Micro India: The Chettiars of Market Street

Market Street, in the heart of the business district, was where Indian moneylenders ran a thriving trade during the colonial era. Marcus Ng traces the imprint left by the Chettiars.

An 1890s photograph taken by G.R. Lambert of Market Street, which took its name from the nearby Telok Ayer Market. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the street was well known for its community of Chettiars, who ran their moneylending business in kittangi − shophouses which served as both their offices and lodgings. Lee Kip Lin Collection. Lee Kip Lin and National Library Board, Singapore.

An 1890s photograph taken by G.R. Lambert of Market Street, which took its name from the nearby Telok Ayer Market. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the street was well known for its community of Chettiars, who ran their moneylending business in kittangi − shophouses which served as both their offices and lodgings. Lee Kip Lin Collection. Lee Kip Lin and National Library Board, Singapore.As a boy, Lakshmanan Subbiah, a fourth-generation Chettiar, recalls walking down a street in the heart of the city near Raffles Place, a stroll that brought him past a mosque, where the cry of the muezzin1 would herald a throng of men in sarongs and skullcaps rushing to prayer.2 At the end of the road, towards the river, entrenched in the corner of a stately colonial building,3 moneychangers could be heard hollering, “US dollars, pounds, US dollars….”

As Subbiah forded a small crossing, the scene changed to rows of shophouses – not the familiar coffeeshops, traditional medicine halls and clan associations of Telok Ayer,4 but a different blend of sights, smells and sounds: the sharp fragrance of cinnamon and cardamom; the pungent bite of garlic and onions; aisles of silk sarees spilling onto the “five-foot way”; curries and chutneys splashed across banana leaves; and the dust of urban mills as grains, grams5 and raw spices were ground into flour, pastes and finer mixtures.

Amid these louder establishments were half a dozen more austere premises: communal offices called kittangi (derived from “warehouse” in Tamil), which served as both bank and bunk for the men who lived and worked in them. “There, you would see some shaven Indian men, sitting on the floor by low desks, bent over and writing on open ledgers with total concentration,” recounts Subbiah.

These men were Chettiars from Chettinad in India’s Tamil Nadu state, a caste of Tamil moneylenders (and devotees of Lord Siva6) who served as vital links in the entrepreneurial food chain in times past when capital and credit were scarce, and big international banks7 catered largely to commercial trading houses – having little time for small local businessmen with neither capital nor collateral.

A 1960 photo of three Chettiars inside a kittangi at 49 Market Street. Nachiappa Chettiar Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

A 1960 photo of three Chettiars inside a kittangi at 49 Market Street. Nachiappa Chettiar Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.This was a niche in Singapore’s financial sector that was begging to be filled, and the Chettiars did just so for a century-and-a-half, providing sundry merchants and middlemen with the funds they needed to fuel the port’s early growth as a pit-stop in the opium route between the Bay of Bengal and the South China Sea, and later as a global emporium for tin, rubber and other tropical commodities.8

Though still vivid in Subbiah’s memory, these kittangi, along with an entire community of South Asian businesses centred around Market Street, vanished in 1977 when the entire quarter was redeveloped into a multi-storey complex named after the Golden Shoe – the old, and no doubt propitious, label for Singapore’s financial district.9 Today, the only vestige of old Market Street, which served as the main artery of Micro India (a moniker coined by Subbiah as a nod to Serangoon Road’s “Little India”), is Masjid Moulana Mohamed Ali, a mosque of Indian Muslim origin in the basement of UOB Plaza. The muezzin no longer calls at prayer time, but a bargain struck with the bankers has ensured that a room for prayer remains in a zone dedicated to worldly gains.10

From Madras to Market Street

Market Street first appeared in a town plan by Lieutenant Philip Jackson published in 1828, which shows the road ending at the original Telok Ayer Market facing Telok Ayer Bay.11 In 1894, due to reclamation works that pushed the shoreline farther, the market (better known as Lau Pa Sat today) was relocated to its present site.12 Locals, however, dubbed this thoroughfare Chetty theruvu or “Chetties’ Street” after the Chettiars who, along with other South Asian migrants, had established one of modern Singapore’s first Indian settlements here by the 1820s.13 The road was also known as Tiong koi (“Central Street”) or Lau pa sat khau (“Old market mouth”) to the Hokkiens, who maintained a long presence in the area as importer-exporters and commission agents.14

