Maiden Lim and Her Sisters: Taoist Folk Goddesses of Singapore

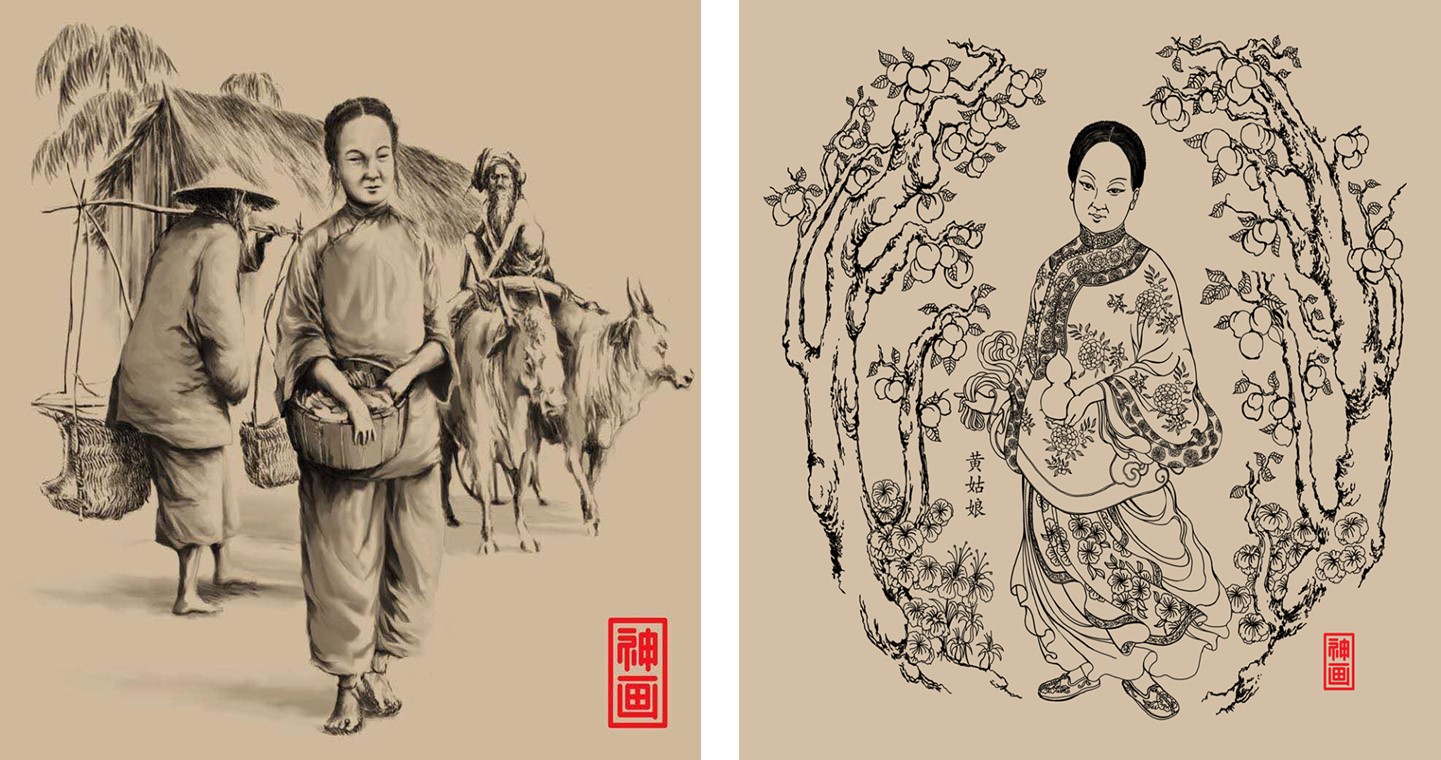

The local Taoist pantheon includes goddesses only found in Singapore, such as Lin Guniang, Lei Niangniang and Huang Guniang.

By Ng Yi-Sheng

In the 1960s, my father lived in mortal fear of the goddess Lin Guniang (林姑娘).1 As a child living in Kampong Henderson, he knew her by her Hokkien name, Lim Kor Niu. While he often passed by her shrine on Henderson Road, he never dared to gaze at her statue.

