Stories from the Stacks

The National Library’s newest exhibition, “From the Stacks”, presents highlights of its Rare Materials Collection. Chung Sang Hong explains why you should not miss this event.

The noun “stack” usually refers to a pile of objects, such as “a stack of books”. It also means, by extension, a large quantity of something, as in the idiom “needle in a haystack”. In digital language, “stacks” can refer to computer memory storage. However, in libraryspeak, “stacks” are shelving units in a section of a library that is usually closed to the public.1 In most libraries, the less frequently consulted publications are usually kept in “closed stacks”.

The exhibition “From the Stacks: Highlights of the National Library” – which takes place from 30 January to 28 August 2016 at Level 10 of the National Library Building – presents over 100 items largely drawn from the library’s Rare Materials Collection. Given the size of the library’s 11,000-item strong collection, the exhibition provides only a snapshot of what its archives contain. But it is nonetheless a snapshot that presents a broad spectrum of materials across various subjects.

On display are publications, manuscripts, maps, documents and photographs from the early 18th century to more recent times, which taken as a whole, represent a small but significant part of Singapore’s published heritage. Together, these items piece together a fascinating mosaic of Singapore’s history and its socio-political developments, and present stories about people, communities and vignettes of life in times past.

The First School and Library

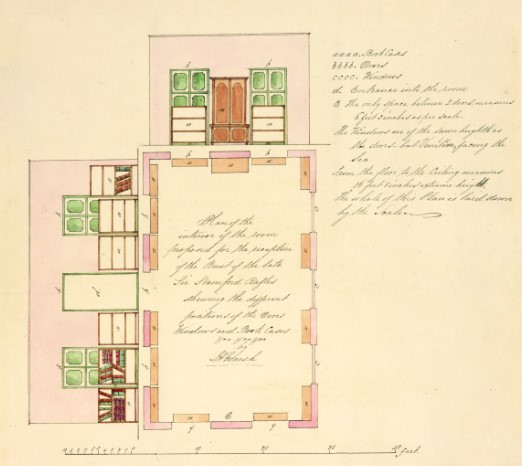

As stories go, we must start from the beginning: the exhibition first traces the origins of the National Library, which is closely linked to the formation of the first school, the Singapore Institution – better known today as Raffles Institution.

Stamford Raffles envisioned Singapore as a commercial hub and a centre for learning and culture. Shortly after its founding in 1819, he drafted a proposal for the establishment of an institution of higher learning that would include a library and publishing function. One of the institution’s objectives was:

“To collect the scattered literature and traditions of the country, with whatever may illustrate their laws and customs, and to publish and circulate in a correct form the most important of these… to raise the character of the institution and to be useful or instructive to the people.”2

The proposal was not acted upon until 1823 when Raffles convened a meeting to establish the Singapore Institution. At the recommendation of the missionary Robert Morrison, plans for a library, museum and printing press were included in the formation of the institution.3 However, its opening was delayed again for various reasons and deviated from Raffles’ original intent. Eventually, when the Singapore Free School moved into the building that was meant for the Singapore Institution at Bras Basah Road in 1837, it housed a small library that was available for public use for a small fee.

In response to appeals from residents for a proper public library that could be accessed beyond school hours, the Singapore Library eventually opened on 22 January 1845 on the premises of the Singapore Institution. The library, however, could only be used by paid subscribers. Such were the humble beginnings of the first school and library in Singapore.