By Subbiah’s reckoning, Market Street had, in its heyday, as many as seven kittangi, and housed some 300 to 400 Chettiar firms. As recently as the 1970s, when the Chettiars were already losing ground to homegrown banks, Market Street still had six kittangi as well as 30 to 40 Indian-owned businesses. Nearly 500 people (about half of whom were Chettiars) called the area home, for the kittangi doubled as dorms. Each proprietor leased a few square feet of floor space along a narrow hallway, just enough to store a cupboard, a safe and a chest that also served as a table where the Chettiar met customers and balanced his books. Come evening, a cook dished out meals from a kitchen at the rear, and before turning in, the bankers rolled out mattresses for a spartan sleep-in before the next trading day.

In Chettinad, the Chettiars are known as the Nattukottai Chettiars (“people with palatial houses in the countryside”). The word Chettiar is derived from chetty, the Tamil translation of shreshti, the Sanskrit word for “merchant”. Though few families in Chettinad today have the means to maintain their mansions, many of these dwellings still survive in inland villages, a geographical anomaly Subbiah traces to a likely tsunami that destroyed the Chettiars’ original maritime bases some 700 years ago, leading the community to avoid coastal settlements thereafter. Oral traditions suggest that Chettiars were already trading with Southeast Asia some 2,000 years ago.15 Much later, when the British established a foothold in Madras (now Chennai) in 1644, they found willing and able business partners in the Chettiars, who followed in the wake of the East India Company as ports were established in Ceylon, Calcutta, Penang, Melaka, Singapore, Burma, Vietnam and Medan.16

A studio shot of RM. V. Supramanium, great-grandfather of Lakshmanan Subbiah, 1920. Nachiappa Chettiar collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

A studio shot of RM. V. Supramanium, great-grandfather of Lakshmanan Subbiah, 1920. Nachiappa Chettiar collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.In the wild west economic environment of early Singapore, when few European banks were willing to risk malaria and pirates to set up shop at Commercial Square (now Raffles Place), the Chettiars offered much-needed liquidity to local merchants, opium traders, miners, planters, contractors and petty traders. Even civil servants and Malay royalty were known to have sought out the kittangi in order to finance their big-ticket purchases.17

Thanks to their long-standing commercial ties with the British in India, the Chettiars were among the few non-Europeans with sufficient clout to obtain credit at favourable rates from European financial establishments. “They would borrow the money, come to Market Street and give it out as small loans,” explains Subbiah, who grew up in one of Market Street’s kittangi and now works as a financial controller in a multinational firm. Little or no collateral was sought, so interest rates of 24 to 36 percent (as high as 48 percent during World War II) were charged, and the Chettiar took pains to personally appraise each potential borrower and his credit-worthiness.

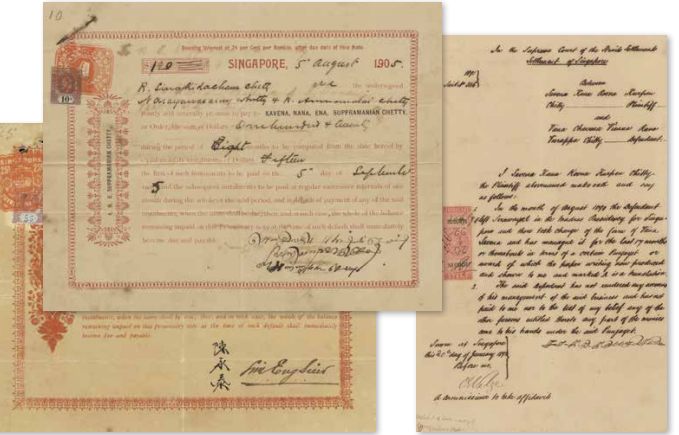

Chettiar legal documents provide a glimpse into the business practices of the Chettiars. Clockwise from left: A promissory note, bearing interest at 24 percent per annum, to be paid in equal monthly instalments; failure to pay any one instalment would render the entire sum due and payable. (Title ID: 040000500); affidavit by the plaintiff in a suit where the defendant had been appointed to manage the plaintiff’s firm but failed to render the accounts (Title ID: 170005179); and a promissory note (partially hidden) bearing interest at 24 percent per annum (Title ID: 040000506). Koh Seow Chuan Collection, National Library, Singapore.

