chun Lien and a number of artists. Featuring some 185 works from 40 artists selected by a highly esteemed panel of artists,23 the spectacular exhibition kicked off in Singapore in 1938 before proceeding on a tour of the peninsula.

Dai is revered today in art-historical writings for his explicit and accessible images of political righteousness, of China’s oppression by imperialism and militarism. Unfortunately the second half of Dai’s life, presumably in China right through the 1980s, has not been well studied.

Chang Ming Tzu (张明慈/张铭慈;24 c. 1898–1982) was the non-artist in SOCA. A Yunnanese by birth and a graduate of Peking University, Chang came with an illustrious political background, having participated in the KMT-led National Revolution (国民革命; 1924–27), which brought him to Shanghai, where he had his first encounter with Southeast Asia, or Nanyang (南洋). He was part of the editorial team of the seminal journal dedicated to Southeast Asia, The Nanyang Monthly (《南洋研究》), published by Jinan University (暨南大学). Fluent in Japanese, Chang translated Japanese research and reports about Southeast Asia for the journal. His translation of Nanyo Sodan (《南洋叢谈》) by Fujiyama Raita25 was published by Jinan in 1931.

In the mid-1930s, Chang set up the Kuo Yu Chinese Institution (中国语文 学院) at 38 Dhoby Ghaut, which was at various times neighbour to Huang Pao-fang’s Mei Tong Art Studio at number 42, and Liu Kang’s Morrow Studio at number 35.

Kuo Yu was part of the larger Chinese cultural scene; it actively organised public lectures by visiting luminaries from China, as well as local speakers. Lee Kueh Sei, for example, gave a talk titled “Art and Life” in 1938. During the Japanese Occupation, the institution was renamed the East Asian Japanese Language Institution (my translation; 东亚日本语学院).

In a seminar organised by Syonan Asahi (昭南日报; The Syonan Daily) to commemorate the first anniversary of the fall of Singapore to Japan, Chang was a speaker alongside Chong Beng Si (钟鸣世) of NAFA and Cupid Art Studio (天使画室), and Goh Seng Yeok (吴盛育) of Mayfair Musical and Dramatic Association (爱华音乐社), and spoke about the 21 Japanese language schools that had sprung up on the island.26

Steeped in classical Chinese literature, Chang often shared his poetic skills to lend literati credence to artists’ gatherings and works of a more traditional style by the artists he socialised with. Chang’s collection of poems, South Sea Poems (《南遊吟草》), offers a glimpse of the vibrant art scene of the period.

He wrote colophons and most probably personally inscribed works by Tsai Wang Ching (蔡寰青), Wong Jai Ling (黄载灵), Xu Qigao (许奇高) and Liu Kang.27 When gifted a painting by Xu Beihong (徐悲鸿), Chang composed a poem to remember the occasion.28 To commemorate the visits to Singapore by Luo Ming (罗铭) and Liu Haisu, both well-known Chinese artists, Chang wrote long poems that could well double-up as surveys of their exhibitions, because the titles and descriptions of the paintings were cleverly woven into the text.29 These literary details may be useful in future identification of these artworks, should they be rediscovered.

Chang was a learned Buddhist scholar much admired in the Buddhist community, and his poems are interesting records of visiting monks and various Buddhist activities in Singapore.30

Over the years, Chang and his Kuo Yu Chinese Institution most probably lent organisational support as well as political connections to the numerous artistic and cultural activities taking place during this nascent period of Singapore art. But the specifics of his involvement in the art scene remain unclear. Further research would help to illuminate the role that intellectuals like him played in artistic circles in prewar Singapore.

U-Chow (莊有釗; 1907–42) was the brother-in-law of Tchang Ju-ch’i, and was generally known without his family name, Chuang/Zhuang or Chng (莊). Sometime around 1932, he and Tchang became partners of a design and commercial art company, United Painters Studio, operating out of a shophouse at 82 Tank Road, which was also Tchang’s residence.

U-Chow presumably had a good command of English as he was designated SOCA’s English secretary and press manager. It was very likely because of U-Chow that SOCA’s exhibitions and general meetings were covered in the prewar English dailies, such as the Malaya Tribune and The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser.

The most extensive description of U-Chow comes from a delayed obituary written by Chuang U-Ming (莊右銘), which was featured in a special spread in Nanyang Siang Pau dedicated to SOCA’s first postwar exhibition.31 U-Chow was described as self-taught in painting and languages – apparently he taught himself German without setting foot in Europe.