“People said the place was haunted,” my father told me. “We’d be damn frightened. You’d pass by, but you wouldn’t look.”2 He recalled that the shrine was tiny, fitting six people at most, with wooden walls and a gabled roof made of zinc or attap. It stood beside a tree, with a joss stick holder and a table outside. Alongside there was a storm drain with a stone bridge linking the site to the road.

The goddess was well-known in the neighbourhood. Residents referred to the lower stretch of Henderson Road between Tiong Bahru Road and Alexandra Road as “Lim Kor Niu” and even nicknamed a nearby hawker stall “Lim Kor Niu Char Kway Teow”. Yet somehow, over time, memory of the goddess has faded. Today, even among Singapore heritage enthusiasts, her name is largely unknown.

This is a shame. Lin Guniang – also known as Hongshan Lin Guniang (红山林姑娘), or Maiden Lim of Redhill – is an example of a uniquely Singaporean Taoist folk goddess. Her legends and ritual traditions began not in China, Hong Kong or Taiwan, but on this very island.

The notion of a homegrown goddess may sound bizarre. In fact, several such deities exist. By far the most famous is the German Girl of Pulau Ubin, also known as Nadu Guniang (拿督姑娘), recently written about by William L. Gibson for BiblioAsia.3 Photographer Ronni Pinsler has documented at least half a dozen more on his Facebook group “Local Gods & Their Legends”4 and on his website, “The Book of Xian Shen”.5

In this essay, we will look at three homegrown goddesses, all based in the heartland of Singapore’s south. Their names are Lin Guniang, Lei Niangniang and Huang Guniang. Together, they have been dubbed by Taoist priest Jave Wu as “the three Immortal Maidens of Singapore”.6

The Legends of Maiden Lim, the Mysteries of Maiden Lei

Hidden in the neighbourhood of Bukit Merah, between Gan Eng Seng Primary School and a forest of condemned seven-storey SIT (Singapore Improvement Trust) flats, you will find the dragon arch of Zhen Long Gong (Chin Leng Keng; 真龙宫).7 Remove your shoes and ascend the steps to the main hall, still gleaming from its 2022 renovations. Here, you will find the faithful paying their respects to dozens of Taoist and Mahayana Buddhist divinities: the bodhisattva Guanyin (Goddess of Mercy; 观音), the god of war Guan Gong (关公), the monkey king Sun Wukong (孙悟空), the medicine deity Baosheng Dadi (保生大帝), the god of grains Wugu Dadi (五谷大帝), and the tiger spirit Huye (虎爷), to name a few.

Here, worshippers also bow before Lin Guniang. Her statue is swaddled in a glittering multicoloured cape, fastened around her throat with a red ribbon. Beneath the fabric, she is garlanded with beads. Ritual offerings lie on her altar: boxed cosmetics, lipsticks and perfumes. Paper lanterns hang outside the temple doors, marked with her name. Each year, on the 15th day of the seventh lunar month, a small festival is held in her honour.

Some controversy surrounds her origins. The temple’s caretaker, 74-year-old Huang Yahong (黄亚宏), is happy to share what he knows of her legend, but cautions that certain details may only be shared orally, not in writing.8 It feels safe, nevertheless, to reveal that his account corresponds closely with one printed in the Straits Times in 1989.

She “lived around the turn of the century [c. 1900] and was married to a sailor who was frequently at sea. A neighbour by the surname of Tan tried to seduce her, but she spurned him. Furious, he framed her for infidelity. She committed suicide to prove her chastity and her spirit kept returning to help needy neighbours. Soon a shrine was erected for her in the Henderson Road area. As the story goes, she helps anybody except those with the surname of Tan”.9

The caretaker also reveals the fate of Tan, the neighbour whose gossip caused her death. Supposedly, he went mad and killed himself by driving a nail into his own head.