Chettiar legal documents provide a glimpse into the business practices of the Chettiars. Clockwise from left: A promissory note, bearing interest at 24 percent per annum, to be paid in equal monthly instalments; failure to pay any one instalment would render the entire sum due and payable. (Title ID: 040000500); affidavit by the plaintiff in a suit where the defendant had been appointed to manage the plaintiff’s firm but failed to render the accounts (Title ID: 170005179); and a promissory note (partially hidden) bearing interest at 24 percent per annum (Title ID: 040000506). Koh Seow Chuan Collection, National Library, Singapore.“It was a simple, non-bureaucratic process,” recalls Subbiah. Visiting a kittangi, where one was greeted and served by a (usually) shirtless man in a white dhoti and vibuthi-smeared forehead18 who was conversant in Tamil and Malay, was no doubt a far less intimidating, and likely more fruitful, experience for the average towkay than having to brave the stiff regard of colonial banks. Indeed, until the 1970s, it was said that “many a successful Chinese towkay began his climb on a loan from a Chettiar”.19

An undated image of a bare-chested Chettiar moneylender with holy ash smeared across his forehead (likely from the 1950s or 60s). He is pictured at his work desk. Sharon Siddique Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

An undated image of a bare-chested Chettiar moneylender with holy ash smeared across his forehead (likely from the 1950s or 60s). He is pictured at his work desk. Sharon Siddique Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.Throughout the 19th century and much of the early 20th, Chettiars across Southeast Asia acted as full service bankers, providing liquidity in the form of working capital loans, syndicated loans, investment capital and demand drafts. These injections of capital helped to drive trade wherever they settled: coconut, rubber, coffee and tea in Ceylon; rice, gems and teak in Burma; tin, rubber and rice in Malaya; rice in Vietnam; and sugar in South Africa and Mauritius.

The Rise and Decline of the Chettiars

As a community, the Chettiars punched far above their demographic weight. In the 1920s, the Chettiars were reported to have amassed about 1.2 billion rupees in wealth, despite numbering no more than 30,000 worldwide. There were never sizable communities of Chettiars at any one Asian outpost; the typical Chettiar undertook a series of three-year sojourns in a foreign port before returning to his ancestral village with the funds to build a vast mansion for his extended family and assume the role of patron of culture and the culinary arts. (The rich Chettinad food of Tamil Nadu, notes Subbiah, gained its fame from the patronage of Chettiars.) The Chettiar tour of duty was largely the province of bachelors; young boys often accompanied their elders as apprentices, and only after the 1950s did Chettiar womenfolk join their male kin in the Malay Peninsula.20

The close-knit, almost insular, nature of overseas Chettiar communities, a source of mutual strength in colonial times, was to prove a liability in the mid-20th century, when the Great Depression and a growing wave of nationalism turned the tide against these expatriate bankers. “They were making huge amounts of profit and sending it all back to India,” observes Subbiah. “They didn’t invest anything locally because they were sojourners.”

Never populous nor politically powerful – but closely associated with British overlords, and perceived as Shylocks21 who drained economies of their surpluses – the Chettiars became easy targets in the post-war years. When boom turned to sustained bust, widespread defaults by clients and the consequent takeover of borrowers’ assets rewarded the Chettiars with vast tracts of land and property across Southeast Asia. In Lower Burma, Chettiars were reported to have controlled between a quarter to nearly half of all productive land in 1937.22 When the nationalists assumed power, first in Rangoon, then in Colombo, Saigon and Jakarta, the Chettiars had their possessions nationalised and were given marching orders. “Some walked back across the border,” says Subbiah of this enforced exodus.