U-Chow and Chuang were both born in Quanzhou and attended the same class, where Chuang noticed U-Chow’s talent in drawing. This talent would later be nurtured by an art teacher when U-Chow became a student at

Raffles Institution in Singapore. A late bloomer, U-Chow graduated from Raffles Institution at 23 and persisted in pursuing a career in art.

In 1931, together with Kau Chin Seng and Lin Chunyuan (林春元), U-Chow won the contract for the construction and graphic design of Great World Amusement Park. In 1933, U-Chow met Tchang; they became close friends, business partners and then family when they married each other’s sister.

Chuang refuted the general opinion that U-Chow’s main source of artistic influence had been Tchang, with an insight that could only have come from being a close acquaintance. In fact, U-Chow preferred the purity and originality found in African and Balinese art.

According to Chuang, U-Chow was also of the opinion that both Xu Beihong and Liu Haisu, two titans of the Chinese Modernist movement then, were unable to paint freely, because they were constrained by their perceptions of their teachers’ styles. U-Chow’s criticism of Xu’s work was specific and pointed – because Xu neglected the importance of sketching and perspective, his figurative works and portraits were poorly executed composites of fragments, resulting in awkward proportions and lifeless subjects.

The Nanyang Siang Pau story featured two of U-Chow’s works, while the SOCA exhibition catalogues of 1939 and 1940 carried some of his watercolours and sketches (Figure 8). One extant work can be found in the collection of one of Chuang U-Ming’s descendants and was exhibited and published by the Asian Civilisations Museum in 2019 in Living with Ink: The Collection of Dr Tan Tsze Chor.32

Prewar and Postwar Art Spaces in Singapore

SOCA grew to a 40-strong society by the time war broke out in Singapore. Their venue had moved from Tchang Ju-ch’i and U-Chow’s United Painters Studio on Tank Road to a space shared with the newly established NAFA at 167 Geylang Road. Like the Tank Road studio, the new venue was also a shophouse, built for mixed residential and commercial use. However, as the society became increasingly active in organising fundraisers for the Sino- Japanese War (1937–45) and hosting visiting luminaries such as Xu Beihong, it had to move its public activities elsewhere.

With its exhibitions growing in size and importance, large venues like the Chinese Chamber of Commerce and Victoria Memorial Hall had become SOCA’s choice for anchor venues by 1939. While SOCA received much support from the Chinese Chamber of Commerce and cultivated a symbiotic relationship with NAFA, whose principal Lim Hak Tai (林學大) was an important member of the society, it also actively maintained a network of alternative venue partners. These partners were the various cultural and civil societies that had sprung up since the new era of progressive China (following the May Fourth Movement), and most probably shared the same pool of audiences and subscribers. This section looks at the lesser-known of these premises, which either ceased to command significance after the war or were replaced by newer or more established venues.

Nanyang Chinese Students Society (南洋青年励志社). The NCSS was one of the most active clubs dedicated to the well-being of the vast number of young Chinese people in Nanyang. It was akin to a school alumni club, except that it was open to all young working adults, particularly targeting the burgeoning ranks of white-collared professionals. It organised sports tournaments, lectures on issues pertaining to China’s situation and plight, charity fundraisers for a myriad of causes in China, exhibitions and baby shows.33 In 1929, the society organised one of its earliest Singapore-based art exhibitions, curated by a team of artists and designers that included Tchang Ju-ch’i. The exhibition was reported to have made a commendable pioneering effort in promoting local artistic expression.

After its formation in 1920, the NCSS moved at least five times, as its events grew larger and increasingly popular, before it finally settled in a YMCA property on Prince Edward Road, which came with its own sports field, in 1935.

When Xu Beihong visited in February 1939, SOCA held a welcome tea there. The premises were used regularly as a rehearsal venue for Mandarin plays, choir practice and lectures. In 1935, members of the NCSS and a group of photography enthusiasts staged an exhibition of more than 300 works from Malaya, Singapore and Hong Kong. The exhibition opening was a garden party staged in the NCSS’s leafy compound.34

These gatherings suggest that exhibition openings were officious in nature, often graced by high-ranking representatives of the government, members of the Chinese Consulate, and British officials. Speeches were reported almost verbatim, and the art works in the exhibitions were written up and published in the following days in the Chinese dailies. These occasions also show the social importance of SOCA, which was progressive and open, with its artists intimately connected with the business world and the community at large.

Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA), Raffles Quay. Opened in 1923 as YWCA’s headquarters, the Blue Triangle Lunch and Rest Room (as it was first named) served as a central location for working women to network. Designed by Swan & Maclaren, the two-storey bungalow stood on the reclaimed land of Raffles Quay (also referred to as Finlayson Green, located at the end of the line of the Telok Ayer Market trolley bus route) (Figure 9). The “rest room” on the upper floor was “large and airy, very comfortably furnished, and has a delightful view over the harbour”.35

This was the venue of SOCA’s first exhibition in 1936, as well as the 1937 and 1938 exhibitions.36 It is highly likely that this was a premium exhibition space in town, as it was the choice of venue for locally and regionally based European artists, as well as those who were passing through – the Art Club (Singapore) members, Jean Le Mayeur, Tania Zarutsky, Willem van der Does from Batavia, Gerard P. Adolfs, Julius Wentscher and wife. Jean Le Mayeur, the Belgian artist of Balinese fame, for instance, held four exhibitions here between 1935 and 1941.37 SOCA member Looi Koh Seng exhibited his works with the colonial wives of the Art Club in June 1939,38 including Mrs K. M. Chasen, who was married to the director of the Raffles Museum, Frederick Nutter Chasen.

Nanyang Siang Pau’s report on the 1938 exhibition carried a photo of the exhibition opening, in which men in white suits fill a well-appointed room, the walls lined with paintings. A total of 165 paintings were presented, indicating the generous size of the “rest-room”.39