The most widespread version of the goddess’s tale, however, comes from television. In 1998, the Singapore Broadcasting Corporation (now Mediacorp) produced and aired the series Myths and Legends of Singapore (石叻坡传说), with the first episode titled “Lady of the Hill” (红山林姑娘), starring Fann Wong as Lin Guniang. It is this adaptation that currently serves as the primary reference for the goddess in online resources, such as Ronni Pinsler’s entry on his website, “The Book of Xianshen”,10 and Jave Wu’s blog, “International LSM Taoist Cultural Collegium”.11

In this retelling, Lin Guniang is depicted as living in the early to mid-19th century, dressed in a changshan (长衫). She is a practitioner of traditional Chinese medicine, while her jealously possessive husband, Ah Guang, is a hunter. When he accuses her of adultery, she jumps into a well, which then overflows with blood. After her death, her village is struck by a plague, but she returns as a spirit to aid the afflicted.

The writers of “Lady of the Hill” draw an explicit parallel between their tale and the Malay legend of how Redhill got its name. The episode opens with a representative of the National Museum of Singapore conducting research at Zhen Long Gong. When asked why the soil in the area is red, the worshippers repeat the familiar story of how the boy hero Hang Nadim was assassinated by an evil Raja, thus marking the earth with his blood. One worshipper then offers Lin Guniang’s tale as a counter-narrative, declaring, “It was her blood that stained the hill red.”

Huang the caretaker rejects this account. He reminds us that Lin Guniang’s shrine had its origins in Kampong Henderson, near Tiong Bahru, and not Bukit Merah. Any association between the shedding of her blood and the crimson earth would only have been invented after her shrine’s relocation.

He adds that her death could not have taken place more than a hundred years ago, as he is acquainted with a neighbourhood resident who was a little girl when the tragedy took place. Nor is the goddess particularly renowned for her healing powers.12 She bestows more general blessings upon her followers, though they were often known to ask her for luck in gambling, specifically in the popular lottery game of chap ji kee.13

But there is another, more recent story connected with the goddess, one that suggests my father had good reason to fear her power. This took place in the 1970s, shortly after Lin Guniang’s shrine on Henderson Road was cleared for redevelopment.

At the time, the Member of Parliament for Bukit Merah was Lim Guan Hoo. On Sunday, 13 February 1977, he collapsed from a stroke while attending an event at the National Stadium.14 He passed away on 3 August at the Singapore General Hospital (SGH) after being in a coma for 172 days.15

This was only one of many uncanny events that followed in the wake of the shrine’s demolition and subsequent relocation. “Among the Housing Development Board [HDB] people, many fell sick,” the caretaker says. “They were scared. The head of HDB was scared too. And one of our grassroots leaders, his son also died.”16

Then, around 1980, grassroots leader Yeo Chin Hua (杨振华) arranged to have Lin Guniang transported to Zhen Long Gong, an institution he had helped form by uniting four Taoist temples affected by redevelopment.17 According to his son, the goddess had visited him in a dream, expressing her wish to make her new home in this united temple.

The temple committee was happy to comply. But where would they house the goddess? She was technically a terrestrial spirit, distinct from the celestial gods, and might require a separate shrine on the temple grounds.

A solution came from Baosheng Dadi, the patron deity of Zhen Ren Gong (Chin Lin Keng; 真人宫), one of Zhen Long Gong’s constituent temples. During a ceremony, his statue was placed on a palanquin, and his spirit possessed his palanquin bearers, enabling them to trace a divine message in a heap of ashes. In writing, he granted Lin Guniang permission to be worshipped within his temple. The very same palanquin was later used to transport her statue to Zhen Long Gong.

Before we move on, return your gaze to the altar. To the right of Lin Guniang is the statue of yet another Singaporean folk goddess, named Lei Niangniang (Lui Niu Niu; 雷娘娘), or Maiden Lei. She, too, is honoured with her name on the temple’s paper lanterns, and a copper brazier is marked with the names of both goddesses, indicating their equal status. Below her stands a gift from a devotee: a framed rectangle piece of cloth, embroidered with her name and the date of her festival: the seventh day of the fourth lunar month.

What are her origins? Some call her Si Jiao Ting Lei Guniang (四脚亭雷姑娘), which suggests a connection with the Si Jiao Ting Hokkien Cemetery in Tiong Bahru.18 Huang the caretaker, on the other hand, insists she was native to Kampong Henderson, and that she was admitted to Zhen Ren Gong sometime in the 1950s.