The First Printing Press

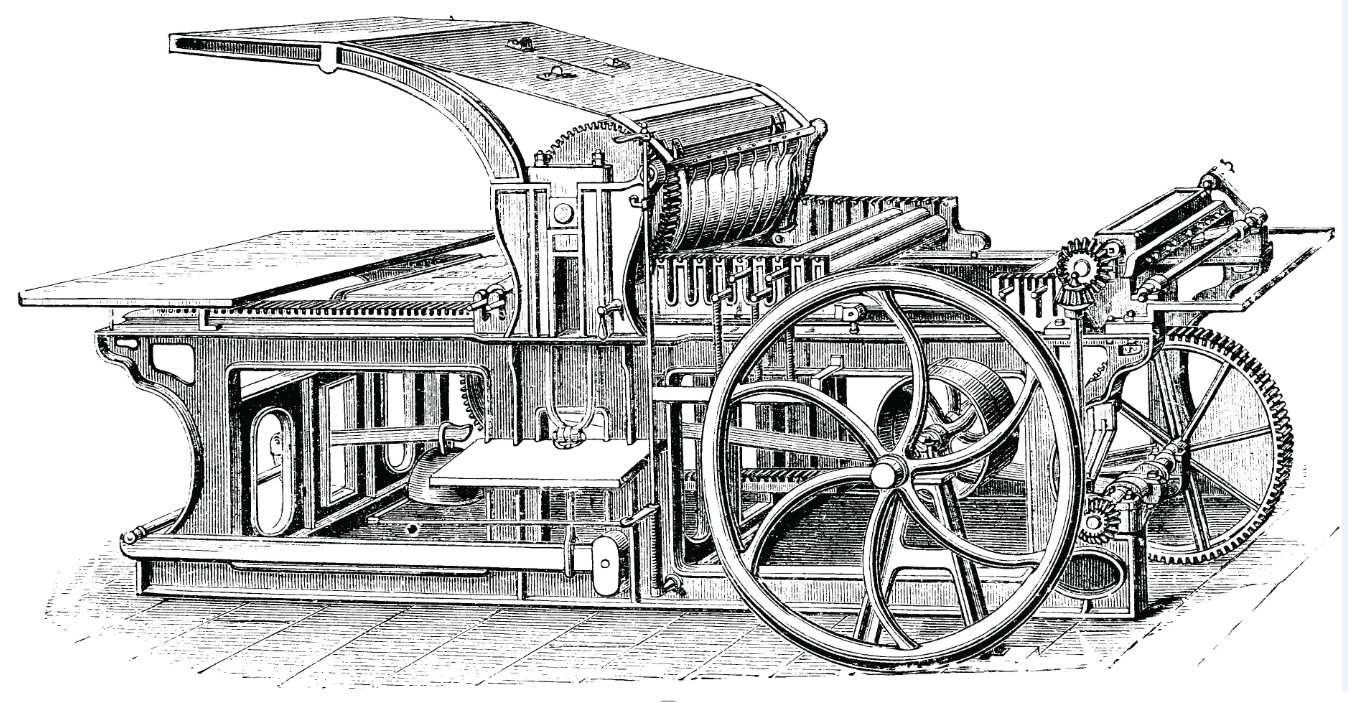

Several items in the exhibition are rare editions of the earliest publications printed in Singapore. Interestingly, Singapore’s publishing history is closely intertwined with the proselytising activities of early Christian missionaries in the region. The earliest English, Chinese and Malay titles in the National Library are all outputs of printing presses in Singapore that were run by Protestant missions in the early years of the 19th century.

Christian missionaries followed the footsteps of Raffles and started work in Singapore soon after it was founded. The Reverend Samuel Milton of the London Missionary Society (LMS) came to Singapore from Malacca in October 1819 to start a station on the island. In 1822, fellow missionary Claudius Henry Thomsen arrived in Singapore and brought with him a printing press and a few workers. The following year, the first printing press in Singapore, the Mission Press, came into operation.4 Thomsen learnt Malay from the accomplished Muslim scholar, Abdullah bin Abdul Kadir (better known as Munshi Abdullah) and collaborated with the latter in the translation and publication of Christian gospels and literature into Malay.5

The printing and distribution of Christian literature was a major part of missionary work, besides preaching and establishing schools. Religious scripture, tracts, periodicals and fiction were published in Malay and Chinese in order to proselytise to the local communities as well as to those in the surrounding regions. On display at the exhibition are two significant publications: a Malay translation of the Sermon on the Mount – based on the Gospel of Matthew – published in 1829, and a gospel tract in Chinese titled The Perfect Man’s Model (全人矩矱), written by the German missionary Karl Friedrich August Gützlaff and printed in 1836.