Only in Malaya did the Chettiars emerge relatively unscathed. But even in Singapore, the tea leaves bode ill as the island embarked on a post-colonial trajectory. From the 1950s, greater regulation of banks and moneylenders reduced official interest rates to unprofitable margins, although some borrowers sweetened the deal with off-the-record mark-ups. As Singapore prepared to enter an era of internal self-rule in 1959, there were fears of a looming socialist regime similar to those in Indochina and Burma.23 Many Chettiars called in their options, and sold their properties and other assets before returning to India for good. For those who remained and found a nation that veered neither left nor right along the ideological scale, the advent of easy credit and new domestic players in the 1970s chipped away at their historical dominance as bankers to small-to-medium enterprises.24

By the mid-1970s, the Chettiars found themselves in an unusual position. Although their business was dwindling, they still owned much land and enjoyed financial strength. So when the government asked the community to redevelop their properties around Market Street into modern buildings either individually or jointly with local banks, they agreed, fearing in part that the alternative was to have their land forcibly acquired or nationalised.

The kittangi were sold for a song and many older Chettiars called it a day, selling off all their properties in Singapore to carve a comfortable retirement in their homeland. Others moved to premises at Cantonment Road, Serangoon Road and Tank Road, where a lone kittangi still holds fort in the shadow of Sri Thendayuthapani (more popularly known as Chettiars’ Temple). Established in 1859, this shrine is probably the most significant landmark associated with the Chettiars, who erected temples to Lord Murugan wherever they went.25 For most Singaporeans, the Tank Road temple is better known as the end point of the annual Thaipusam procession, perhaps the only tangible manifestation of Chettiar religious culture in the Singapore mindscape.

Members of the Chettiar community at the entrance of the Sri Thendayuthapani Temple at Tank Road (Chettiars’ Temple), c.1930s. Nachiappa Chettiar Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Members of the Chettiar community at the entrance of the Sri Thendayuthapani Temple at Tank Road (Chettiars’ Temple), c.1930s. Nachiappa Chettiar Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.“It was the end of an era,” declares Subbiah. Shorn of their downtown enclave and with surviving kittangi sidelined, “the old communal life was over”. For a time, the local Chettiar community dwindled to as few as 30 families, before a new wave of migrants from Tamil Nadu from the 1990s onwards, mostly engineers or IT professionals, bolstered their numbers to the present thousand or so. Back in India, enterprising Chettiars had long diversified, becoming industrialists, manufacturers, publishers and owners of Tamil film studios. But other members of the community floundered in the post-colonial era, lacking both capital and formal education. To make ends meet, they sold their heirlooms and once-palatial homes, while younger Chettiars settled into new roles as professionals and entrepreneurs.

A Forgotten Street

With the demise of Market Street’s kittangi and other shophouses, the city lost what Subbiah called a neighbourhood “with a clear identity as an Indian area”. This “Micro India” of his childhood, he adds, consisted of Tamil Hindu as well as Muslim establishments along with North Indian and Chinese businesses. “In that sense I think it was a real ‘Little India’ – much more so than even Serangoon Road today,” he declares.

In the early 1970s, Market Street was a one-stop shop where local Indians would spend a day out, perhaps settling accounts with their Chettiar before visiting a barber or saree dealer, stocking up on provisions, lunching at a banana leaf restaurant, and spending the remaining daylight hours at the waterfront. “The waves used to come up all the way,” recounts Subbiah of a time when the Singapore River emptied into the open strait, before the sea was tamed and fenced in by an urban bay. “People walked over to the Esplanade, they’d buy peanuts and balloons, lie down and relax, and then at sunset they’d go back.”

Chettiar men posing for a photograph in front of the Mercantile Bank in Raffles Place, 1960. Nachiappa Chettiar Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Chettiar men posing for a photograph in front of the Mercantile Bank in Raffles Place, 1960. Nachiappa Chettiar Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.Other than the Chettiars, Market Street was an “incubator” site for other Indian as well as non-Indian enterprises. Subbiah recalls being asked by his elders to buy tea from a young wallah named Mustaq Ahmad, who helped his father man a pushcart at a corner of Market Street and Battery Road before going on to helm the outfit now known as Mohamed Mustafa & Shamsudin.26 Textile retailer Second Chance occupied a shop lot along Chulia Street in the 1970s, while the headquarters of PGP, a chain of provision stores owned by philanthropist P. Govindasamy Pillai, was located on the upper reaches of Market Street.27