“Her story is not known,” he says. “After her death, her spirit was felt in the village.” To pacify her soul, the temple deified her and bestowed her with her current title. Unfortunately, her mortal name, like her mortal deeds, is lost to history.

The Martyrdoms of Maiden Huang

A half-hour stroll from Zhen Long Gong brings us to Wat Ananda Metyarama on Jalan Bukit Merah, the oldest Thai Buddhist temple in Singapore. Saffron-robed monks perform chores amid common iconography in Theravada Buddhist temples: four-faced Brahma, the eclipse-causing deity Rahu, even a vibrant mural of the wheel of samsara in which appear the distinctive towers of Marina Bay Sands. Ignore these for now and enter the Julamanee Prasat: the small columbarium at the base of the temple’s three-storey belltower.

Here, you will find the tablet of Huang Guniang (黄姑娘), also called Maiden Huang, Maiden Ng and Ng Kor Niu. Her name is written in gold on red, couched on a stylised lotus and framed by flowering vines. In a glass cabinet, she sits on the topmost shelf, above 28 tablets of other deceased souls, while the ash-filled urns of other mortals occupy the walls of the neighbouring rooms.

The details of Huang Guniang’s legend are unusually precise. On his website, the Taoist priest Jave Wu states that she was born in 1866, on the 12th day of the sixth lunar month, in the village of Gu Ah Sua (龟仔山), later known as Kampong Silat. Her name was Huang Su Ying (黃素英, pronounced Ng Shor Eng in Hokkien and Wong Sok Eng in Cantonese). As her family was poor, she worked with her mother as a laundress from a young age.19

In 1879, Huang Guniang began doing laundry with her paternal aunt at the Kandang Kerbau Hospital. In 1882, they moved to SGH, which had just shifted to its current location on Outram Road. One day, a doctor suggested that she train to be a nurse. She qualified in 1900 and began caring for patients and assisting in the pharmacy.20

Sadly, death came for her the very next year, just before the Qingming Festival. A fire broke out one night at a kampong near her home. “Maiden Ng did not hesitate to volunteer herself at the fire site to assist the injured,” Wu says. “With a dash, she ran to the fire site… trying her best to save as many villagers as possible.” However, while attempting to rescue an old lady, the house she was in collapsed. Her body was never recovered.21

There are, of course, other accounts of her origins. In 2017, a then-66-year-old former resident of her kampong named Liu Xing Fa (刘星发) told Shin Min Ri Bao (新民日报) that Huang Guniang had killed herself for love after her family had matchmade her to someone else.22

As a child, Liu had witnessed the worship of Huang Guniang in Heng San Teng (恒山亭) on Jalan Bukit Merah. “She committed suicide near the temple,” he explained. “The kampong people couldn’t bear to let her become a wandering spirit, so they invited her into the temple to worship her.”23

Heng San Teng burned down in 1992. Around this time, a small shrine dedicated to the goddess was erected beneath a tree on Hospital Drive, within the SGH compound. It was a humble affair, consisting of a simple, red boxed altar where devotees had placed offerings of joss sticks, food and cosmetics before her tablet. Nevertheless, patients flocked to the site, desperately praying to her for good health.

“If on that very night after the honouring, the patient dream[s] of a big white spider or [a] spider with long legs, the chances of getting his illness cured will be high,” Wu notes. He adds that her presence brought an end to traffic accidents along Hospital Drive and the opposite road, and that visitors would occasionally catch a glimpse of her spirit at the junction near her shrine and her former temple.24

Alas, all this good work could not save Huang Guniang’s altar. In 2017, because of SGH’s plans for redevelopment and expansion, her shrine was cleared from its original site.25 According to Victor Yue, creator of the “Story of Ng Kor Niu 黄姑娘” Facebook group, the contractor engaged a Taoist priest to administer the shift.26 A huge paper mansion was also burnt for her as part of a ceremony to invite her to Wat Ananda Metyarama.

Worshippers continue to pray to the goddess at the columbarium. A small sign reading “This Way to Maiden Huang” has been posted by the front door, directing them to her tablet: a newer, more ornate piece than the one that formerly occupied her demolished shrine.

