Reel Life Singapore: The Films of Clyde E. Elliott

Clyde Elliott was the first Hollywood director to shoot a feature film in Singapore. Chua Ai Lin examines the authenticity of the three movies he produced here in the 1930s.

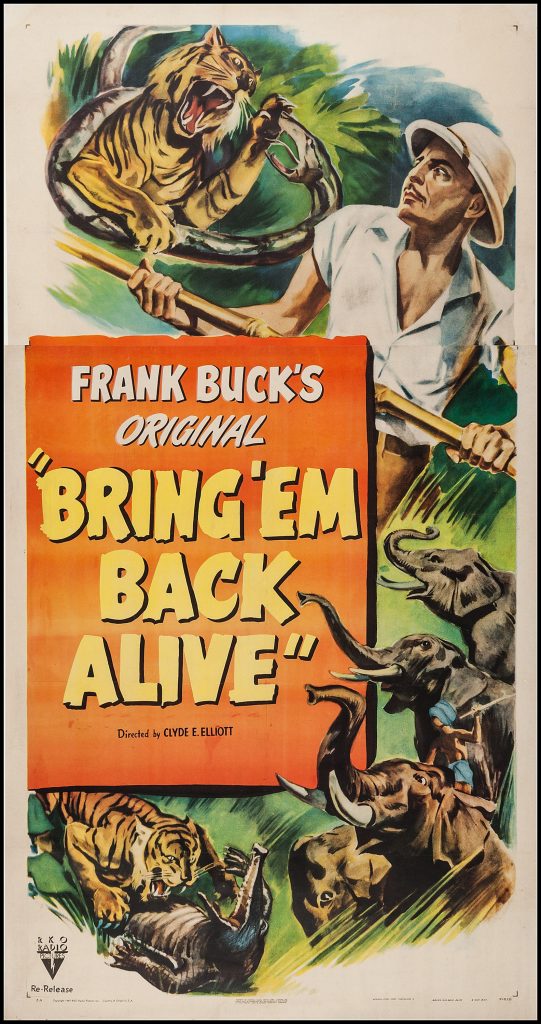

Bring ‘Em Back Alive (1932) was a documentary feature based on the adventures of Frank Buck, a Texan wildlife collector who established his base in Singapore during World War I. Directed by Clyde E. Elliott, the film’s box office takings hit a million dollars within eight months of its release. Image source: Iceposter.com.

Bring ‘Em Back Alive (1932) was a documentary feature based on the adventures of Frank Buck, a Texan wildlife collector who established his base in Singapore during World War I. Directed by Clyde E. Elliott, the film’s box office takings hit a million dollars within eight months of its release. Image source: Iceposter.com.Singapore entered Hollywood’s popular imagination at the turn of the 20th century when motion pictures began showing scenes of a modern and exotic Asian port city with a heady mix of the East and the West.

In January 1936, an article in The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser suggested that with so many American filmmakers arriving on its shores, Singapore was fast “becoming the equatorial Hollywood”.1 Just two months later, an editorial in the same newspaper entitled “The Film Invasion” described the large influx “of film people from Hollywood”, including “such famous names as Frank Buck, Ward Wing, Tay Garnett, James A. Fitzpatrick, and Percy Marmont, to say nothing of Charlie Chaplin”.2

The earliest footages of Singapore would have been newsreels, documentaries and travelogues. Twenty-four such films from 1900 to 1919 and nine from 1920 to 1928 have been identified, most notably works by the leading international newsreel production company, Pathé, as well as four short films by Gaston Méliès (brother of the famous French filmmaker George Méliès) in 1913, which were screened in American cinemas that year.3

From 1928 onwards, longer feature films of Singapore were produced. Some of these depicted Singapore as an obscure locale in the exotic East with no actual footage of the island, while others tried to inject varying degrees of realism with artificial studio settings and stock footage of scenes of Malayan life.

These films included Across to Singapore (1928), Sal of Singapore (1928), The Crimson City (1928; also known by its Italian title, La schiava di Singapore), The Letter (1928), The Road to Singapore (1931), Rich and Strange (1931), Out of Singapore (1932), Malay Nights (1932; also titled as Shadows of Singapore), Singapore Sue (1932) and West of Singapore (1933).4 Interestingly, none of these films were ever shot in Singapore.