Tat Lee Bank28 had its headquarters, as well as an iron and steel rolling mill, between two kittangi, while various law firms and shipchandlers operated from Chulia (previously Kling) Street, now a mere laneway unlike its sprawling namesake in Georgetown, Penang. Along Malacca Street, the Portuguese Mission owned the neoclassical Nunes Building, designed by Swan & Maclaren29 with decorative panels on its façade by Italian sculptor Cavalieri Nolli,30 next to which stood the offices of the Lee & Lee legal firm between 1955 and 1969.31 Market and Malacca streets also housed the spice trading business of the Jumabhoys from Gujarat, which later expanded into Scotts Holdings.32

For the young Subbiah, these luminaries were probably mere footnotes, fleeting faces and impressions preserved amid memories of Market Street and playing football on Raffles Place green33 after the city was deserted by its workers early in the evening. “The kittangi was a fun place to stay,” he muses. Market Street was also part of the route taken by traditional Chingay revellers before the parade took on a less pugilistic turn.34 To this day, a kavadi procession known as Punar Pusam (see text box below), which begins at the Sri Layan Sithi Vinayagar Temple at Keong Saik Road and ends at Tank Road on the evening before Thaipusam, passes Market Street on its annual circuit.

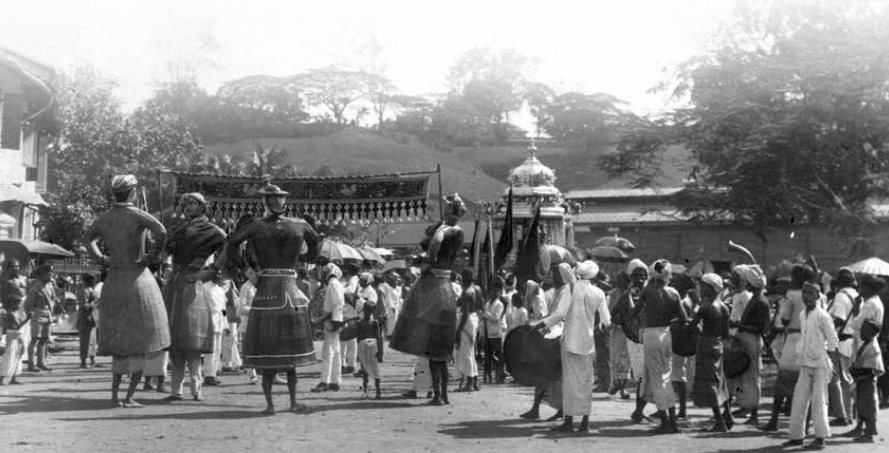

Punar Pusam procession with traditional stilt-walkers, and Fort Canning in the background (c. 1920s−30s). This lesser known annual procession takes place on the eve of Thaipusam. Early in the morning, the chariot bearing Lord Murugan leaves Chettiars’ Temple at Tank Road for Sri Layan Sithi Vinayagar Temple at Keong Saik Road. The chariot then returns to Tank Road in the evening accompanied by a retinue of kavadi bearers and passing Market Street along the way. Courtesy of Lakshmanan Subbiah.

Punar Pusam procession with traditional stilt-walkers, and Fort Canning in the background (c. 1920s−30s). This lesser known annual procession takes place on the eve of Thaipusam. Early in the morning, the chariot bearing Lord Murugan leaves Chettiars’ Temple at Tank Road for Sri Layan Sithi Vinayagar Temple at Keong Saik Road. The chariot then returns to Tank Road in the evening accompanied by a retinue of kavadi bearers and passing Market Street along the way. Courtesy of Lakshmanan Subbiah.Another occasion that sticks in Subbiah’s mind is a different assembly that took place upon the death of Mao Zedong, founding father of the People’s Republic of China, on 9 September 1976. News of this saw Market Street thronging with people all the way to the Bank of China building on Battery Road (then one of the few local conduits to the People’s Republic of China), prompting the curious boy to join the crowd and ink a note in a condolence book in the Chinese bank. “I was 12 years old; I can’t even remember what I wrote,” Subbiah quips. “Everyone was signing and when it was my turn, I couldn’t even reach the book so the man behind me lifted me up.”