Some may grumble that SGH should have found her a home on their premises where she could continue to offer comfort to those in need of hope and healing. Yet there have been no whispers of vengeance in the five years following her move. Huang Guniang, it seems, is content.

Singapore’s Spirits

This essay is by no means a comprehensive survey of Singapore’s homegrown Taoist pantheon. Perhaps in future essays, we may make the acquaintance of other local gods and goddesses, such as Liang Taiye (梁太爷), Zhu Guniang (朱姑娘), Liu Xiu Guniang (刘秀姑娘), Cai Fu Xiao Guniang (蔡府小姑娘), Hong Hua Guniang (红花姑娘), Sun Jiang Jun (孙将军) and Zhang Fu Ren (张夫人). Some of these figures have long vanished from altars, while others still hold sway in temples. Some may still be honoured in household shrines around Singapore.

So far, most of the research into these local gods and goddesses has been conducted by passionate amateurs such as Ronni Pinsler, Jave Wu and Victor Yue. More formal scholarship is needed, not only to record the names and stories of these deities, but also to better grasp their place in Southeast Asian culture. What sense can we make of the parallels between their veneration and Malay keramat (shrine) worship?27 What parallels can we draw with other gods of the regional Chinese diaspora, such as Tua Pek Kong (Da Bogong; 大伯公), with his origins in Penang?28

In saying this, I do not mean to downplay the contributions of non-academics in this field. On platforms such as the “Local Gods & Their Legends” and “Taoism Singapore” Facebook groups, aficionados share knowledge about ritual practices across the region.29 Here, we share recollections of forgotten deities and learn about those still worshipped in our midst. Regardless of whether we are believers, sceptics or just agnostic, we work to keep our sacred heritage alive.

Lin Guniang, Lei Niangniang and Huang Guniang have not, in my opinion, been accorded the full respect they deserve. Over the decades, their congregations have dwindled, their shrines have been destroyed and their tales have been carelessly rewritten.

Nevertheless, their existence remains an inspiration. They serve as proof that Singapore is not merely a meeting place for spiritual cultures, but a site for their creation. This is not a disenchanted island. This is a city where goddesses are born.

Ng Yi-Sheng is a poet, fictionist, playwright and researcher. His books include the debut poetry collection last boy, A Book of Hims and Loud Poems for a Very Obliging Audience, and the short story collection Lion City, which won the Singapore Literature Prize in 2020. He tweets and Instagrams at @yishkabob.

Ng Yi-Sheng is a poet, fictionist, playwright and researcher. His books include the debut poetry collection last boy, A Book of Hims and Loud Poems for a Very Obliging Audience, and the short story collection Lion City, which won the Singapore Literature Prize in 2020. He tweets and Instagrams at @yishkabob.NOTES

-

Singapore’s Lin Guniang must not be confused with the goddess Lin Guniang (or Lim Ko Niao) worshipped in southern Thailand. The two are distinct and unrelated deities, and the term “guniang” simply means girl or young woman in Mandarin. For more information, see Mistuko Tamaki, “The Prevalence of the Worship of Goddess Lin Guniang by the Ethnic Chinese in Southern Thailand” (G-SEC Working Paper 22, Keio University Global Research Institute (KGRI), December 2007), https://www.kgri.keio.ac.jp/en/docs/GWP_22.pdf. ↩

-

Ng Hark Seng, interview, 26 July 2022. ↩

-

William L. Gibson, “Unravelling the Mystery of Ubin’s German Girl Shrine,” BiblioAsia 13, no. 3 (Oct–Dec 2021). ↩

-

Ronni Pinsler, “Local Gods & Their Legends,” Facebook, accessed 27 September 2022, https://www.facebook.com/groups/localgods/posts/. ↩

-

Ronni Pinsler, “The Book of Xian Shen,” accessed 15 September 2022, https://bookofxianshen.com/. ↩

-

Jave Wu, “Story of Maiden Lim of Redhill (石叻坡傳奇之紅山林姑娘),” International LSM Taoist Cultural Collegium, 1 March 2013, http://javewutaoismplace.blogspot.com/2013/03/story-of-maiden-lim-of-redhill.html. ↩