Bring ‘Em Back Alive (1932)

Possibly the first Hollywood director to shoot a feature film on-location in Singapore was Clyde Ernest Elliott, who visited the island on several occasions. Elliott’s first release was a short travelogue as part of the Post Travel Series in 1918, which inspired him to go on to make three feature films in the 1930s: Bring ‘Em Back Alive (1932), Devil Tiger (1934) and Booloo (1938), each time attempting to depict Malaya as realistically as he could within the limitations of the Hollywood studio system.

Building on the established practice of newsreel filming, Bring ‘Em Back Alive was a documentary feature film based on the adventures of Frank Buck, a real-life Texan wildlife collector who had established his base in Singapore since World War I. Already a well-known major supplier of animals to zoos in America, Buck’s book of the same title became a bestseller in the US when it was published in 1930.5

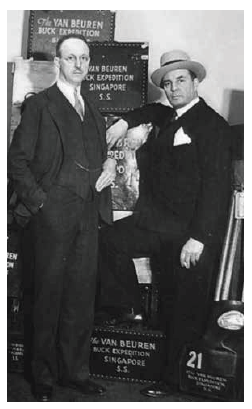

Director Clyde E. Elliott and the wildlife collector Frank Buck getting ready to leave for Singapore to film Bring ‘Em Back Alive in 1932. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Director Clyde E. Elliott and the wildlife collector Frank Buck getting ready to leave for Singapore to film Bring ‘Em Back Alive in 1932. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.This paved the way for the equally successful film adaption of the book by Buck and Elliott, backed by Van Beuren Studios and distributed by RKO Pictures. Box office takings hit a whopping US$1 million within the first eight months of Bring ‘Em Back Alive‘s release and the film became one of RKO’s most profitable productions in 1932.6 Following the release of the film, Buck travelled to London and the US, giving promotional talks and press interviews to coincide with its screening.7

Ostensibly a documentary, Bring ‘Em Back Alive was heavily criticised by more discerning audiences, with American naturalist Harry McGuire referring caustically to Buck’s film as a “hocus pocus” work of “nature faking of the worst kind”. The Straits Times published an article by B. Lumsden Milne, who wrote that he became “hot under the collar” at the string of inaccuracies in the film, and admonished Buck for his inability “to pronounce Malay names correctly”.8

Frank Buck bore the brunt of the bad press as the author of the book but blamed the failings of the film on Clyde Elliott. The latter had readily admitted in public that the scenes of a tiger being shot dead and a python fighting a crocodile had been staged for the camera.9 In response Buck said of Elliott:

“To my mind he has been very silly and rather ridiculous. All pictures are made to entertain people and if a fellow stands up and deliberately spoils the illusion he is biting the hand that feeds him…. I don’t mean we want to fool people – as a matter of fact the picture was made under more natural circumstances than any other of its kind.”10

Such controversies were nothing new in the context of the times. Huber S. Banner, an expert on Java, had this to say about the film:

“The trouble is, though, that after seeing one of these jungle films that are all the rage nowadays – Frank Buck’s epic of the Malayan forests, ‘Bring ‘Em Back Alive’, for instance – nobody will believe that one doesn’t go about in constant peril.”11

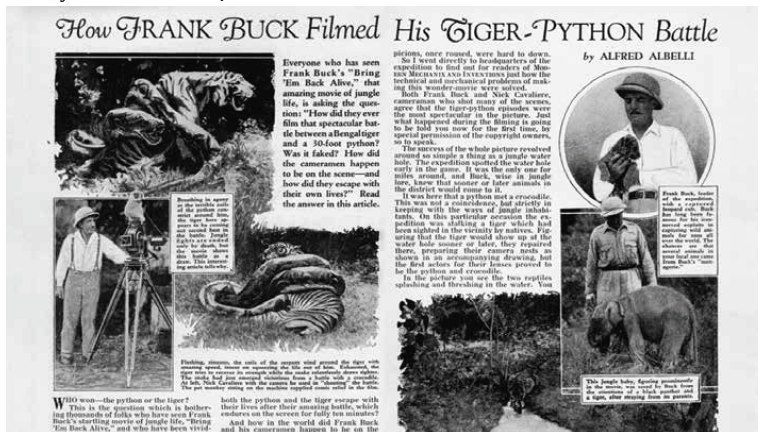

Bring ‘Em Back Alive was quite likely one of the more realistic films around, as Buck asserted, going by the detailed description of “How Frank Buck Filmed His Tiger-Python Battle” in an article from the American periodical, Modern Mechanix and Inventions. When interviewed, Buck and the main cameraman, Nick Cavaliere, explained how they studied the natural patterns of animal behaviour around a watering hole and lured a tiger into a forced encounter with a python.12

In their interview with American periodical, Modern Mechanix and Inventions, Frank Buck and the main cameraman, Nick Cavaliere, explained how they capitalised on normal patterns of animal behaviour around a watering hole to lure a tiger into a forced encounter with a python for one of the scenes. Their interview was published as “How Frank Buck Filmed His Tiger-Python Battle” in the November 1932 edition of the periodical.