“Memory’s images, once they are fixed in words, are erased,” observed Marco Polo in Invisible Cities, Italo Calvino’s fable on the eternal yet ephemeral nature of place making. But it could also be argued that the very act of remembering is one that resists decay and deconstruction – in this case the literal tearing-down of spaces to which incomes, and identities, were tethered. For Singapore’s Micro India, this is perhaps all that remains, as the Chettiars bid farewell to homes that doubled as offices and retreated from the frontlines of commerce into the margins of living memory.

OF FAITH, ON FOOT: THE PUNAR PUSAM PROCESSION

Many are familiar, or at least acquainted, with the annual Thaipusam procession that begins at Sri Srinivasa Perumal Temple along Serangoon Road and ends at Chettiars’ Temple at Tank Road. This procession, dominated by believers who bear elaborate kavadi35 as a visible sign of their devotion, takes place on the full moon of the Tamil month of Thai, which falls in January or February each year.

Few, however, have any inkling that on the eve of Thaipusam, an equally hallowed procession commences late in the day from the Sri Layan Sithi Vinayagar Temple at Keong Saik Road. Known as Punar Pusam or Chetty Pusam, this march involves kavadi bearers from the Chettiar community who wind their way through Chinatown, the Central Business District and City Hall.

On the eve of Thaipusam, the Punar Pusam or Chetty Pusam procession, which involves kavadi bearers from the Chettiar community, commences late in the day from the Sri Layan Sithi Vinayagar Temple at Keong Saik Street and winds its way through Chinatown, the Central Business District and City Hall, before ending at the Thendayuthapani Temple (Chettiars’ Temple) at Tank Road. Photo by Marcus Ng taken at Keong Saik Street on 8 February 2017.

On the eve of Thaipusam, the Punar Pusam or Chetty Pusam procession, which involves kavadi bearers from the Chettiar community, commences late in the day from the Sri Layan Sithi Vinayagar Temple at Keong Saik Street and winds its way through Chinatown, the Central Business District and City Hall, before ending at the Thendayuthapani Temple (Chettiars’ Temple) at Tank Road. Photo by Marcus Ng taken at Keong Saik Street on 8 February 2017.

For the Chettiars, Punar Pusam commemorates the only time of the year when Lord Murugan leaves the Tank Road temple. Borne in a silver chariot, Lord Murugan first visits his elder brother Lord Ganesha at Sri Layan Sithi Vinayagar Temple, before returning in the evening by way of Sri Mariamman Temple,36 abode of the Mother Goddess of South Indian Hindus. In the past, the chariot, accompanied by a human chain of kavadi bearers, would meander along Robinson Road, D’Almeida Street and Market Street, where Lord Murugan would give his blessings to the Chettiar businesses in the area. The kittangi are long gone, but the entourage still pauses to dance and whirl before the landmarks of their faith and forefathers, and in the shadow of their financial heirs, the modern towers housing the Indian Bank and Indian Overseas Bank.

A lorry pulls the deity today; there are no more bullocks for the task. Neither are there stilt-walkers, clowns in costumes and musical bands, which in times past cheered the marchers on and brought the town to a halt with pomp and ceremony. According to Lakshmanan Subbiah, a fourth-generation Chettiar, the Chettiars would even pay for the trams along South Bridge Road to stop for a few hours so that the road was clear for the procession. Before the war, fireworks were de rigueur. And until Dhoby Ghaut was dug up, the chariot also stopped by a shrine to Lord Siva at Orchard Road37 before the final leg towards Tank Road.

A 1920s photograph of a bullock-drawn silver chariot bearing a statue of Lord Murugan during the annual Punar Pusam procession. Gwee Thian Hock Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

A 1920s photograph of a bullock-drawn silver chariot bearing a statue of Lord Murugan during the annual Punar Pusam procession. Gwee Thian Hock Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Accompanied by families and well-wishers, and under the watchful eyes of minders and police outriders, the devotees today take up a mere lane or slightly more. For the most part, the city rushes on in its usual headlong fashion as the procession snakes past, as if bystanders eschew the power of faith, or are unwilling to indulge in the vague rites of a forgotten migrant community. The kavadi cavalcade continues on regardless, through dust and rain, sweat and stain, on bare soles and to the encouragement of pipes and drums. Dusk turns to dark and the streets ring with the steps of the kavadi carriers, telling of their story, strength and spirit.