The Mission Press’s publishing output was prolific – close to one million copies of religious and secular publications in Chinese, Malay and other languages were printed in Penang, Malacca, Singapore and Batavia between 1815 and 1846.6 Southeast Asia, however, was just a pit stop en route to a much larger prize – the missionaries’ ultimate aim was to spread Christianity in China.

Before the First Opium War (1839–42), proselytising in China by foreign missionaries was prohibited. To get around this, Western missionaries set up bases in the British settlements in Southeast Asia to reach out to the large and growing Chinese migrant population as well as its indigenous people. Due to its strategic position at the tip of the Malay Peninsula, Singapore was a major port of call for the numerous vessels plying between China and Southeast Asia. Taking advantage of this, the missionaries actively distributed their publications to the Chinese on board these ships, with the hope that the literature would eventually find its way into China and be disseminated among the people.7

Some of the publications printed in Singapore and Malacca would be the first encounters of Western ideas and knowledge for the people of China. The Mission Press also undertook the printing of secular works, including government gazettes, the first local newspaper, the Singapore Chronicle in 1824, and the Hikayat Abdullah by Munshi Abdullah in 1849, one of the most important works of Malay literature and an important source of early Singapore history. Both publications are on display at the exhibition.

When China was forced to open its doors to foreigners after the Opium War, many missionaries in Southeast Asia shifted their base to China, leaving behind a legacy of publications that had been printed in the region. The history of publishing in Singapore owes a clear debt of gratitude to the work of these pioneering Christian missionaries.

However, publishing in Singapore was by no means the monopoly of the Protestant missionaries. In the later part of the 19th century, other printing presses were established. The first locally printed Tamil publication in the National Library is a collection of Islamic devotional poems titled Munajathu Thirattu, dated 1872. It was written by Muhammad Abdul Kadir Pulavar, a pioneer Indian Muslim poet and publisher of the earliest known Tamil newspaper in Singapore, Singai Vardhamani or Singapore Commercial News. The Indian Muslim community, which owned several printing presses, came to dominate the publishing of Tamil and Malay newspapers in Singapore.

One of the oldest Chinese printing presses in Singapore was Koh Yew Hean Press (古友轩), founded by Lin Hengnan (林衡南) in the 1860s at Telok Ayer Street. Lin came to Singapore in 1861 and became fascinated with the lithographic technology of the British.8 He picked up the trade within a short time and set up his own printing press. Koh Yew Hean Press published the first Chinese-Malay dictionary in Singapore, Hua yi tong yu (华夷通语) in 1883 (see page 88), as well as other publications in other languages, such as a Jawi version of the Hikayat Abdullah (1880), and the first four issues of the English-language Straits Chinese Magazine (1897).9

Loyalties and Identities in Transition

Also included in the exhibition are artefacts that provide important clues to the political affiliations and cultural affinities of various communities in Singapore. One of the most elaborate items is a double-fold fuschia-coloured silk manuscript titled “Address to Alfred, Duke of Edinburgh by the Singapore Chinese Merchants on the Occasion of His Visit to Singapore in 1869”. The handwritten manuscript, flanked by carved wooden covers and featuring a panorama of Singapore painted on the reverse, expresses the Chinese merchants’ steadfast loyalty and gratitude to Queen Victoria and British rule. The Loyalty Address bears the signatures of prominent Chinese merchants such as Tan Kim Ching, Chiang Hong Lim, Seah Eu Chin and Hoo Ah Kay.

Many Chinese in the upper crust of colonial society were Peranakan (Straits-born Chinese), who were educated in English and embraced the culture of the British. By the late 19th century, however, social and political changes in China revived their interest in Chinese culture and affairs.