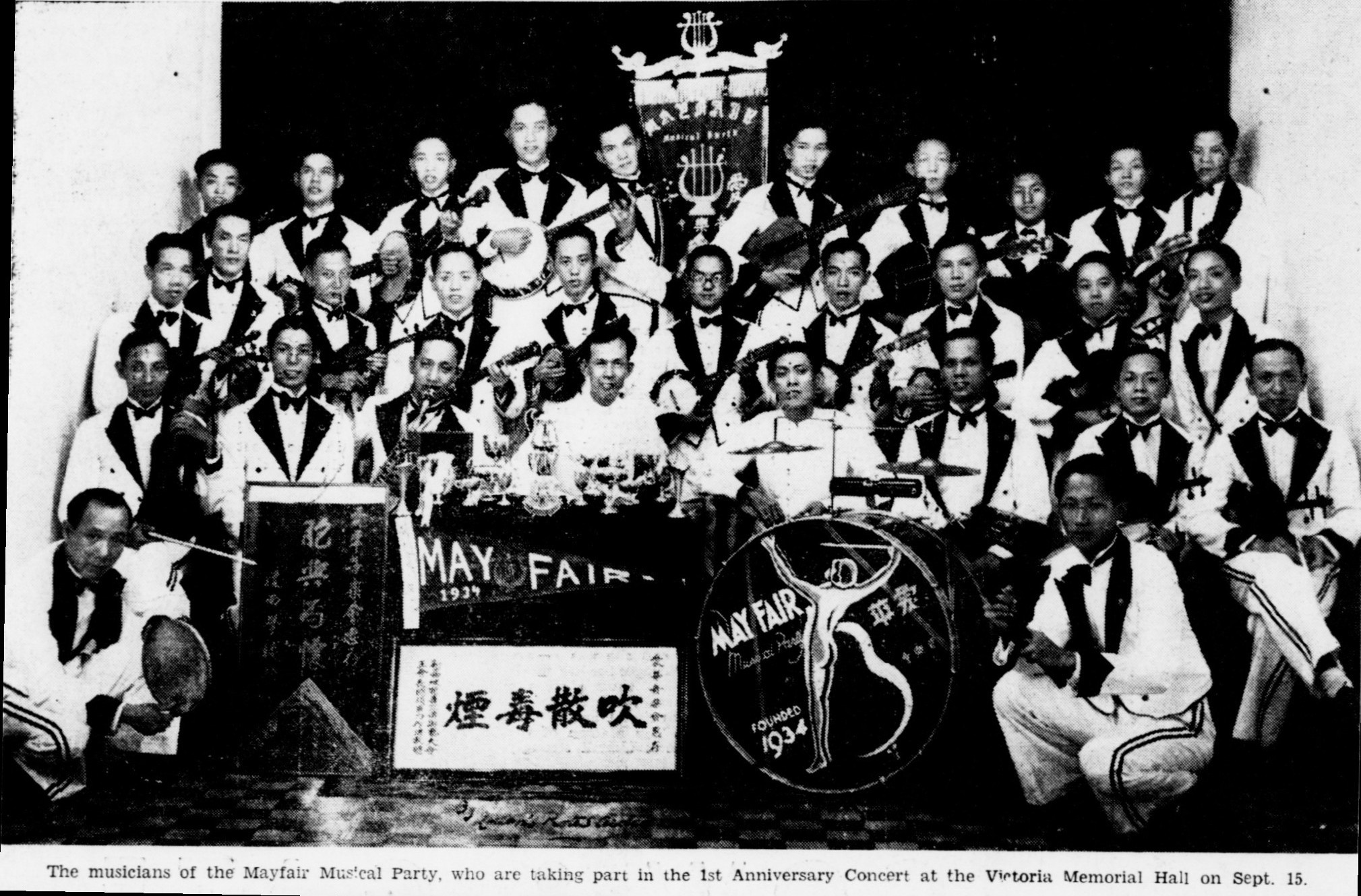

Mayfair Musical and Dramatic Association (愛華音樂社). This society started as a band in June 1934 under the name Mayfair Musical Party (Figure 10). Its founder, Goh Seng Yeok, was a Singapore-born Chinese. The Mayfair band played regularly at openings, fundraising shows and social events in the Chinese community.

An Ai Tong Primary alumnus, Goh brought Mayfair to play at the school’s concerts. The band provided the musical interlude, for example, at a 1935 Mandarin speech competition organised by the NCSS and hosted at Ai Tong. When the alumnus presented modern plays and concerts, Mayfair provided performance and accompaniment and Goh even played a female role in a new play, Huanengying (花弄影; Flowery Shadows).40 Mayfair would later organise the first mass weddings in Singapore, before World War II.

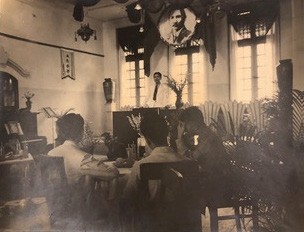

Without a sufficiently large venue in its early years, Mayfair rehearsed in the homes of friends and patrons. By 1938, however, under the patronage of various luminaries, including cinema mogul Run Run Shaw (邵逸夫), Mayfair established its headquarters in two units at the Shaw Brothers’ building on Robinson Road (Figure 11). The premises came with a large hall on the second level. Here, SOCA hosted a send-off-cum-welcome party on 2 November 1939 for Xu Beihong, who was leaving for India, and Yu Shihai (喻世海), a prominent cartoonist who had recently arrived from China.41 A rare photograph of the interior, from the Liu Kang family archives and dated 3 March 1949, captures three men sitting around a table, while Liu, in a white suit, stands on a raised podium under a portrait of Sun Yat-sen, possibly rehearsing a speech (Figure 12).42

Later that year, after the Chinese Communist Party won the civil war in China and as the Kuomintang staked out Taiwan to continue the Republican government, Mayfair openly celebrated the new Chinese National Day on 1 October with a display of the new flag on its building façade and the singing of the new anthem, “March of the Volunteers”.

The British Military Administration was shocked by Mayfair’s enthusiasm for the Communist regime and promptly started an investigation. In December 1950, they forced Mayfair to disband and arrested Goh Seng Yeok, who later exiled himself to China.43 Goh died in Beijing on 4 April 1962 at the age of 53.

Mayfair’s short lifespan of 16 years underlines the ideological confusion and divided loyalties created by China’s years of war with Japan and the rise of Communist China. Like many war-battered Chinese in Singapore, Goh was convinced that he intended to fly the “flag of the New China… in honour of the new Chinese government”, not as a Communist.44

Conclusion

The art scene of the Chinese community in prewar and postwar Singapore was dominated by young mid-career artists, who were educated and well trained in the arts. Some were exceptionally versatile. Many had had their artistic initiation in China, steeped in the tradition of calligraphy and ink painting. Their art flourished despite war and natural calamities in China, as well as the post-1929 economic crisis, as art became a powerful way to stir up sympathy and support for humanitarian causes. In the absence of proper art spaces for exhibition and interaction, the artists sought out all options available – in schools, clubs, charitable institutions – to connect to the different sectors of society.