In their interview with American periodical, Modern Mechanix and Inventions, Frank Buck and the main cameraman, Nick Cavaliere, explained how they capitalised on normal patterns of animal behaviour around a watering hole to lure a tiger into a forced encounter with a python for one of the scenes. Their interview was published as “How Frank Buck Filmed His Tiger-Python Battle” in the November 1932 edition of the periodical.There were many different levels of artifice involved in making Bring ‘Em Back Alive; the staged animal encounters were only one aspect. The other deception involved the locations where these scenes were shot. Viewers were led to believe that they were watching the action from the heart of the Malayan jungle when, in fact, the close-up scenes were shot along Jurong Road, just miles away from downtown Singapore.13

By providing a tropical location for the filming, Singapore became an essential component in creating the illusion of realism that had caught the attention of international audiences. Buck’s emphasis on a successful “illusion” and that “all pictures are made to entertain” made it clear that this form of filmmaking was of a different spirit from newsreels and documentary films.

Bring ‘Em Back Alive not only propelled Buck to stardom, but also thrust Malaya into the consciousness of international audiences. Many cinemas even displayed maps of Malaya alongside the film’s publicity posters. “At last, many people realised that Singapore is not in South Africa or China, or anywhere but where it is,” declared the director Elliott.14

Devil Tiger (1934)

Inspired by the success of Bring ‘Em Back Alive and the cinematic potential of Malaya, Clyde Elliott returned to Singapore in November 1932 with a Hollywood crew and cast led by rising star, Marion Burns, to film Man-Eater, “a Malayan talkie drama” for Fox Film Corporation (released in 1934 as Devil Tiger). While Bring ‘Em Back Alive was “a purely animal story”, Man-Eater moved one step further from documentary films with its dramatised storyline.15

Devil Tiger (1934), directed by Clyde Elliott, was the first Hollywood talkie produced in Singapore. The film featured well-known American stars such as Marion Burns and Kane Richmond. The Straits Times, 5 May 1934, p.

Devil Tiger (1934), directed by Clyde Elliott, was the first Hollywood talkie produced in Singapore. The film featured well-known American stars such as Marion Burns and Kane Richmond. The Straits Times, 5 May 1934, p.However, Man-Eater was not the first American feature drama to go on location in Singapore. Barely a month earlier, an American crew under the direction of Ward Wing and funded by the independent B. F. Zeidman Productions, with a script by the director’s wife Lori Bara, about a “simple native romance” set in a pearl diving community, had started filming Samarang (see text box below) in Singapore.16

These movies were part of a trend beginning in the late 1920s of “natural dramas” – scripted, fictional films – shot in exotic locations with a cast of local actors.17 Elliott’s progression from animal behaviour to human drama was mirrored by the career of fellow American filmmaker Ernest Schoedsack, whose biography and documentary film Rango (1931) provided the inspiration for the iconic movie King Kong (1933). The latter was written by Schoedsack’s long-time collaborator and friend, Merian Cooper.18

As a silent film by an independent production company, Ward Wing’s Samarang (1933) was quite different in scale from Devil Tiger. The latter was funded by a major studio, featured a well-known Hollywood cast, and most importantly, was the first talkie entirely produced in Malaya and Singapore.19 Elliott arrived in Singapore with eight tons of equipment, a cameraman, sound engineers, “three rising stars in Hollywood” – Marion Burns, Kane Richmond and Harry Woods – as well as a reporter from The New York Times. After the ignominious fallout with Frank Buck, this time around Elliott turned to a local Eurasian zoological collector, Herbert de Souza, for professional advice on the animal scenes.20 Many Caucasian residents in Singapore were cast as extras in genteel hotel party scenes.21

Numerous mishaps and accidents occurred during the course of the filming but these incidents were kept under wraps for fear of bad publicity. However, after the film’s release, it was revealed that the cameraman Jack Dunn was “mauled by a black panther”, and “Kane Richmond had two ribs fractured by a constricting python”.22

While American film reviewers described Devil Tiger as “thrilling”, “realistic” and “informative”, voting it as one of Fox Films’ best film offerings of 1934, the reaction back in Singapore was decidedly muted. Critics and audiences found the film forgettable and were nonplussed by the exaggerated portrayal of the Malayan jungle. One newspaper hack called it “a diverting melodrama of the forests” and “a picture worth seeing and enjoying, and forgetting”.23 Perceptions of realism and authenticity, and the value attached to these qualities were at odds with the portrayal of Singapore and the film’s target market on the other side of the globe.