One manifestation of this was The Straits Chinese Magazine, published between 1897 and 1907 by two well-known Peranakan personalities, Lim Boon Keng and Song Ong Siang, a doctor and lawyer respectively. The magazine featured articles on wide-ranging topics that concerned the Peranakan as well as other communities. It advocated social, political and cultural reforms for the Chinese – warning of the ills ofopium, championing education for Chinese girls and calling for Chinese men to cut their queues, or pigtails. As the first English periodical published by locals, the magazine presented a unified Malayan voice and explored what it meant to be Chinese in the British colony.10

There are too many publications of note in the exhibition to be highlighted in this article. Most are outlined in detail in this issue of BiblioAsia. The earliest item on display in the exhibition is the first ever English-Malay dictionary published in 1701 and the most recent is the first cookbook by a Singaporean author, Ellice Handy’s My Favourite Recipes (revised edition, 1960).

The exhibits cover a wide array of topics, from politics, history, sociology, language and religion to current affairs, nature, travel, food and more. Some of the more novel items on display include a rare 1901 photo album by G. R. Lambert & Co. containing faded images of old Singapore, a colonial cookbook of “420 tried and economical recipes” published in 1920 for British housewives struggling to run their households in Malaya, and what is probably the first travel guidebook of Singapore, published in 1892.

Look out also for the collection of delightful English nursery rhymes translated into Malay (1939); probably the first Qu’ran printed in Singapore in 1869; a Baba Malay translation of the Chinese classic Romance of the Three Kingdoms; and a series of chilling cartoons on Japanese brutality and torture, going by the unlikely name of Chop Suey (1946).

Chung Sang Hong is Assistant Director, Exhibitions & Curation, with the National Library of Singapore. His responsibilities include project management and the curation of exhibitions.

Chung Sang Hong is Assistant Director, Exhibitions & Curation, with the National Library of Singapore. His responsibilities include project management and the curation of exhibitions.

NOTES

-

Oxford University Press. (2015). Stack. Retrieved from Oxford Dictionaries website. ↩

-

Raffles, T.S. (1819). Minute by Sir T. S. Raffles on the establishment of a Malay college at Singapore (p. 17). [S.l. : s.n.]. Retrieved from BookSG. ↩

-

Raffles, T. S. (1823). Formation of the Singapore Institution, A.D. 1823 (pp. 56–59). Malacca: Mission Press. Retrieved from BookSG. ↩

-

National Library Board. (2008). Mission Press written by Lim, Irene. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia. ↩

-

Hunt, R. A. (1989). The history of the translation of the bible into Bahasa Malaysia. Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 62 (1) (256), p. 38. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

Su, C. (1996). The printing presses of the London Missionary Society among the Chinese (p. 97). Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University College London. ↩

-

Singapore Christian Union. (1830). The first report of the Singapore Christian Union (pp. 10–11). Singapore: The Mission Press. Retrieved from BookSG. ↩

-

Beijing tu shu guan [北京图书馆]. (2000). Beijing tu shu guan cang jia pu cong kan. Min yue (qiao xiang) juan (北京图书馆藏家谱丛刊 – 闽粤(侨乡)卷) [Collection of genealogies in the Beijing Library – Fujian & Guangdong Provinces] (pp. 1, 423). [北京]: 北京图书馆出版社.(Call no.: Chinese RCO q929.10720512 BJT) ↩

-

Lu Shicong [吕世聪]. (2015, October 25). Guyouxuan, Bendi Zuizao Huaren Yinwuguan (古友轩 – 本地最早华人印务馆) [Koh Yew Hean Press – the oldest Chinese printing press in Singapore]. Lianhe Zaobao [联合早报], pp. 18–19. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Tan, B. (July 2011). The Straits Chinese Magazine: A Malayan Voice, BibioAsia,7 (2), 30–35. Retrieved from BiblioAsia website. ↩