This paper has documented the rudiments of the prewar and postwar artistic community within the Chinese milieu, and placed the many forgotten individuals in an expanded art history of Singapore, against the larger backdrop of World War II and historical events in China. Their art-making formed a foundation for art to develop in postwar and preindependent Singapore so that by the 1970s and 1980s, Singapore could identify that generation we call the pioneer artists.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Asian Civilisations Museum. Living With Ink: The Collection of Dr Tan Tsze Chor. Singapore: Asian Civilisations Museum, 2019. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 759.951 LIV)

Chang, Ming Tzu. 南遊吟草 [South sea poems]. Singapore: Chang Ming Tzu, 1931.

Leonard K. K. Chan 陳國球. Xianggang de shuqing shi 香港的抒情史 [Hong Kong in its history of lyricism]. 香港: 中文大學出版社, 2016. 164–65. (From National Library Singapore, call no. Chinese C810.04 CGQ)

Duan meng xuexiao ershiwu zhounian jìnian kan 端蒙学校二十五周年纪念刊 [Tuan Mong School’s 25th anniversary commemoration publication]. Singapore: Tuan Mong School, 1931.

今代 [Up to date], vol. 2, 16 May 1934.

Lee, Chor Lin. “Chinese Graphic Artists in Pre-war Singapore.” BiblioAsia 17, no. 2 (2021).

Malaya Tribune. “Red Flag Flies in Singapore.” 7 October 1948, 1. (From NewspaperSG)

Nan Kwong Weekly 南光周刊. “Shengzhan wansui zuotan hui” 圣战完遂座谈会 [Completing the Holy War: A forum]. 15 February 1943, 28–29.

Nanyang Siang Pau 南洋商报. “Da shijie di er jie guohuo zhanlan hui tekan jinri chuban” 大世界第二屆國貨展覽會特刊今日出版 [Catalogue of the Second National Products Exposition at the Great World goes on sale today]. 5 August 1933, 8. (From NewspaperSG)

—. “Qing nian lizhi she xinzao xitai yi jungong shang ni tianzhì bujing” 靑年勵志社新造戲台已竣工尚擬添置布景 [The stage of the Nanyang Chinese Students Society is completed with backdrop]. 3 February 1934, 5. (From NewspaperSG)

—. “Ai tong xiaoyou hui xiju zu jin wan zhuyan donghua chou kuan youyihui” 愛同校友會戲劇組今晚助演東華籌欵遊藝會 [Drama group of Ai Tong School Old Boys’ Society performs at the fundraiser for Tong Hwa Chinese School tonight]. 17 June 1935, 7. (From NewspaperSG)

—. “Guoyu ye xueyuan yanjiang hui likuishi jun jiangyan ‘yishu yu rensheng’” 国语夜学院演讲会李魁士君讲演『艺术与人生 [National Language Night School hosts talk by Lee Kueh Sei on “Art and Life”]. 9 January 1936, 8. (From NewspaperSG)

—. “Manhua de shidai jiazhi: Dai yin lang zai guoyu ye xueyuan zhi yan ci” 漫畫的時代價值: 戴隱郎在國語夜學院之演詞 [The value of cartoons in our time]. 17 February 1936, 5. (From NewspaperSG)

—. “Shangshu meishu pin chenlie lou shang, kaimu li zai lou xia litang juxíng. Xing zhou huaren meishu yanjiu hui mei zhanhui” 上述美術品陳列樓上,開幕禮在樓下禮堂舉行. 星洲華人美術研究會美展會 [Singapore Society of Chinese artists exhibition]. 26 June 1936, 6. (From NewspaperSG)

—. “Línggan quan wai” 戴隱郎靈感圈外 [Dai Yinlang: Beyond inspirations]. 28 June 1936, 11. (From NewspaperSG)

—. “Wangjiyuan de hua” 王济远的画 [Wang Jiyuan’s paintings]. 15 April 1938, 29. (From NewspaperSG)

—. “Huaren meishu yanjiu hui mingri huansong xubeihong” 華人美術研究會明日歡送徐悲鴻 [SOCA bids farewell to Ju Peon tomorrow]. 1 November 1939, 6. (From NewspaperSG)

—. “Líndao an xujunlian deng chuangli daying huashì” 林道盦徐君濂等創立大鷹畫室 [Lin Dao’an, Shu Chun Lien and others set up Daying Art Studio]. 4 July 1941, 9. (From NewspaperSG)