Other filmmakers, however, expressed a desire for the kind of fully on location approach combined with Elliott’s prior experience of Malayan life that went into the making of Devil Tiger. In March 1936, the well-known travelogue producer, James A. Fitzpatrick, who was in Singapore to collect scenes and background for two films, said in an interview that he hoped to return to make a feature film: “It will have a plot drawn from the life of this unique city of the East. My stars I will bring with me. There will be no superimposing of plot or players against a pre-photographed Singapore background.” He also criticised the “over-coloured imaginations of ‘hokum’ writers who spend a few days here, then go back to the States and write of the gin-sling and champagne imbibing ‘beachcombers’ and such characters dear to the penny novelettes”.24

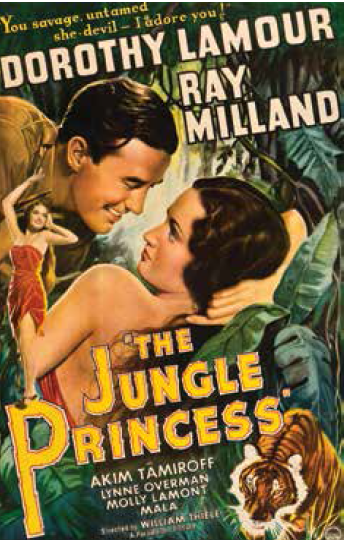

Despite the good reviews, Devil Tiger, however, failed to make its mark at the box office. That honour went to The Jungle Princess (1936), a Paramount Pictures film that was written and directed by William Thiele, and became the most successful film set in Malaya since Bring ‘Em Back Alive.25 The film also launched the career of Dorothy Lamour, who became known for her exotic sarong costumes in many Hollywood films, an image created by her role as a native girl in The Jungle Princess.

Although filmed in Hawaii, The Jungle Princess was the first talkie to use actual Malay dialogue, and reflected its supposedly multiethnic Malayan milieu by including characters who were clearly meant to be Chinese alongside Malay villagers and European hunters.26 Tightly directed and combining drama, comedy, romance and jungle action with captivating vocals by Lamour, the film played to full houses in Singapore. Unlike previous Malayan films, this one received the thumbs up from local critics.27 The Jungle Princess even inspired an Indonesian remake entitled Terang Boelan (1937), scripted by the Indonesian journalist Saeroen, with cinematography by an Indonesian Chinese, David Wong.28

The Jungle Princess (1936), starring Dorothy Lamour as a native girl, is the first talkie to use actual Malay dialogue. The story reflected multiethnic Malayan society by including a Chinese servant alongside Malay villagers and European hunters. Image source: Iceposter.com.

The Jungle Princess (1936), starring Dorothy Lamour as a native girl, is the first talkie to use actual Malay dialogue. The story reflected multiethnic Malayan society by including a Chinese servant alongside Malay villagers and European hunters. Image source: Iceposter.com.Booloo (1938)

Just months after the well-received release of The Jungle Princess, Paramount Pictures upped the ante with a similar tropical jungle romance-adventure filmed on location in Singapore. Booloo (1938) became Clyde Elliott’s third directorial outing in Malaya, after Bring ‘Em Back Alive and Devil Tiger.29 With 10 tons of “the most up-to-date, portable, light and sound equipment” this time, Elliott had more sophisticated tools and resources to work with on Booloo compared to his previous Malayan films.30

The story behind Booloo expresses most clearly the tension between realism and staged fiction. Although Elliott had been criticised for taking creative licence in Bring ‘Em Back Alive and Devil Tiger, with Booloo, he struggled to preserve authenticity in his film against commercial impositions from his bosses at Hollywood’s Paramount Studios. Like Samarang, Booloo was intended to feature local amateur actors from Malaya cast alongside the Paramount actor Colin Tapely.31

After an exhaustive search in which “girls from practically every class of Singapore society from Tanglin to Chinatown [were] given film tests”, a Javanese dancer named Ratna Asmara from the Dardenalla travelling performance troupe was eventually cast in the lead role of a Malay girl. Her Malay beau was played by a local Eurasian, Fred Pullen.32 Supporting roles were undertaken by other locals Elliott had worked with previously on Devil Tiger: Herbert de Souza, the aforementioned wildlife collector; Ah Ho, a Chinese male; and Ah Lee, a Chinese seven-year-old boy who played a minor role, as well as Europeans based in Singapore, such as the professional actor Carl Lawson, and two army officers.33

Many of the scenes in Booloo (1938) that featured a Malayan cast were eventually re-shot in Hollywood in order to make the film more appealing to its American audiences. The Straits Times, 18 July 1937, p. 5.