-

Zhen Long Gong (Chin Leng Keng) is made up of four temples: Leng San Teng, Chin Lin Keng, Kai Kok Tien and Ban Sian Beo. The four temples were affected by urban redevelopment in the early 1970s. They came together in 1976 to lease the current site for the construction of Zhen Long Gong, which was completed in 1978. ↩

-

Huang Ya Hong, interview, Zhen Long Gong, 20 June 2022. ↩

-

“Singapore Maiden Joins the Taoist Pantheon,” Straits Times, 27 May 1989, 22. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Pinsler, “Book of Xian Shen.” ↩

-

Wu, “Story of Maiden Lim.” ↩

-

There is in fact some evidence for Lin Guniang’s reputation as a healer. According to historian Tai Wei Lim, elderly taxi drivers in the neighbourhood agree that she “has special Shamanistic healing powers and even [helps] out at traditional Chinese medicine institutions”. Is this entirely based on the 1998 TV serial, or are they citing deeper memories? See Lim Tai-Wei, Cultural Heritage and Peripheral Spaces in Singapore (Singapore: Palgrave Macmillian, 2017), 68. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 363.69095957 LIM) ↩

-

Still other variations of Lin Guniang’s origin myth exist. My mother, for instance, says her own mother shared a version in which Lin Guniang was the victim of sexual violence. Ng Gim Choo, interview, 26 July 2022. ↩

-

“Lim Still On Danger List,” New Nation, 15 February 1977, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“MP Dies,” New Nation, 3 August 1977, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

According to Huang Yahong, shortly before Lin Guniang’s shrine was removed, a small Hindu shrine in the same area was also demolished. Worshippers at Zhen Long Gong associate this incident with the sudden death of MP for Radin Mas N. Govindasamy on 14 February 1977, just a few hours after Lim’s collapse. See “MP Dies.” ↩

-

Yeo Keng Hoo (son of Yeo Chin Hua), interview, Zhen Long Gong, 22 August 2022. ↩

-

Wu, “Story of Maiden Lim.” ↩

-

Jave Wu, “Introduction on Nanyang Huang Gu Niang (南洋龜仔山黃姑娘簡介),” International LSM Taoist Cultural Collegium, 10 July 2012, http://javewutaoismplace.blogspot.com/2012/07/introduction-on-nanyang-huang-gu-niang_4039.html. ↩

-

Wu, “Introduction on Nanyang Huang Gu Niang.” ↩

-

Wu, “Introduction on Nanyang Huang Gu Niang.” ↩

-

Xiao Jiahui 萧佳慧 and Pan Wanli潘万莉, “Sheishi Huang Guniang? Jumin jiemituan,” 谁是黄姑娘? 居民揭谜团 [Who is Miss Huang? Residents reveal the mystery], Xinmin Ribao 新民日报, 7 September 2017, 4. ↩

-

萧佳慧 and 潘万莉, 谁是黄姑娘? 居民揭谜团 [Who is Miss Huang? Residents reveal the mystery]. ↩

-

Wu, “Introduction on Nanyang Huang Gu Niang.” ↩

-

Melody Zaccheus, “Old Graves, Shrine to Make Way for SGH Redevelopment,” Straits Times, 6 September 2017, https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/environment/old-graves-shrine-to-make-way-for-sgh-redevelopment. ↩

-

Victor Yue, Facebook direct message, 30 July 2022. ↩

-

Such analysis, I believe, is more important than determining the factuality of legends. Though I have spoken of the three goddesses as if they are historical figures, I have uncovered no concrete evidence of their lives as mortal women. It is, I concede, entirely possible that they never walked the earth. If true, this does not diminish their power. As goddesses, they operate on a spiritual plane that transcends human logic. ↩

-

Jack Chia Meng-Tat, “Who Is Tua Pek Kong? The Cult of Grand Uncle in Malaysia and Singapore,” Archiv Orientalni 85, no. 3 (2017): 439–60, 490. https://aror.orient.cas.cz/index.php/ArOr/article/view/154. ↩

-

“Taoism Singapore,” Facebook, accessed 27 September 2022, https://www.facebook.com/groups/taoismsingapore. ↩