—. Zhuang, Youming 莊右銘. “Guanyu zhuang you zhao (zai yu huaren meishu yanjiu hui di liu jie meizhan tekan)” 關於莊有釗 (載于華人美術研究會第六屆美展特刊) [Catalogue of the sixth SOCA annual exhibition]. 24 December 1946, 1. (From NewspaperSG)

—. “Fu zhengsi zai xian bao ban ling xia aihua she bei jiesan” 輔政司在憲報頒令下愛華社被解散 [Government orders dissolution of Mayfair Musical and Dramatic Association]. 30 December 1950, 5. (From NewspaperSG)

—. “Likuishishi shi” 李魁士逝世 [Lee Kueh Sei passes away]. 9 September 1971, 16. (From NewspaperSG)

Pan Xingnong 潘醒农. Chao qiao suyuan ji 潮侨溯源集 [Essays on the roots of overseas Teochews]. 北京: 金城出版社, 2014. (From National Library Singapore, call no. Chinese RSING 959.5004951 PXN)

Shuai Minfeng 帥民風. Malaixiya huaren meishu shi yanjiu 馬來西亞華人美術史研究 [A history of the art by the Chinese in Malaysia]. 北京: 中國社會科學出版社, 2013. (From National Library Singapore, call no. Chinese RSEA 709.595 SMF)

Tengshan Leitai 藤山雷太. Nanyang cong tan 南洋叢谈 [Studies on Nanyang]. 张铭慈译. 上海: 国立暨南大学, 1931. (From National Library Singapore, call no. Chinese RDTYS 959 TSL)

Straits Times. “Lunch Room on Finlayson Green.” 8 November 1923, 10. (From NewspaperSG)

—. “The Scene on the Lawn at the Opening of the Overseas Chinese Photographic Exhibition at the Nanyang Chinese Students Society Premises.” 26 March 1935, 13. (From NewspaperSG)

—. “The Art Club.” 2 June 1939, 12. (From NewspaperSG)

Sin Chew Jit Poh 星洲日報. “Yishu jie yijuntuqi lindao an xujunlian deng chuangli [daying huashi] 藝術界異軍突起 林道盦徐君濂等 創立[大鷹畫室][New groups rising in the arts: Lin Dao’an, Shu Chun Lien and others set up Daying Art Studio]. 4 July 1941, 9. (From NewspaperSG)

—. “Woguo meishujia caizhuzhen shishi” 我国美術家蔡竹貞逝世 [Local artist Cai Zhuzhen passes away]. 17 September 1974, 8. (From NewspaperSG)

Yeo, Mang Thong. Migration, Transmission, Localisation: Visual Art in Singapore (1886– 1945). Singapore: National Gallery Singapore, 2019. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 709.5957 YAO)

Zhang Bohe 张伯河. Zhangbohe huihua shi wen jinian ji 张伯河绘画诗文纪念集 [A Commemorative Collection of Zhang Bohe’s Paintings, Poems and Essays]. Singapore: Zhang Zhongzhao, 2007. (From National Library Singapore, call no. Chinese R 759.95957 ZBH)

NOTES

-

Yeo Mang Thong, Migration, Transmission, Localisation: Visual Art in Singapore (1886–1945) (Singapore: National Gallery Singapore, 2019). (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 709.5957 YAO) ↩

-

Namely, the Shanghai Art Academy, Xinhua Academy and Shanghai Arts College. ↩

-

Chen Chong Swee (陳宗瑞; 1910–85) is the only canonised Singapore pioneer artist who was a founding member of both SOCA and possibly its former incarnation as the Syrens Art Association. Chen’s life and art are well documented, and his writings have been published posthumously by national institutions. ↩

-

For more on Tchang Ju-ch’i (張汝器; 1904–42), Lu Heng (盧衡; 1902–61) and Chen Pu Chie (陳溥之/ 陳普之; 1911–50), see Lee Chor Lin, “Chinese Graphic Artists in Pre-war Singapore,” BiblioAsia 17, no. 2 (2021). ↩

-

Apart from being a founding member of SOCA, Kau Chin Sheng (高振聲) was a business partner with U-Chow in the production of commercial advertising and signage. ↩

-

Although Nai Wen Chie (賴文基) was active through to the 1980s, very little has been documented about him in publicly accessible archives and sources. In the early years of SOCA, his works were mainly sketches, watercolours and oils. ↩