Many of the scenes in Booloo (1938) that featured a Malayan cast were eventually re-shot in Hollywood in order to make the film more appealing to its American audiences. The Straits Times, 18 July 1937, p. 5.With the casting of Ratna Asmara, it would seem that Booloo would achieve what both Samarang and The Jungle Princess could not – the role of a Malay protagonist played by an Asian actress speaking in her natural vernacular. But this was simply too real for American audiences to accept and, to Elliott’s dismay, most of his location shoots with the Malayan cast were left on the cutting-room floor.34 Paramount decided to reshoot most of the film in Hollywood and Ratna Asmara was replaced by the Hawaiian-American actress Mamo Clark of Mutiny on the Bounty (1935), in which she starred alongside the screen legend Clark Gable.35 If Dorothy Lamour had been convincing enough as a native Malay girl in The Jungle Princess, then casting a genuine native girl was of minor importance when compared to Mamo Clark’s celebrity status.

Hawaiian-American actress Mamo Clark replaced the Javanese dancer Ratna Asmara as the female lead in Clyde Elliott’s Booloo (1938) at the film editing stage. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Hawaiian-American actress Mamo Clark replaced the Javanese dancer Ratna Asmara as the female lead in Clyde Elliott’s Booloo (1938) at the film editing stage. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.While The Jungle Princess successfully recreated elements of Malaya in its Hawaiian setting, Booloo’s stronger attempt at realism failed to make it a better film. It never achieved the success of The Jungle Princess, instead receiving scathing reviews which panned its “silly story” and the “jungle and Hollywood sequences [which] have been spliced together so crudely”. Not even the Caucasian-looking Fred Pullen, acting as a Malay boy, passed the film editing, and only one of his scenes remained. Pullen was “extremely disappointed” and wrote to the producers to complain about his axing.36 Interestingly, Booloo was the last of the pre-war feature films to be shot in Singapore to receive an international commercial release.

The Real Singapore?

The portrayal of Singapore in these Hollywood films veered between fact and fantasy. They were shot on location, in tropical jungles to depict the habitat of wild animals in Bring ‘Em Back Alive, or a Malay village in Samarang. Whether accused of zoological “fakery” or showing a genuine Malay kampong in Bedok, both films were successful at the Singapore box office.37 The local setting and familiar faces seen on the big screen for the first time were enough to attract Singapore viewers, if only out of curiosity. The urban cinema-goers of Singapore who admired all things modern suddenly had rural village life presented to them in a new light.

Singapore also played into other stereotypes, as with the early seafaring and illicit romance-themed films that lacked authentic location footage. Various strategies were employed in the representation of Singapore as a bustling Asian urban centre, and attracted critical responses from local audiences. Alfred Hitchcock’s Rich and Strange (1931) included only brief street scenes of downtown Singapore, most likely taken from stock footage.38 In 1936, Tay Garnett filmed Singapore scenes for his film Trade Winds, to be used as rear projections for actors in a Hollywood studio, while Booloo went further in hiring over 200 extras – Malays, Chinese and Indian men, women and children, including “Chinese coolies and ricksha boys” – to film train scenes at the railway station.39

By March 1936, Singapore audiences had seen enough Hollywood versions of their island to invoke a scathing editorial in The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser. The writer bemoaned the “romanticising of our tropic city” and film directors who reinforce the stereotype of “Singapore as a tropical playground for its amorous and loose-moralled inhabitants”.

When Booloo was finally screened in Singapore, its valiant attempt at a realistic portrayal of Singapore urban life also came under fire. A letter to The Straits Times asked why the film was “trying to show the world that the Asiatic population of this city consists of nothing but hawkers, satai-men, poultry-farmers, ice-water sellers, pig rearers, and half-naked Chinese coolies”.40 The author, calling himself “No Hokum Here”, demanded to know if the authorities would “allow this sort of thing to be shown to the rest of the world”. Local audiences were astute enough to spot “fakery” as well as orientalist stereotypes in Western films.