A version of this article was first published on Poskod.sg on 24 January 2014.

Marcus Ng is a freelance writer, editor and curator interested in biodiversity, ethnobiology and the intersection between natural and human histories. His work includes the book Habitats in Harmony: The Story of Semakau Landfill (2009 and 2012), and two exhibitions at the National Museum of Singapore: “Balik Pulau: Stories from Singapore’s Islands” and “Danger and Desire”.

Marcus Ng is a freelance writer, editor and curator interested in biodiversity, ethnobiology and the intersection between natural and human histories. His work includes the book Habitats in Harmony: The Story of Semakau Landfill (2009 and 2012), and two exhibitions at the National Museum of Singapore: “Balik Pulau: Stories from Singapore’s Islands” and “Danger and Desire”.

NOTES

-

The person appointed at a mosque to lead and recite the call to prayer. ↩

-

This would have been Masjid Moulana Mohamed Ali, which was established in two Market Street shophouses in the 1950s to serve Muslims working in the commercial centre. See Masjid Moulana Mohamed Ali. (2015). Retrieved from Masjid Moulana Mohamed Ali website. ↩

-

This was Bonham Building (now the site of UOB Plaza), the original headquarters of United Overseas Bank. See Lim, T.S. (2016, October– December). As good as gold: The making of a financial centre. BiblioAsia, 12 (3), 17–23, p. 21. Retrieved from BiblioAsia website. ↩

-

Meaning “Water Bay” in Malay, Telok Ayer has become synonymous with Singapore’s Chinatown. ↩

-

Grams refer to pulses such as black grams (used in South Indian staples such as idli and thosai), lentils and chickpeas. ↩

-

Saivites, who revere Lord Siva as the Supreme God, and Vaishnavites, who revere Lord Vishnu, form two major branches in the Hindu religion. ↩

-

Early banks around Raffles Place such as Union Bank of Calcutta (1840); Chartered Mercantile Bank of India and China (1856); Chartered Bank of India, Australia and China (1861); Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corporation (1877) and Asiatic Banking Corporation (1860s) would have provided finance mainly to large European trading houses. See National Library Board. (2018). Raffles Place written by Cornelius, Vernon. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia website. ↩

-

It was reported that by 1867, “most of the Singapore opium trade passed through their (Chettiar) hands”. See Mahadevan, R. (1976). The pattern of enterprise of immigrant entrepreneurs in the overseas – A study of the Chettiars in Malaya 1880–1930. Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, 37, 446–456, pp. 448–449. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

Chua, B.H., & Liu, G. (1989). The Golden Shoe: Building Singapore’s financial district. Singapore: Urban Redevelopment Authority. (Call no: RSING 711.5522095957 CHU) ↩

-

Masjid Moulana Mohamed Ali moved to the basement of UOB Plaza after the trustees accepted an offer to accommodate the mosque after the bank acquired the Market Street shophouses for redevelopment. See Yang, W. (1981, February 21). Mosque in basement if offer taken. The Straits Times, p. 17. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Survey Department, Singapore. (1828). Plan of the Town of Singapore by Lieut Jackson. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Lee, K.L. (1983). Telok Ayer Market: A historical account of the market from the founding of the settlement of Singapore to the present time (unpaged). Singapore: Archives & Oral History Dept. (Call no.: RSING 725.21095957 LEE) ↩

-

Sandhu, K.S., & Sandhu, K.K. (1969, September). Some aspects of Indian settlement in Singapore, 1819–1969. Journal of Southeast Asian History, 10 (2), 193–201, p. 197. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

Savage, V.R., & Yeoh, B.S.A. (2013). Singapore street names: A study of toponymics (pp. 248– 250). Singapore: Marshall Cavendish Editions. (Call no.: RSING 915.9570014 SAV) ↩