-

Liu Kang family archives. ↩

-

Guoyu ye xueyuan yanjiang hui likuishi jun jiangyan ‘yishu yu rensheng’” 国语夜学院演讲会李魁士君讲演『艺术与人生 [National Language Night School hosts talk by Lee Kueh Sei on “Art and Life”], Nanyang Siang Pau 南洋商报, 9 January 1936, 8; “ Wangjiyuan de hua” 王济远的画 [Wang Jiyuan’s paintings], Nanyang Siang Pau 南洋商报, 15 April 1938, 29. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Likuishishi shi,” 李魁士逝世 [Lee Kueh Sei passes away], Nanyang Siang Pau 南洋商报, 9 September 1971, 16. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Da shijie di er jie guohuo zhanlan hui tekan jinri chuban” 大世界第二屆國貨展覽會特刊今日出版 [Catalogue of the Second National Products Exposition at the Great World goes on sale today], Nanyang Siang Pau 南洋商报, 5 August 1933, 8. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Qing nian lizhi she xinzao xitai yi jungong shang ni tianzhì bujing” 靑年勵志社新造戲台已竣工尚擬添置布景 [The stage of The Nanyang Chinese Students Society is completed with backdrop], Nanyang Siang Pau 南洋商报, 3 February 1934, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Líndao an xujunlian deng chuangli daying huashì” 林道盦徐君濂等創立大鷹畫室 [Lin Dao’an, Shu Chun Lien and others set up Daying Art Studio], Nanyang Siang Pau 南洋商报, 4 July 1941, 9. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

See Asian Civilisations Museum, Living With Ink: The Collection of Dr Tan Tsze Chor (Singapore: Asian Civilisations Museum, 2019), 110–11, figs. 59–60. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 759.951 LIV) ↩

-

Zhang Bohe 张伯河, Zhangbohe huihua shi wen jinian ji 张伯河绘画诗文纪念集 [A Commemorative Collection of Zhang Bohe’s Paintings, Poems and Essays] (Singapore: Zhang Zhongzhao, 2007). (From National Library Singapore, call no. Chinese RSING 759.95957 ZBH) ↩

-

Duan meng xuexiao ershiwu zhounian jìnian kan 端蒙学校二十五周年纪念刊 [Tuan Mong School’s 25th anniversary commemoration publication] (Singapore: Tuan Mong School, 1931) ↩

-

今代 [Up to date], vol. 2, 16 May 1934. ↩

-

“Yishu jie yijuntuqi lindao an xujunlian deng chuangli [daying huashi]” 藝術界異軍突起 林道盦徐君濂等 創立[大鷹畫室] [New groups rising in the arts: Lin Dao’an, Shu Chun Lien and others set up Daying Art Studio], Sin Chew Jit Poh 星洲日報, 4 July 1941, 9 (From NewspaperSG); “Líndao an xujunlian deng chuangli daying huashì.” ↩

-

As Lin’s role in the art scene was largely editorial, it would take another research trajectory to place him in the context of Modernist Chinese graphic art in Southeast Asia. ↩

-

“Woguo meishujia caizhuzhen shishi” 我国美術家蔡竹貞逝世 [Local artist Cai Zhuzhen passes away], Sin Chew Jit Poh 星洲日報, 17 September 1974, 8. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Leonard K. K. Chan 陳國球, Xianggang de shuqing shi 香港的抒情史 [Hong Kong in its history of lyricism] (香港: 中文大學出版社, 2016), 164–65. (From National Library Singapore, call no. Chinese C810.04 CGQ) ↩

-

“Manhua de shidai jiazhi: Dai yin lang zai guoyu ye xueyuan zhi yan ci” 漫畫的時代價值: 戴隱郎在國語夜學院之演詞 [The value of cartoons in our time], Nanyang Siang Pau 南洋商报, 17 February 1936, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Línggan quan wai” 戴隱郎靈感圈外 [Dai Yinlang: Beyond inspirations], Nanyang Siang Pau 南洋商报, 28 June 1936, 11. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

See Shuai Minfeng 帥民風, Malaixiya huaren meishu shi yanjiu 馬來西亞華人美術史研究 [A history of the art by the Chinese in Malaysia] (北京: 中國社會科學出版社, 2013), 107. (From National Library Singapore, call no. Chinese RSEA 709.595 SMF) ↩

-

张铭慈 seems to have been the name he used before his arrival in Singapore. It appears in his works published in Shanghai between 1928 and 1931. See his autobiographical introduction in Tengshan Leitai 藤山雷太, Nanyang cong tan 南洋叢谈 [Studies on Nanyang], trans. Zhang Mingci 张铭慈译 (上海: 国立暨南大学, 1931). (From National Library Singapore, call no. Chinese RDTYS 959 TSL) ↩