Singapore was very much on Hollywood’s mental map of the world, but whether that impression was much like the real Singapore was questioned by its residents and cinema-goers.

Clyde Elliott managed to complete filming three feature films on location between 1932 and 1938, each time attempting a deeper, more realistic depiction of Malayan society. But realism was the least important factor when it came to the commercial aspirations of Hollywood studios. Attempts to depict Asian society more accurately failed to make it to the big screen, and misrepresentations of Singapore as a seedy maritime portof- call or where life-threatening jungle encounters were a regular occurrence continued. For audiences in Singapore, the release of these films was received with far less enthusiasm than the excitement of witnessing American cast and crew working on location during the films’ production.

SAMARANG (1933) SPARKS A FRENZY

Moving away from a jungle setting, Samarang (1933) was shot along the coast and offshore islands near Singapore. Filming began in October 1932 with a cast of local amateurs. The female lead – “Sai-Yu, beautiful daughter of the tribal chieftain” – was played by a local actress named Therese Seth, an amateur Eurasian dancer of Armenian ancestry who had been talent-spotted earlier. The male protagonist, a pearl diver named Ahmang, was played by an Englishman, Captain Albert Victor Cockle, who was Chief Inspector of Police and an amateur actor. His “exceptionally fine physique” led to comparisons with the Hollywood Tarzan star, Johnny Weissmuller.41

The director, Ward Wing, went to great lengths to make the movie convincing. Screen tests were held at which several bangsawan actors auditioned.42 He engaged extras from the Sakai tribe, “reputed to be cannibals”, to play the part of “natives” in spite of the difficulties involved:

Only one man could be found who could speak the Sakai language, but he was Chinese and knew no English, so a Malay who spoke Chinese was found, but he, in turn, could not speak English, so Wing had to tell an English-speaking Malay what he wanted. The Malay would tell the Malay speaking Chinese, who would tell the Chinaman, who would tell the Sakai!.43

Even the lead actor Cockle had to assist the director in translating instructions into Malay, while additional Tamil interpreters were hired for the Indian supporting cast members. No effort too was spared in maximising the dramatic potential of the natural surroundings. The underwater scenes of a real-life fight between a tiger shark and octopus, shot by cinematographer Stacy Woodward, were considered to be of important documentary value by experts in the US.44

Samarang (1933) was directed by Ward Wing, produced by United Artists and B. F. Zeidman, and distributed by United Artists. The female lead was played by a local Eurasian actress named Therese Seth, while the male protagonist was played by Captain Albert Victor Cockle, a British expatriate who was Chief Inspector of Police and an amateur actor. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Samarang (1933) was directed by Ward Wing, produced by United Artists and B. F. Zeidman, and distributed by United Artists. The female lead was played by a local Eurasian actress named Therese Seth, while the male protagonist was played by Captain Albert Victor Cockle, a British expatriate who was Chief Inspector of Police and an amateur actor. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

A review in The New York Times praised the film as “a picture distinguished by the obvious authenticity of many of its scenes. The flashes of the divers are shrewdly pictured – first by the men plunging into the sea and later by revealing them below, picking up shells. It is, of course, a fiction story to which a certain realism is lent by the portrayals by the natives”.45

The ethnographic details in parts of the film, particularly the opening scene filmed in a Malay kampong, provided a veneer of respectability for the risqué scenes featuring Cockle and Seth, who were clothed in the skimpiest of loincloths and flirted openly with each other. Although Seth wears a bikini top in this scene, for most of the 58 minutes of the rest of the film, she is topless.46

The film also inspired a mini-revolution in America. For the film’s opening in New York, the “Samarang Club” was inaugurated, “which provided that all its members should wear bathing shorts and not the complete costume”. At Californian seaside resorts, men flouted local laws and went swimming with bare chests, causing many of them to be hauled before the local magistrate. As members of clubs were exempt from such laws, many joined the Samarang Club.47

Passing for a quasi-documentary on natives of the South Seas, Samarang depicted the nude female body in a way that mainstream films set in Western society were not allowed to. The Pacific Islands and Bali, in particular, were popular locations for similar “nature dramas” with themes of sexuality. On-location filming and the use of a local amateur cast, even if the action was fictional rather than ethnographic documentation, was likely to have been the key to sneaking such salacious content past conservative elements in Hollywood and the American censors.