-

Thinappan, S.P., & Vairavan, S.N. (2010). Nagarathars in Singapore (p. 15). Singapore: Navaso. (Call no.: RSING 305.89141105957 THI) ↩

-

Muthiah, S., et al. (2000). The Chettiar heritage (p. vii). Chennai: The Chettiar Heritage. (Call no.: R 954.089 CHE) ↩

-

Sandhu & Sandhu, Sep 1969, p. 199. The extent of loans to Malay royalty is illustrated by Winstedt who records that “in 1862 being heavily indebted to a Kavana Chana Shellapa Chetty, Sultan Ali [of Singapore] gave this Tamil money-lender the right to sell Muar to the British or the Temenggong of Johor.” See Winstedt, R.O. (1932). A history of Johore: 1365–1895 A. D (p. 113). Singapore: Singapore Printers, Ltd. (Call no.: RRARE 959.5142 WIN; Microfilm no.: NL 1577) ↩

-

Vibuthi is the holy ash applied on the foreheads of Saivite Hindus to honour Lord Siva. ↩

-

Sandhu & Sandhu, Sep 1969, p. 199. ↩

-

Thinnappan & Vairavan, 2010, p. 33. ↩

-

Shylock, an avaricious Jewish moneylender, is a character in William Shakespeare’s play, The Merchant of Venice. ↩

-

Adas, M. (1974, May). Immigrant Asians and the economic impact of European imperialism: The role of the South Indian Chettiars in British Burma. Journal of Asian Studies, 33 (3), 385–401, p. 400. Retrieved from JSTOR NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

Ministry of Culture. (1964, August 16). Transcript of the prime minister, Mr Lee Kuan Yew’s speech at the political study centre on 16th August, 1964 in connection with the seminar on “the concept of democracy” organised by the joint committee for radio courses [Speech]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Thinnappan & Vairavan, 2010, p. 25. ↩

-

Lord Murugan, also known as Sri Thendayuthapani, is a son of Lord Siva and the principal deity at the Chettiars’ Temple. Over a 150-year period, the Chettiars are estimated to have built about 105 temples in Southeast Asia: 59 in Burma, 25 in Ceylon, 18 in Malay, and one each in Vietnam, Singapore and Medan. ↩

-

National Library Board. (2016). Mohamed Mustafa and Samsudin Co Pte Ltd written by Nureza Ahmad & Noorainn Aziz. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia website. ↩

-

See Boo, K. (1999, September 24). End of an era. The Straits Times, p. 47. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Tat Lee Bank opened at Market Street in 1974 and merged with Keppel Bank in 1998. ↩

-

T. F. Hwang takes you down memory. (1988, June 25). The Straits Times, p. 22; Colony cavalcade. (1936, April 26). The Straits Times, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Materials used in constructing Nunes and Medeiros. (1937, October 5). The Straits Times, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG; Davison, J. (2017, Jul–Sep). Swan & Maclaren: Pioneers of Modernist architecture. BiblioAsia, 13 (2), 24–31, p. 28. Retrieved from BiblioAsia website. ↩

-

Lee & Lee. (2017). Retrieved from Lee & Lee website. ↩

-

Jumabhoy, R. (1982, August 7). The spice trade article and my family. The Straits Times, p. 17. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Raffles Place was converted to house an underground carpark in 1961 and became a pedestrian zone in 1972. See National Library Board, 2018. ↩

-

Sam, J. (1985, February 24). Fiery start to 1830 lunar year. Singapore Monitor, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The kavadi is a semi-circular metal structure decorated with peacock feathers, flowers and palm leaves, which devotees carry during the Thaipusam procession, often in fulfilment of a vow. See Hindu Endowments Board. (2016). Thaipusam. Retrieved from Hindu Endowments Board website ↩

-

Soundararajan, A., & Sri Asrina Tanuri. (2016, October–December). Time-honoured temple design. BiblioAsia, 12 (3), 36–39, p. 36. Retrieved from BiblioAsia website. ↩

-

This was the Sri Sivan Temple at Dhoby Ghaut, which was relocated to Geylang East to make way for the MRT station in 1983. See Hindu Endowments Board. (2016). Sri Sivan Temple. Retrieved from Hindu Endowments Board website. ↩