-

Fujiyama Raita (1863–1938) was a businessman of the Meiji and Showa eras. From 1917 to 1925, he served as the Director of the Tokyo Chamber of Commerce. In 1927, he established the Fujiyama Industrial Library, with a collection of more than 100,000 books. ↩

-

Shengzhan wansui zuotan hui” 圣战完遂座谈会 [Completing the Holy War: A forum], Nan Kwong Weekly 南光周刊, 15 February 1943, 28–29. ↩

-

Chang Ming Tzu, 南遊吟草 [South sea poems] (Singapore: Chang Ming Tzu, 1931), 9, 丹绒巴葛蔡寰青山人索句; 10, 题二山居士画梅; 26, 谢左腕画家许奇高绘赠名驹; 40, 提刘抗画家绘赠松——叶. ↩

-

Chang, 南遊吟草, 29, 谢徐悲鸿教授赠画. ↩

-

Chang, 南遊吟草, 34, 赠罗铭画家柬骆清泉兄, 夜览海粟南洋画册. ↩

-

Chang, 南遊吟草, 9, 丹绒巴葛蔡寰青山人索句; 10, 题二山居士画梅; 26, 谢左腕画家许奇高绘赠名驹; 40, 提刘抗画家绘赠松——叶. ↩

-

Zhuang Youming 莊右銘, “Guanyu zhuang you zhao (zai yu huaren meishu yanjiu hui di liu jie meizhan tekan)” 關於莊有釗 (載于華人美術研究會第六屆美展特刊) [About Zhuang Youzhao (contained in the special issue of the 6th Art Exhibition of the Chinese Art Research Association)], Nanyang Siang Pau 南洋商报, 24 December 1946, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Asian Civilisations Museum, Living With Ink, 99, plate 50. ↩

-

See chapter on the Nanyang Chinese Students Society in Pan Xingnong 潘醒农, Chao qiao suyuan ji 潮侨溯源集 [Essays on the roots of overseas Teochews] (北京: 金城出版社, 2014), 82–98. (From National Library Singapore, call no. Chinese RSING 959.5004951 PXN) ↩

-

“The Scene on the Lawn at the Opening of the Overseas Chinese Photographic Exhibition at the Nanyang Chinese Students Society Premises,” Straits Times, 26 March 1935, 13. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Lunch Room on Finlayson Green,” Straits Times, 8 November 1923, 10. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Shangshu meishu pin chenlie lou shang, kaimu li zai lou xia litang juxíng. Xing zhou huaren meishu yanjiu hui mei zhanhui” 上述美術品陳列樓上,開幕禮在樓下禮堂舉行. 星洲華人美術研究會美展會 [Singapore Society of Chinese artists exhibition], Nanyang Siang Pau 南洋商报, 26 June 1936, 6. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Le Mayeur’s exhibitions, held in March 1935, 1936, 1937 and May 1941, were usually between a week and 10 days long. See Malaya Tribune, Singapore Free Press & Mercantile Advertiser and Straits Times of these periods. ↩

-

“The Art Club,” Straits Times, 2 June 1939, 12. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Shangshu meishu pin chenlie lou shang, kaimu li zai lou xia litang juxíng. Xing zhou huaren meishu yanjiu hui mei zhanhui.” ↩

-

“Ai tong xiaoyou hui xiju zu jin wan zhuyan donghua chou kuan youyihui” 愛同校友會戲劇組今晚助演東華籌欵遊藝會 [Drama group of Ai Tong School Old Boys’ Society performs at the fundraiser for Tong Hwa Chinese School tonight], Nanyang Siang Pau 南洋商报, 17 June 1935, 7. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Huaren meishu yanjiu hui mingri huansong xubeihong” 華人美術研究會明日歡送徐悲鴻 [SOCA bids farewell to Ju Peon tomorrow], Nanyang Siang Pau 南洋商报, 1 November 1939, 6. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Liu Kang family archives. ↩

-

“Fu zhengsi zai xian bao ban ling xia aihua she bei jiesan” 輔政司在憲報頒令下愛華社被解散 [Government orders dissolution of Mayfair Musical and Dramatic Association], Nanyang Siang Pau 南洋商报, 30 December 1950, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Red Flag Flies in Singapore,” Malaya Tribune, 7 October 1949, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