Chua Ai Lin was awarded the National Library’s Lee Kong Chian Research Fellowship in January 2015. This article is the condensed version of her research paper submitted as part of the fellowship.

Dr Chua Ai Lin is the president of the Singapore Heritage Society and a member of the National Library Advisory Committee. She holds a PhD in History from the University of Cambridge. Her papers on Singapore’s social and cultural history have been published in journals such as Modern Asian Studies and Inter-Asia Cultural Studies.

Dr Chua Ai Lin is the president of the Singapore Heritage Society and a member of the National Library Advisory Committee. She holds a PhD in History from the University of Cambridge. Her papers on Singapore’s social and cultural history have been published in journals such as Modern Asian Studies and Inter-Asia Cultural Studies.

NOTES

-

Singapore may become Hollywood of East. (1936, January 9). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The film invasion. (1936, March 20). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Millet, R. (2006). Singapore cinema (p. 19). Singapore: Editions Didier Millet. (Call no.: RSING q791.43095957 MIL); Millet, R. (2016, Apr–Jun). Gaston Méliès and his lost films of Singapore, 12 (1). Retrieved from BiblioAsia website; Toh, H.P. (n.d.). Singapore Film Locations Archive website. ↩

-

Millet, 2006, pp. 143–44.; Lai, C.K. (2001). The native in her place: Hollywood depictions of Singapore from 1940–1980. (Unpublished paper). Prints of these films are not easily available, with some existing only as non-circulating archival copies. The only print of Sal of Singapore, which is held in the UCLA library, is currently undergoing preservation and inaccessible to researchers, while the sole known copy of The Crimson City was rediscovered in the archives of the Museo del Cine in Buenos Aires, Argentina, in 2010. See Rohter, L. (2010, May 4). Footage restored to Fritz Lang’s ‘Metropolis’. The New York Times. Retrieved from The New York Times website. ↩

-

Slump in the tiger trade. (1932, September 21). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

$1,000,000 picture maker in Singapore. (1933, April 5). The Straits Times, p. 12; Wolfe, C. (1996). The poetics and politics of nonfiction: Documentary film (pp. 351–386). In T. Balio (Ed.), Grand design: Hollywood as a modern business enterprise, 1930–1939. History of the American Cinema, 5. New York: Scribner; Toronto: Collier Macmillan Canada; New York: Maxwell Macmillan International. (Call no.: LR 791.430973 HIS); The all-time best sellers. The 1937–38 Motion Picture Almanac (p. 942). New York: Quigley Publishing Company. Retrieved from Internet Archive website. ↩

-

The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 21 Sep 1932, p. 7; “Bring ‘Em back alive”. (1932, November 17). The Straits Times, p. 18. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Harry McGuire was writing in the magazine, Outdoor Life, as reported in The Straits Times, 17 Nov 1932, p. 18. See also Another critic of Mr. Frank Buck. (1933, April 9). The Straits Times, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Pictures and how they are made. (1932, December 8). The Straits Times, p. 16. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 5 Apr 1933, p. 12. ↩

-

When jungle gangsters meet. (1932, October 3). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Albelli, A. (1932, November). How Frank Buck filmed His tiger-python battle, pp. 34–41. Modern Mechanix and Inventions. Retrieved from Modern Mechanix website. ↩

-

In a press interview, Buck admitted that the close-up scenes were filmed in Jurong Road, Singapore. See The Straits Times, 5 Apr 1933, p. 12. He was also reported to have animal camps off Orchard Road, on the fringes of the downtown zone, and in the residential suburb of Katong. See Buck, F., & Fraser, F.L. (1941). All in a lifetime (p. 108). New York: R. M. McBride & company. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

The Straits Times, 8 Dec 1932, p. 16. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 8 Dec 1932, p. 16. ↩

-

“Out of the sea” off Singapore. (1932, October 9). The Straits Times, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG; Samarang was re-released in 1940 under the title The Shark Woman. See Millet, 2006, p. 143; Tan, B. (2015, Apr–Jun). From tents to picture palaces: Early Singapore cinema. BiblioAsia, 11 (1), 6–11, p. 10. Retrieved from BiblioAsia website. These movies were part of a trend beginning in the late 1920s of “natural dramas” – scripted, fictional films – shot in exotic locations with a cast of local actors. ↩

-

Deacon, D. (2006, March). Films as foreign offices: Transnationalism at paramount in the twenties and early thirties (p. 145). In A. Curthoys & M. Lake (Eds.), Connected worlds: History in transnational perspective. Canberra, Australia: ANU Press. Retrieved from National Australia University website; Heider, K.G. (2006). Ethnographic film (pp. 25–26). Austin: University of Texas Press. Retrieved from Open eClass website. ↩

-

Heider, 2006, p. 25; Geiger, J. (2013). Schoedsack, Ernest B. In I. Aitken (Ed.), The concise routledge encyclopedia of the documentary film. New York: Routledge. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Page 7 advertisements column 3: “Devil Tiger”. (1934, May 11). The Straits Times, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

“Man-Eater”. (1932, November 17). The Straits Times, p. 15. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Untitled. (1933, March 25). The Malayan Saturday Post, p. 14. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Deep mystery of “Man-Eater”. (1933, May 21). The Straits Times, p. 9; Notes of the day: “Devil” insects. (1934, May 23). The Straits Times, p. 10. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

“Devil Tiger” (1934, May 11). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG; Solomon, A. (2011). The Fox Film Corporation, 1915–1935: A history and filmography (p. 190). Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

New film of Singapore. (1936, March 20). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Geraghty, G., Hume, C. (Writers) & Thiele, W. (Director). (1936). The Jungle Princess [Movie]. Retrieved from IMDB website. ↩

-

Van der Heide, W. (2002). Malaysian cinema, Asian film: Border crossings and national cultures (p. 128). Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. (Call no.: RSEA 791.43 VAN). The Jungle Princess is also commercially available on DVD. ↩

-

“Jungle Princess” with a lisp. (1937, April 1). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 2; Page 7 advertisements column 1: “The Jungle Princess”. (1937, April 2). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 7; Page 7 advertisements column 2: “The Jungle Princess”. (1937, July 8). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Van der Heide, 2002, p. 128. ↩

-

Elliott, C.E. (Writer & Director). (1938). Booloo [Movie]. Retrieved from IMDB website. ↩

-

Real Malayan jungle for screen. (1937, July 18). The Straits Times, p. 5; Ten tons of film kit for jungle picture. (1937, August 17). The Straits Times, p. 13. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Untitled. (1937, August 5). The Straits Times, p. 12. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Movie cameras click in jungle. (1937, November 21). The Straits Times, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Dorothy Lamour type sought. (1937, August 5). The Straits Times, p. 12; “Booloo” girl not found yet. (1937, September 19). The Straits Times, p. 5; Australis, C. (1937, November 20). Notes of the day: Coy officers. The Straits Times, p. 10. Retrieved from NewspaperSG ↩

-

Fred Pullen protests to Hollywood. (1938, September 10). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Brady, T.F. (1942, May 24). Hollywood’s story marts dry up. The New York Times, p. X3. ↩

-

The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 10 Sep 1938, p. 9. ↩

-

Braddell, R.St.J. (1935). The lights of Singapore (p. 122). London: Methuen. (Call no.: RDKSC 959.57 BRA) ↩

-

Toh, H.P. (2013, January 18). Singapore is the MacGuffin: Location scouting in “Rich and Strange”. Retrieved from The Hunter website. ↩

-

The Straits Times,, 19 Sep 1937, p. 5. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 19 Sep 1937, p. 5. ↩

-

Samarang: Highlights of the film. (1933, September 29). Alhambra Magazine. (Not available in NLB holdings); Wright, N.H. (2003). Respected citizens: The history of Armenians in Singapore and Malaysia (p. 293). Middle Park, Vic.: Amassia Publishing. (Call no.: RSING 305.891992 WRI); Who’s Who in Malaya, 1939. (1939). Singapore: Fishers Ltd. (Call no.: RCLOS 920.9595 WHO); Thrills by Edgar Wallace. (1932, October 3) The Straits Times, p. 12. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Trial of Malay film talent. (1932, October 10). Singapore Daily News, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG ↩

-

Telling the world. (1933, September 20). Alhambra Magazine. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Pearl and shark story filmed here. (1932, December 1). The Malaya Tribune, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG; Mortal combat of tiger shark and octopus in “Samarang” is remarkable camera record. (1933, September 20). Alhambra Magazine. ↩

-

Hall, M. (1933, June 29). Dramatic adventures of a pearl diver featured in a film at the Rivoli. The New York Times. Retrieved from The New York Times website. ↩

-

Wing, W. (1933). Shark Woman, a.k.a. Samarang. Alpha Home Entertainment (Reprint in 2012). (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Wing, 1933; Shocked by bathers. (1934, March 18). The Straits Times, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